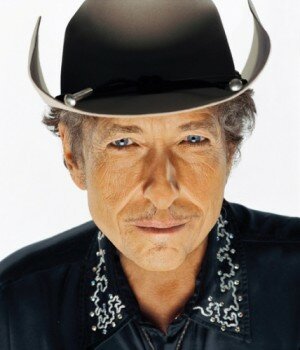

You Had To Ask Me Where It Was At: Bob Dylan & the Media

An exploration of Dylan’s media relations, as refracted through Rolling Stone’s anthology of ‘essential’ Dylan interviews and press conference transcripts.

by John Carvill

Part Two: Poets Drown in Lakes

What sort of cumulative impressions await the reader of a collection of Bob Dylan’s early interviews, magazine profiles, and press-conference transcripts? Well, it all depends on the granularity of your focus. Looking at the big picture, you cannot fail to be struck by their value as historical documents; and it’s hard to avoid feeling a certain amount of incredulity at just how out of touch the journalists were with the changing times they were meant to be reporting on. But there are also any number of minor revelations, one of which being that the degree to which Dylan could always be relied upon to be both evasive and aggressive, has been much exaggerated. In a New Yorker profile, Nat Hentoff manages to explode both sides of this myth in one short paragraph:

“Dylan came into the control room, smiling. Although he is fiercely accusatory toward society at large while his is performing, his most marked offstage characteristic is gentleness. He speaks swiftly but softly, and appears persistently anxious to make himself clear.”

Even when Dylan does lash out, any hostility is almost always leavened with his unique brand of wit. At the KQED press conference, in response to reporters’ attempts to ascribe a ‘meaning’ or a ‘message’ to Dylan’s lyrics, Dylan points out that words can have different meanings and that these are subjective. Why then, someone asks, does Dylan bother to write at all:

Q. “What do you bother to write the poetry for if we all get different images? If we don’t know what you’re talking about?”

A. “Because I’ve got nothing else to do, man!”

Both the question itself, and the way it’s delivered, are quite confrontational; but even though Dylan’s reply seems correspondingly antagonistic, the tone is still good-humoured, even self-deprecating. Perhaps sensing that Dylan doesn’t want to discuss what he is ‘saying’ in his songs, Ralph Gleason himself invites Dylan to comment on what he’d like to say that isn’t in his songs:

Gleason: Is there anything in addition to your songs, that you want to say to people?

Dylan: Good luck.

Gleason: You don’t say that in your songs anywhere, do you?

Dylan: Oh yes I do. Every song tails off with: good luck. I hope you make it.

Dylan’s lyrics, says Nat Hentoff, are “pungently idiomatic”; the same could be said of Dylan’s sense of humour. One of many striking facets of Dylan’s conversational style, which an anthology of interviews makes more readily apparent than ever, is his propensity for dispensing memorable aphorisms and apercus. He tells Hentoff that, “the word ‘message’ strikes me as having a hernia-like sound”, while “the word ‘protest’, I think, was made up for people undergoing surgery”. In an interview with Mikal Gilmore from 1986, Dylan discusses the critical view that his career is in decline, rejecting the suggestion that he has anything to prove, or has to live up to his own past achievements: “Besides, anything you want to do for posterity’s sake, you can just sing into a tape recorder and give it to your mother, you know?”

In conversation, as in song-writing, Dylan has an uncanny knack for le mot juste. Sometimes he even seems to be pulling a freshly minted neologism out of his hat. “Anybody that gets into politics is”, he warns Paul J Robbins, of the LA Free Press, in 1965, “a little greaky anyway.” The structure of ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ was, he tells Robert Shelton, “very vomitific”. The less he likes the turn a conversation is taking, the more acute and idiosyncratic Dylan’s humour seems to become. During the Playboy interview, he bridles at the idea of himself being regarded as a role model:

“I’m really not the right person to tramp around the country saving souls. I wouldn’t run over anybody that was lying in the street, and I certainly wouldn’t become a hangman. I wouldn’t think twice about giving a starving man a cigarette. But I’m not a shepherd. And I’m not about to save anybody from fate, which I know nothing about.”

Who else would have used the verb ‘to tramp’ there? It makes him sound like something out of a Dostoevsky novel.

