Oomska talks to: Peter Doggett

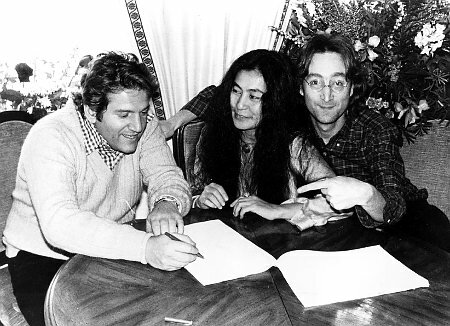

Peter Doggett’s latest book is ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’, which is out in paperback now:

Interviewed by John Carvill

I’d like to start by getting your thoughts on the current status of ‘The Beatles’, how the brand (and the cultural phenomenon) fits into our current surface-fixated celebrity culture. I suppose the ‘nodal point’ would be: what was your take on Paul McCartney’s appearance on ‘X Factor’? To be reductive, I (and, doubtless, millions of Beatles fans) would ask: why the hell did he do it?

I think there are two more questions in what you’re asking: isn’t he too famous for X Factor, and doesn’t he demean himself by appearing on it? And I can only answer by saying that (a) Paul McCartney is a populist and not an elitist; and (b) he has a different idea of his celebrity than we do.

Well, not so much “isn’t he too famous for X Factor” as “isn’t he too authentic for X Factor”, or “isn’t he (or oughtn’t he be) above that sort of thing?”

You’re bringing aesthetic judgements into a question of demographics.

Maybe. But, in a sense it was the collision of the aesthetic and the demographic that gave rise to popular culture in the first place; sadly, a similar combination – of aesthetic and societal degeneration – is now destroying that culture. Not only that, but there comes a point where actions of a merely aesthetic nature cross over into the realm of crimes against culture. Yes, McCartney is (and always was) a populist. But surely there are limits, even for him?

Do you really think that X Factor is any more crass than some of the TV shows that the Beatles appeared on in 1963? Or than ‘The Mike Yarwood Show’, where I seem to remember him plugging ‘Mull Of Kintyre’ in 1977? At the risk of sounding like Billy Joel, it’s all popular entertainment to him.

Oh definitely, it’s much more crass. And the culture it feeds (on) is correspondingly more crass. Instead of ‘Terry meets Julie’ we now have ‘Katie & Peter’. What’s most striking about ‘X Factor’ is that they have succeeded in selling ‘the process’ as their product: their audience may not be very refined, but they do register the theatricality of it all; rather than downplay this side of it, the genius of Cowell et al has been to emphasise it and make the inauthenticity of the process a – or maybe the – selling point.

Which makes me wonder: will there be any nostalgia for this inauthenticity? Our need for nostalgia, whether real or fantasised (as in, “wow, the 60s must have been amazing”), is both psychological and cultural, emotional and aesthetic. It depends on the past delivering something that we are not now, whether that is (what we assume to be) artistic worth, or the amusement of kitsch. I’ve found it interesting as I’ve grown older, watching the way in which different decades are remembered. There’s a kind of cultural grief attached to the myth of the 1960s, a sense of ‘lost time’ that affects those who lived through them and those who only wish they had done. But with the cultural revisionism of TV clip shows etc., the 70s and 80s have been reduced to celebrations of kitsch, in which the more inauthentic the original experience was, the more it is celebrated today (the glitter-ball view of the 70s, for instance, whereas my memory of that decade is altogether more grim).

If we’re laughing at today’s culture as it unfolds, however, what will be left for us, and future generations, to remember? And that ties up with what we’ve said elsewhere about the Top 100 attitude to culture: if clip shows are all we have to celebrate in tomorrow’s clip shows; and likewise throwaway cover versions from ‘X Factor’ of songs that are already hackneyed through familiarity; what’s left to remember?

Yes, that’s an excellent point. What will the kids of today have to feel nostalgic about? Certainly nostalgia would be a subject McCartney should understand. In terms of McCartney having a different perspective on his celebrity, how, do you think, does that perspective differ from the public’s view of him? I suppose I would suggest that, from ‘our’ perspective, we would argue that (a) his legacy is too valuable to sully with such antics, and (b) he doesn’t need to keep ‘topping up’ his fame. He’ll be famous for as long as the concept of ‘fame’ endures.

I think that achieving fame is a matter of ambition; preserving it, especially as long as McCartney has, is not just about talent, it’s about a deep-seated inner need that it would require a psychotherapist to uncover. I’m not (quite) saying that fame is a state of madness; but then again, look at what happens to people who are famous, and more importantly at our reaction to people who are famous. I’ve interviewed hundreds of ‘famous’ people over the past 30 years, and no matter how blasé I try to be, I always have an awareness that the other person is Someone while I’m only me. There are layers and layers of need to be uncovered in that relationship between star and audience.