If Dylan the Interview Gorgon is a myth reporters like to frighten their children with at night, an equally prevalent one has long been the supposed rarity of a Dylan interview. Michael Gray estimated that Dylan has given an average of one interview per month for the whole of his career, and “since the mid-1960s almost every one is published prefaced by the claim that it comes from a man who rarely gives interviews.” As well as giving the reader who is aware of this a wry smile every time it crops up – and it does – this also highlights the fact that in compiling this collection, the editors had a lot of raw material to choose from.

Which is where this book starts to run into trouble. In 2007, Columbia’s release of the latest, and most superfluous, in a long line of Dylan ‘best of’ collections – a 3 CD set thrillingly entitled ‘Dylan’ – provoked a chorus of well-deserved complaints, due to its unimaginative and unadventurous song selections. The problem is, Bob Dylan is an artist of such incredible range and depth that he’s really a genre unto himself. His back catalogue is brimming with so many masterpieces, and his career has encompassed so many phases, that he simply cannot be boiled down to one homogenous overview. If you’re putting together a Dylan compilation, there are dozens of songs that you cannot realistically opt to exclude; but the more of them you do include, the less space you have left to play with. It’s yet another indication of Dylan’s uniqueness that the same applies to his interviews, on a couple of levels. First off, there’re a lot of them to choose from; more problematically, many of the best ones will already be quite familiar to the core constituency of the book’s potential readership.

Jonathan Cott cites Virginia Woolf’s comment in ‘Orlando’ that “a biography is considered complete if it merely accounts for six or seven selves, whereas a person may well have as many thousand.” In Dylan’s case, it’s possible to identify a number of ways of categorising those teeming shoals of multifarious selves. One obvious distinction is between those ‘Dylans’ which are mere manifestations of one or other of Dylan’s ‘sides’ asserting itself (and are therefore in a state of almost perpetual flux), and those which are anchored in reasonably well-defined chronological segments of Dylan’s career. (This latter category includes the ‘Dylans’ depicted in Todd Haynes’s aptly titled film, ‘I’m Not There’, in which seven ‘Bob Dylans’ are played by a total of six actors.) If we drill down a bit further into this DNA of the Dylan mythology, we recognise that in terms of their respective impacts upon the pop-cultural gestalt, the subset of (historical) Dylans which roamed the Earth during the 1960s must be considered the most ‘essential’. So it’s natural for any anthology to give over a significant amount of space to what we might call the ‘canonical’ Dylan interviews; but there’s always a danger that in so doing, the compiler leaves himself little room for more left-field inclusions.

Another problem lies in the fact that it would not be hard to take the contrary view, i.e. to argue that as the decades rolled by, and Dylan’s critical and commercial clout declined, he actually became more, rather than less, interesting. In fact, once you start thinking in these terms, such an assertion begins to look irrefutable, if only because beneath the surface contours of each successive Dylan lies the palimpsest of all the preceding Dylans. In which case, this collection is balanced, to a large extent, in the wrong direction: of the 31 total pieces, twelve are from the 60′s, six from the 70′s, seven from the 80′s, four from the 90′s, and only two from this Millennium.

Dylan spent much of the Eighties and Nineties wandering in a sort of critical wilderness. The origins of this phenomenon are sufficiently complex and amorphous to defy any attempt at fixing a date to the moment the downward slide began. But any even halfway serious consideration of Dylan’s lost forgotten years would have to start with the trifecta of artistic and commercial disasters Dylan inflicted upon himself – and his audience – during the 1980s: (1) allowing his (frequently half-hearted) songs to be basted in a thick, gloopy syrup of instantly-dated Eighties production values; (2) embalming his heretofore incomparably fecund and unfettered imaginative artistry in po-faced, hair-shirted fundamentalist ‘Born Again’ Christianity; and (3) the gruesome spectacle of his anticlimactic on-stage implosion, in the drunken company of Rolling Stones Ron Wood and Keith Richards, in front of a worldwide TV audience numbering in the billions, at Live Aid in 1984.

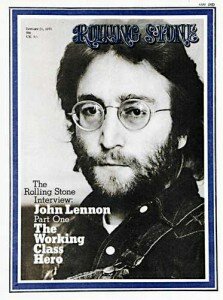

If Dylan’s music became decidedly patchy during the 80’s, Dylan as a person was just as potentially interesting an interviewee as ever, if not more so, not just because he had instant access to all those still-fascinating earlier Dylans, but because of the particular nature of the volatile dynamic between Dylan and the media at the time. On one hand, certain segments of the media had changed since Dylan’s first encounters with the press in the early Sixties; or, rather, new segments had emerged which were (or aimed to be) more simpatico with Dylan – Rolling Stone magazine being a prime example. But when these people came to interview Dylan in the Eighties, they were shocked to discover that their musical, cultural, and political sensibilities – which Dylan had had a significant hand in forming – were jarringly incompatible with Dylan’s current worldview.