Exactly. And the complexity of those layers is one of the more fascinating aspects. We know we don’t fully ‘understand’ all those layers, or how they interrelate, but our very awareness of that unknowability is partly what makes the whole thing so compelling. However, remove the ‘star’ from the equation and there is no relationship between star and audience – you’re just left with an audience, looking at themselves. Once the wee man has come out from behind his curtain, there’s no use pretending he’s still hidden from sight.

So the audience, looking at itself on Big Brother, makes itself the star, if only for a few days. (Long enough to sell an issue of Heat magazine, anyway.) I’m fascinated by the self-examination of the rock community in the early 70s, as they gradually became aware of this conundrum – Ziggy Stardust, Ray Davies’ Starmaker play, Joni Mitchell’s “star-making machinery”, etc.

So, in McCartney’s case, I think it is very difficult for us to imagine what it must be like to be that famous – and to KNOW that you’re that famous – for so long. It must create needs and insecurities that have to be piled on top of the common human ones that we all share.

I once set myself the challenge (in print) of trying to work out what Cliff Richard’s success, and entire career, meant. Here’s a man who has influenced nobody, changed nothing, invented nothing, and yet enjoyed remarkable popularity for more than 50 years. My feeling was that for his public, Cliff represents celebrity as a safety net – just as the longevity of the Queen makes even a non-royalist like myself feel that all is normal in the world, regardless of what is happening elsewhere. So Cliff equals solidity, safety, unchallenging entertainment and all sorts of other concepts that are anathema to rock fans, with their fantasy of music as a challenge to the status quo. (The band Status Quo are the rock equivalent of Cliff, ironically.)

Yet there’s something else about Cliff Richard that has enabled him to survive when all others around him have faded away – and that’s his insatiable desire for recognition and success. When I interviewed him many years ago, he knew the chart positions of all his releases all over the world, and it mattered desperately to him that (as he told me) he had the top-selling video release that year in New Zealand. On some sub-conscious level, he still believes in the old pop dictum that you’re only as big as your last single, and more than any other artist in British pop, he wants to be No. 1 – next Christmas, and every Christmas till eternity.

Paul McCartney isn’t Cliff Richard, but he’s only two years younger than him, and he was brought up in the same show-business era. It’s my belief that, like Cliff, Paul needs success and acclaim – constantly – to feel valid as a human being. It’s belief systems of this kind that get us all out of bed in the morning; maybe we think we’re only worthy if we can pull sexual partners, or make money, or score goals on Sunday morning, or whatever. For Cliff and Paul, that need has translated into a drive that has brought them phenomenal fame and wealth, and which also leaves them permanently unsatisfied: no success is ever enough.

Plus Paul McCartney and Cliff Richard share something else: a belief that mass entertainment is nothing to be ashamed of (“silly love songs”, for example). X Factor is phenomenally popular; it allows him to reach the masses; it keeps his fame alive; it boosts his ego (and we all need that, on a daily basis); and he might even have enjoyed it, and felt he was giving something back. But it won’t guarantee him a hit single next time around: those days have passed, though Paul doesn’t want to believe it.

I wonder, does McCartney sometimes succeed in convincing himself that he might have a chance at writing a hit single again?

Hit single? I’m sure he does.

Which leads me to my next question. I recall your saying that you loved ‘Chaos and Creation in the Backyard’. With all the Beatles and McCartney albums to choose from, why that one?

Why Chaos and Creation (which I called Chaos and Confusion in the book, by mistake)? Because it does everything I could wish McCartney albums to do: it’s very tuneful, it’s not self-indulgent, it’s very emotional, it’s very personal, and it sounds like the work of a man who is entirely focused on who he is and what he does best. Plus, in the shape of ‘Riding to Vanity Fair’, it includes a song that provides a lifetime’s worth of questions along the lines of: was he writing about John? George? Heather? Ringo? Himself? Or someone we’ve never heard of?

I’m amused and intrigued by your Cliff Richard comparison. But while it’s doubtless true that McCartney sees nothing wrong with “mass entertainment”, he must surely see that what constitutes “mass entertainment” today has dramatically declined since he first formed such a view. Many people take the view that the X Factor, as a cultural phenomenon as well as a TV show, is actively engaged in destroying the entire artform of popular music, which McCartney was so instrumental in creating.

And many people in the 60s took the view that the Beatles were actively engaged in destroying the lovable entertainment industry that helped them to stardom. Anyway, I’m dubious these days about any reference to popular music as an “artform”; it’s a strand of the entertainment industry. If it ever was or is an artform, that’s almost accidental, and has as much to do with what its audience requires as what its artists are doing.

To explain that further: like you, I suspect, I would stand up for the best rock and pop music as art. But I don’t think that its artistry is necessarily a facet of its existence as pop. I think that when the two collide, it’s serendipity or coincidence; and also that it’s much more difficult today, in the context of a global industry, for thoughts of art and popularity to coincide. I’m rambling a little, but there’s another long debate to be had around this subject!

We can only speculate as to what Lennon would have made of all this. Ironically, Sean Lennon defended the recent decision to license a Lennon song to Volkswagen, on the grounds that it was necessary to keep Lennon’s profile from sinking so low that he is forgotten. Can he be serious?

I laughed and groaned when I read that statement – is there nothing that these people won’t do to justify making money? But reading it again now, I’m starting to think – maybe he has a point. Reissuing Lennon’s albums won’t keep his songs alive, because nobody under 25 is buying CDs anymore; maybe selling his songs to corporations is the only way of telling people, ‘Hey, my dad was cool, and here’s the evidence’. It’s the Lennon family’s equivalent of the X Factor, if you like.

I noticed that, having performed on X Factor, McCartney tried to equivocate a bit about the show. When asked for his views on the two finalists he said something like, “I think they’re both good, and one of them is going to win.” Was that a clever piece of fence sitting? Damning with faint praise, and saying something so noncommittal that it can easily be read as signalling his disdain for the whole thing?

I didn’t see that part of the show, but from your description I wonder whether you’re reading too much into it. Ironically, for a populist, Paul McCartney is always slightly awkward in front of an audience, and he must have been aware that he was facing a very large audience at that moment, who would jump on him if they felt he was being unfair for a moment. So I think he was indeed fence-sitting, being careful not to end up on the front of tomorrow’s Sun beneath a headline like: “Macca Slags X Star”.

He did something not dissimilar on Letterman: when David Letterman asked him why this was his first appearance on his show, why he’d never been on during all the years of Letterman’s phenomenally successful show, McCartney replied, with a shrug, “Because I don’t like the show.” There was a pause while Letterman (and his audience) waited for a “no, seriously…” which never came. Again, it seemed to me like McCartney trying to have it both ways: eschewing the empty celebrity of such TV shows whilst simultaneously appearing on them.

You’re probably right. It made me laugh, though.

Going back to the all-important question of ego: there was quite a furore over McCartney wanting to alter the songwriting credits to read ‘McCartney/Lennon’ rather than ‘Lennon/McCartney’. You point out in your book that this would not be entirely unfair, since some early credits did indeed read ‘McCartney/Lennon’. But can McCartney’s ego be so desperately in need of assuaging that he would even *want* such a reversal, at this late stage, and with Lennon dead?

I don’t think fame assuages anyone’s ego. I’m not famous, but I gain ego gratification when one of my books gets a good review. I’m entirely aware, though, that the positive effects of that good review can be completely undone by a negative remark in someone’s blog or in an Amazon comment. Rationally, I know that (to quote a recent example) a glowing write-up in the Washington Post outweighs a one-star review on Amazon.com by 1,000-1 in terms of importance. But I can remember the Amazon comment almost word for word, while I’ve completely forgotten what it said in the Washington Post. So, going back to McCartney, I don’t think ‘ego’ and ‘logic’ connect very easily, for him or any of us.

Whatever the logic or fairness of making the switch, isn’t the songwriting partnership that the world so admires unalterably known as ‘Lennon & McCartney’? McCartney always came across as shrewd. Lennon once referred to him as one of the best PR men in the world. Yet over the years he has not always seemed to live up to this reputation as a master of spin, and this seems a prime example: rather than gaining from any arrangement in which his name comes before Lennon’s in the credits, he is only going to make himself look bad.

I completely understand why he gets upset about the songwriting issue; and I also know that it makes him look bad. He’s very proud to be half of ‘Lennon & McCartney’; in world-history terms, it’s going to be his eternal claim to fame. But in personal terms, he wants people to know that HE wrote ‘Yesterday’, not John. WE know that, but people in 100 years won’t, necessarily. Having done what he’s done, and knowing what he’s achieved, ought to be enough; but Paul’s merely a sensitive human, like the rest of us.

Perhaps it all goes back to your point about differing perspectives. Maybe McCartney needs better advisors, or advisors who are more willing to give him unwelcome advice?