The ‘Dylan finds Jesus’ thing was not the whole story, by any means, but it was certainly at the heart of this problem. At the same time, given Dylan’s new-found, old-time religious fervour, and (what seemed to be) his concomitant swerve to the right politically, he might have seemed to be perfectly in synch with a decade in which America’s religious Right were very much in the ascendant. But anyone wanting to claim Dylan for their reactionary cause would have stood to have their hopes just as comprehensively dashed as those who expected him to still be flying the Sixties freak flag. What tied these two contradictory strands together – aside from the fact that neither latter-day hippie nor Reaganite Christer could count on Dylan’s support – was that once again Dylan found himself in the position of confounding all sides in a politically charged time, resenting and instinctively rejecting the idea that he might be taken as representative of, or even in tune with, the times.

The resultant misunderstandings and conflicts make for fascinating reading, and it’s a shame that so many Eighties interviews are conspicuously absent from this book. No collection of Dylan interviews is complete, surely, without the wonderfully frank and acerbic interview (fragmented though it may be) that Dylan gave to Cameron Crowe, for the Biograph box set booklet in 1985. Highlights include: Dylan letting off steam (somewhat disingenuously) about people who analyse his songs – “stupid and misleading jerks sometimes these interpreters are”; slamming pop stars who sell out to commercial interests: “You know things go better with Coke because Aretha Franklin told you so” (yes, this would become supremely ironic later, but that’s another story); and expressing his disaffection with the tenor of the times by predicting that future generations would look back upon the 1980s as “the decade of masturbation”. Most poignantly of all, he fulminates at length about the tendency of big business and the media to glom onto anything authentic or subversive, such as Rock ‘n’ Roll, in order to sanitise and neutralise it, to “choke-hold it and reduce it to silliness”:

“It’s like Lyndon Johnson saying ‘We shall overcome’ to a nation-wide audience, ridiculous… there’s an old saying, ‘If you want to defeat your enemy, sing his song’ and that’s pretty much still true.”

Was it a copyright issue, or just unfriendly rivalry, that excluded the fascinating interview Dylan did with ‘Spin’ magazine in 1985? Dylan treated Spin’s Scott Cohen to an amazing demonstration of his never-faltering ability to walk the finest of lines between sophistry and candour, between down-home folk wisdom and spaced-out kookiness, bemoaning media myths whilst simultaneously stoking their fires:

“A lot of people from the press want to talk to me, but they never do, and for some reason there’s this great mystery, if that’s what it is. They put it on me. It sells newspapers, I guess. News is a business. It really has nothing to do with me personally, so I really don’t keep up with it. When I think of mystery, I don’t think about myself. I think of the universe, like why does the moon rise when the sun falls? Caterpillars turn into butterflies? I really haven’t remained a recluse. I just haven’t talked to the press over the years because I’ve had to deal with personal things and usually they take priority over talking about myself. I stay out of sight if I can. Dealing with my own life takes priority over other people dealing with my life. I mean, for instance, if I got to get the landlord to fix the plumbing, or get some guy to put up money for a movie, or if I just feel I’m being treated unfairly, then I need to deal with this by myself and not blab it all over to the newspapers. Other people knowing about things confuses the situation, and I’m not prepared for that. I don’t like to talk about myself. The things I have to say about such things as ghetto bosses, salvation and sin, lust, murderers going free, and children without hope–messianic kingdom-type stuff, that sort of thing–people don’t like to print. Usually I don’t have any answers to the questions they would print, anyway.”

He also added a helpful extra layer of confusion to the already ambiguous sense of identity in ‘I & I’:

“It’s up to you to figure out who’s who. A lot of times it’s “you” talking to “you.” The “I,” like in “I and I,” also changes. It could be I, or it could be the “I” who created me. And also, it could be another person who’s saying “I.” When I say “I” right now, I don’t know who I’m talking about.”

And what’s with the blanket ban on anything from a little continent called ‘Europe’? (A note to pedants: no, a short telephone interview for ‘Guitar World’, reprinted in ‘Uncut’ magazine, doesn’t really count.) This anthology is unquestionably the poorer for omitting the fractious 1986 ‘Hearts of Fire’ Press Conference in London, where Dylan repeatedly skewers the unpleasantly relentless Philip Norman:

PN: Are you easily bored, Mr Dylan?

BD: I’m never bored!

PN: Have you any notion of how bored you’re gonna be doing this picture?

BD: Well… [grimace]… maybe you’ll be around.

To omit the ‘Hearts of Fire’ press conference may be regarded as a misfortune, but to ignore the associated BBC documentary, ‘Getting to Dylan’, begins to look like carelessness. Dylan unnerves the BBC’s interviewer, Christopher Sykes, by spending the entire meeting working on a pencil sketch of him – a perfect metaphor for the way Dylan is so determined to turn the interview dynamic on its head.

“Well, y’know, I’m not gonna say anything that you’re gonna get any revelations about…It’s not gonna happen,” he warns Sykes. But then he goes on to deliver a nifty little homily about his celebrity preventing him from being able to walk into an ordinary situation, like a pub at night, without his presence radically altering, and therefore excluding him from, its essential ordinariness. And how about this nugget of classic Dylan:

Sykes: We all have our favourite rebels I guess.

Dylan: Yeah! That must be it!

Sykes: Who do you admire?

Dylan: Who is there to admire now? Some world leader? Who? I could probably think of many people actually that I admire. There’s a guy who works in a gas station in LA – old guy. I truly admire that guy.

Sykes: What’s he done?

Dylan: What’s he done? He helped me fix my carburettor once.

Special mention is due, also, to a Sunday Times piece from 1984, which describes the obstacle course journalists often have to negotiate in order to secure a Dylan interview: “Meeting him involves penetrating a frustrating maze of ‘perhapses’ and ‘maybes’, of cautions and briefings – suggestive of dealing with fine porcelain.” Of course, we notice that in all such cases the journalist does eventually get his interview, and either he realises this all along, in which case he is having his readers on, or he has himself fallen for yet another Dylan media myth, one which Dylan himself consciously uses that journalist to help perpetuate.

If the tone of the Sunday Times piece is ever so slightly snide, it doesn’t wholly detract from Dylan’s intrinsic charm and intelligence, or prevent him from throwing out an indelible sound bite. Here’s Dylan, looking back on the 1960s, “with something approaching affection”:

“I mean, the Kennedys were great-looking people, man, they had style,” he smiles. “America is not like that anymore. But what happened, happened so fast that people are still trying to figure it out. The TV media wasn’t so big then. It’s like the only thing people knew was what they knew; then suddenly people were being told what to think, how to behave, there’s too much information. It just got suffocated. Like Woodstock – that wasn’t about anything. It was just a whole new market for tie-died t-shirts. It was about clothes. All those people are in computers now.” This was beyond him. he had never been good with numbers, and had no desire to stare at a screen. “I don’t feel obliged to keep up with the times. I’m not going to be here that long anyway. So I keep up with these times, then I gotta keep up with the 90s. Jesus, who’s got time to keep up with the times?”

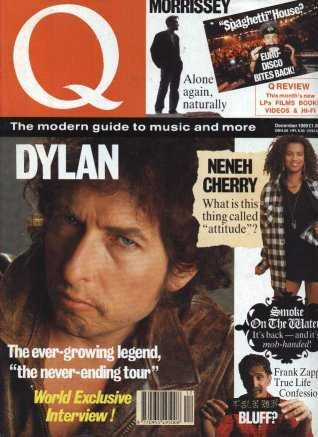

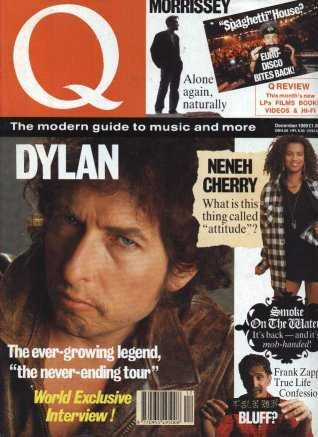

Another English article which laments the precarious process of securing an audience with Dylan, is his 1989 ‘Q’ magazine interview, notable for having given birth to the phrase ‘Never-Ending Tour’ (though whether this now universally accepted term was coined by Dylan, as suggested in the piece, or by the journalist, Adrian Deevoy, is still disputed). In the run-up to the repeatedly-delayed meeting, Dylan’s manager warns Deevoy that Dylan doesn’t like publicity:

“He hates it. Doesn’t need it. He just turned down the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. He said they should get someone off the street and interview them about Bob Dylan. That’d be more interesting. They said, Great idea, Bob, but that won’t sell any magazines. He said, Exactly. Why should I prostitute myself to sell magazines for you?”

It’s great stuff, and all the better when you realise that all these stern warnings about Dylan’s refusal to play the media game are being issued in the context of Dylan preparing to do a cover story for a magazine.

The story of Dylan’s gradual fall from critical grace, and his wholly unexpected resurrection, will one day make for a fascinating book in its own right, perhaps entitled ‘That’s How It Is, When Things Disintegrate’. Many fans experienced an understandable degree of disenchantment with Dylan during the 1980s. After all, he seemed to be cheerfully abandoning many of the facets which had made him Dylan in the first place. But the obvious relish the media took in declaring him an irrelevancy simply reflected their delight that Dylan, whom they had landed many a body blow upon, yet had never quite managed to knock out, had now seemingly collapsed of his own accord. Seeing as he finally was down, they were determined to enjoy kicking him.

If Dylan’s wilderness years began gradually, the end of that era can be dated practically to the day, his Lazarene return heralded by the release of ‘Time Out of Mind’, in September 1997. Long-time Dylan fans watched, with a mixture of amusement and disgust, as the mainstream media executed a shamelessly abrupt volte-face. Suddenly, Dylan wasn’t a has-been any more! In fact, the media soon found themselves going to the other extreme, fostering a culture of unquestioning Dylan worship, meaning Dylan can now put out a relatively lacklustre album, such as ‘Modern Times’, and have it hailed as a masterpiece. This in itself has now given rise to a rash of articles in which critics decry other critics’ ridiculously uncritical Dylan fervour, all the while ignoring the fact that this is simply a result of the media’s own over-compensation for all those years they spent writing Dylan off. The extent to which Dylan himself must find all this amusing, is something we can only speculate about.

Dylan’s work having taken on a new lease of life, which he sustained and even surpassed on his next album, ‘Love & Theft’, his interviews also entered a new phase, becoming expansive and contemplative. Dylan’s old humour was intact, but in a new, mellower form. He now displayed a twinkly-eyed, wise old geezer-ish charm, and if he held any grudges over the shoddy treatment he’d routinely received from the press during the previous couple of decades, well, he was too polite to let it spoil the party.

It’s a great pity – which will perhaps be corrected in future editions – that Rolling Stone’s own 2006 Dylan cover story, beautifully written by the obviously Dylan-savvy Jonathan Lethem, was just too late to make the cut for inclusion here. Lethem’s piece begins with a classic Dylan line – “I don’t really have a herd of astrologers telling me what’s going to happen. I just make one move after the other, this leads to that” – and only gets better from there. We even get the marvellously self-reflexive spectacle of Dylan musing on Martin Scorsese’s ‘No Direction Home’ documentary, and its depiction of Dylan’s 1960s:

“You know, everybody makes a big deal about the Sixties. The Sixties, it’s like the Civil War days. But, I mean, you’re talking to a person who owns the Sixties. Did I ever want to acquire the Sixties? No. But I own the Sixties – who’s going to argue with me?”

We may well speculate that articles such as the ‘Spin’ piece, or some of the many missing British interviews, have been the victims of bias: pushed out to make room for more Rolling Stone pieces. Fair enough, but then why omit the short but significant David Fricke interview from 2001, in which Dylan explains why the original take of ‘Mississippi’ was held back from ‘Time Out Of Mind’:

Asked why he recut “Mississippi” for Love and Theft and produced the album himself, Dylan replies, “If you had heard the original recording, you’d see in a second. The song was pretty much laid out intact melodically, lyrically and structurally, but Lanois didn’t see it. Thought it was pedestrian. Took it down the Afro-polyrhythm route – multirhythm drumming, that sort of thing. Polyrhythm has its place, but it doesn’t work for knifelike lyrics trying to convey majesty and heroism.

“Maybe we had worked too hard on other things, I can’t remember,” Dylan continues, “but Lanois can get passionate about what he feels to be true. He’s not above smashing guitars. I never cared about that unless it was one of mine. Things got contentious once in the parking lot. He tried to convince me that the song had to be ‘sexy, sexy and more sexy.’ I know about sexy, too.”

To mark the release of his 2001 album, ‘Love & Theft’ – which included a re-recorded version of ‘Mississippi’ – Dylan gave an utterly compelling, often hilarious press conference in Rome, probably his most enjoyable and illuminating post-millennial press encounter, inexplicably missing from Rolling Stone’s collection. One particularly piquant moment comes when neither Dylan nor the assembled journalists are able to fill in the blank in the following Dylan lyric:

“Inside the museums, [ ? ] goes up on trial”

Dylan refuses to accept one journalist’s insistent claim that the missing word is ‘history’, but is also unable to supply a correction. After a five minute break, during which both parties have been able to discover that the correct lyric was, in fact, “Inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial”, the journalist involved asks, “Isn’t it the same thing?” Dylan replies, “Similar. Similar.”

You could argue that space cannot be found for everything. But then again, there are a number of eyebrow-raising inclusions here. Two interviews by Karen Hughes is two too many; the best you could say about these is that one of them is very brief. Robert Hilburn, of the LA Times, is reliably uninspired, and it’s a shame that the book ends with one of his pieces, complete with risible section headings such as ‘His Constant Changes’ and ‘Exploring His Themes’, and in which Hilburn rehashes all the most well-worn nuggets of ancient Dylan history: is there a Dylan fan alive who needs to hear, ever again, the tale of Dylan’s pilgrimage to Woody Guthrie’s sickbed?

What’s worse is that Dylan is evidently quite comfortable with Hilburn, and would give some interesting answers, if only Hilburn would ask for them. Given the chance to discuss, in detail, that wild and woolly late-period Dylan classic, ‘Highlands’, and having suggested to Dylan that “there are a dozen lines in that song alone that it’d be interesting to have you talk about”, Hilburn alights on the one single line in the song, on the album – hell, maybe even in all of Dylan – that’s least in need of explanation, elucidation, elaboration or discussion of any kind:

“…how about the one with Neil Young? ‘I’m listening to Neil Young / I gotta turn up the sound / Someone’s always yelling, / Turn it down.’ Is that a tip of the hat or…?”

Some of the best moments here come when genuinely engaged interviewers get Dylan talking about a subject he actually feels like discussing, such as songwriting. One piece which certainly can lay uncontroversial claim to being ‘essential’, is Paul Zollo’s long, detailed Dylan interview, for ‘Song Talk’ magazine in 1991:

ST: Would it be okay with you if I mentioned some lines from your songs out of context to see what response you might have to them?

Dylan: Sure. You can name anything you want to name, man.

ST: “I stand here looking at your yellow railroad/in the ruins of your balcony… [from ‘Absolutely Sweet Marie’].”

Dylan: Okay. That’s an old song. No, let’s say not even old. How old? Too old. It’s matured well. It’s like wine. Now, you know, look, that’s as complete as you can be. Every single letter in that line. It’s all true. On a literal and on an escapist level.

ST: And is it truth that adds so much resonance to it?

Dylan: Oh yeah, exactly. See, you can pull it apart and it’s like, “Yellow railroad?” Well, yeah. Yeah, yeah. All of it.

ST: “I was lying down in the reeds without any oxygen/I saw you in the wilderness among the men/I saw you drift into infinity and come back again…” [from "True Love Tends To Forget"].

Dylan: Those are probably lyrics left over from my songwriting days with Jacques Levy. To me, that’s what they sound like. Getting back to the yellow railroad, that could be from looking some place. Being a performer you travel the world. You’re not just looking off the same window everyday. You’re not just walking down the same old street. So you must make yourself observe whatever. But most of the time it hits you. You don’t have to observe. It hits you. Like “yellow railroad” could have been a blinding day when the sun was bright on a railroad someplace and it stayed on my mind. These aren’t contrived images. These are images which are just in there and have got to come out. You know, if it’s in there it’s got to come out.

Notice the way Dylan goes back to fill in more detail about the yellow railroad. Who could ever have expected Dylan to talk so openly, so straightforwardly, and about such specific details? By engaging Dylan on a subject he is genuinely passionate about, and which won’t open him up to any potential labelling or categorization, Zollo elicits one of the frankest, most revealing discussions of song-writing Dylan has ever granted.

Conversely, by repeatedly hammering away at a subject Dylan most definitely does not want to be open or honest about, Kurt Loder gets a classic Dylan interview of quite a different kind, for Rolling Stone in 1984. The world was still reeling from the shock announcement that Bob Dylan had undergone a conversion to Born-again Christianity – an event which, in the eyes of many Dylan fans, still lacks a serious rival for ‘most embarrassing occurrence in the history of the known universe’ – and Dylan was in full Fire & Brimstone mode:

KL: Do you still hope for peace?

BD: There is not going to be any peace.

KL: You don’t think it’s worth working for?

BD: No, it’s just gonna be a false peace. You can reload your rifle, and that moment you’re reloading it, that’s peace. It may last for a few years.

Cheery stuff. As he’s wont to do when badgered about his political views, Dylan refuses to even admit that he has any. When the admirably tenacious Loder tries to pin Dylan down on the assumed metaphorical subject of ‘Neighborhood Bully’ – a strong candidate for the coveted position of ‘Dylan song most Dylan fans love to hate’ – Dylan refuses to admit that the song is in any way political, “because if it were, it would fall into a certain political party. If you’re talking about it as an Israeli political song – even if it is an Israeli political song – in Israel alone, there’s maybe twenty political parties. I don’t know where that would fall, which party.”

“Definition Destroys”, Dylan once announced. And one tactic he has refined to perfection over the years is pretending to be unable to define, within context, the meaning of everyday words. Like a threatened squid puffing out a defensive cloud of ink, when pestered with attempted discussion of uncomfortable subjects, Dylan retreats into a dense fog of semantics. Here he is, telling Christopher Sykes that there’s nothing ‘political’ about ‘Masters of War’:

“I don’t know if even ‘Masters of War’ is a political song. Politics of what? If there is such a thing as politics, what is it politics of? Is it spiritual politics? Automotive politics? Governmental politics? What kind of politics? Where does this word come from, politics? Is this a Greek word or what? What does it actually mean? Everybody uses it all the time. I don’t know what the fuck it means.”

The other ‘P’ word that sets Dylan’s evasiveness gland pumping is, of course, ‘poet’. Like the Bible which he has so frequently mined for phantasmagoric imagery, Dylan’s combined historical body of published conversation can almost always be relied upon to provide a conflicting statement for any given interview quotation. And probably no subject makes this clearer than the age-old question of whether Dylan is, or considers himself, a poet. His interviews are riddled with contradictory claims about the meaning of the word ‘poetry’, and whether or not it applies to what he does. Robert Shelton reports Dylan claiming to be a poet ‘first and foremost’, and also denying any connection with the concept of ‘poet’. Asked by Nora Ephron if he considers himself primarily a poet, Dylan replies, “No… That word doesn’t mean any more than the word ‘house’”. In Zollo’s Song Talk interview, Dylan lapses into a long reverie on the meaning of ‘poet’, mainly focusing on what a poet isn’t: “Poets don’t drive cars. Poets don’t go to the supermarket. Poets don’t empty the garbage. Poets aren’t on the PTA…” And when he starts in on what poets do do, it’s still in fairly negative terms:

Dylan: The world don’t need any more poems, it’s got Shakespeare. There’s enough of everything. You name it, there’s enough of it. There was too much of it with electricity, maybe, some people said that. Some people said the light bulb was going too far. Poets live on the land. They behave in a gentlemanly way. And live by their own gentlemanly code. And die broke. Or drown in lakes. Poets usually have very unhappy endings. Look at Keats’s life. Look at Jim Morrison, if you want to call him a poet. Look at him. Although, you know, some people say that he really is in the Andes.

Zollo: Do you think so?

Dylan: Well, it never crossed my mind to think one way or another about it, but you do hear that talk. Piggyback in the Andes. Riding a donkey.

Go to Part Three: I Don’t Do Interviews >>

<< Back to Part One: Who is Mr Jones?

Do we really need another Beatles book? There must be, what, hundreds of them by now, right? Actually, the tally isn’t that vague, because last year, what the world was waiting for was finally published: a book about Beatles books. The elaborately named W. Fraser Sandercombe’s indispensible compendium, ‘Beatle Books: From Genesis to Revolution’, lists over 1,400 books about the Beatles; and of course, that total is now out of date.

Do we really need another Beatles book? There must be, what, hundreds of them by now, right? Actually, the tally isn’t that vague, because last year, what the world was waiting for was finally published: a book about Beatles books. The elaborately named W. Fraser Sandercombe’s indispensible compendium, ‘Beatle Books: From Genesis to Revolution’, lists over 1,400 books about the Beatles; and of course, that total is now out of date.