Paul is not famous for seeking “unwelcome advice” – except in the early 80s, when he asked George Martin to produce him for a couple of albums, with decidedly mixed results. As the most successful musician in history, he is clearly entitled to believe that he knows best. But few observers would disagree that his finest work – or at least his most consistently fine work – arose from the period when he was collaborating with John Lennon, who was never slow to voice an unwelcome opinion.

Well, he might be wishing, in retrospect, that he’d listened to those who warned him about Heather Mills. What are your thoughts on the effect the collapse of his marriage to Mills may have had on his ego and his art? Maybe the darker sides of that whole affair – and the frictions the marriage caused between him and his family, Stella in particular – could rekindle his creativity?

In terms of what effect his relationship with Heather Mills had on his art (his ego was clearly damaged, as anyone’s would have been), I’d love to know more about the writing process for the Chaos album, which was apparently composed when their relationship was still strong. (It’s worth noting that on the disastrous Driving Rain album, ‘Heather’ was arguably the most ambitious and successful track.) In any case, I’m not sure that McCartney’s creativity functions best under stress; I think he’s generally at his most creative when (as during the period of Revolver and Sgt. Pepper, for example) he’s feeling self-confident. As a comparison, note how Lennon’s creativity dissipated when his self-confidence was drained, during the period between summer 72 and summer 74, and again in the late 70s.

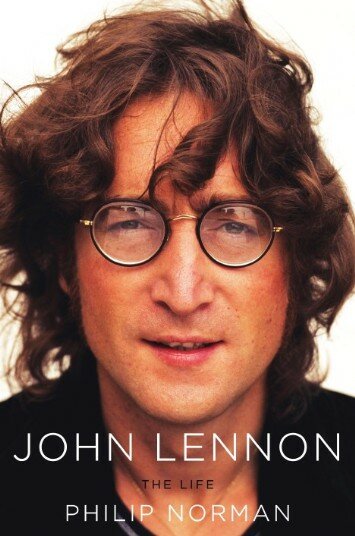

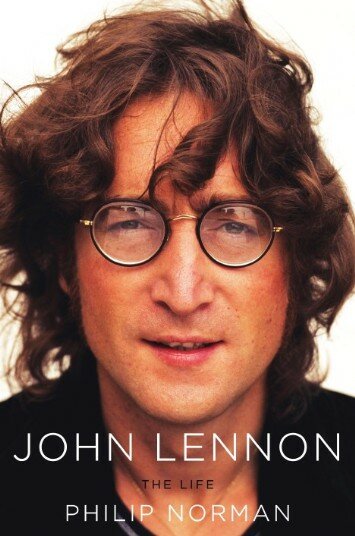

No doubt you’ve read Philip Norman’s recent Lennon biography. What did you make of that?

What a strange book Lennon was.

Bizarre, wasn’t it? Well, Norman is quite an intriguing phenomenon in his own right.He doesn’t really seem to cherish the Beatles very much, as anything more than an interesting journalistic subject.

Norman did a superb job of evoking Lennon’s childhood, and then seemed to become increasingly less interested in the story as each year passed. By the time he’d reached the 70s, he had nothing worthwhile to say.

The best part of his previous Beatles biography, ‘Shout!’, was the section focusing on the Beatles’ early years – childhood, the Cavern, Hamburg, etc. And the ‘Lennon’ book just repeated that format, filling in more detail where there was already plenty, while leaving darker corners of the story no better illuminated.

He skated over Lennon’s political involvement as though it had been the idle folly of a single weekend, rather than a crusade lasting nearly two years.

I suspect that the left-leaning nature of Lennon’s political dimension is what bothers Norman.

He added nothing to our knowledge or understanding of the relationship between Lennon and Allen Klein. And worst of all, he completely ignored all the reports about Lennon’s unhappiness during the house-husband years.

It was almost as if his chronicle of 1975 to 1980 was written to make Yoko Ono happy – the irony being that apparently she still didn’t like the book.

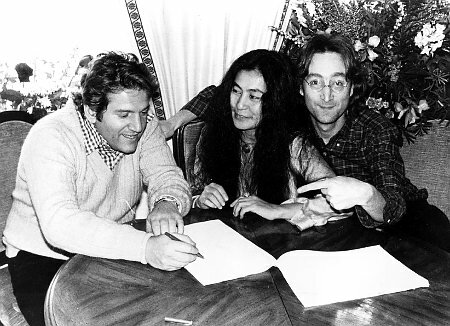

She’s hard to please! I was fascinated by your speculation about how McCartney may view the “seemingly indestructible” Ono, and the fact that she may outlive him and therefore be in a position to crucially influence his, as well as just John Lennon’s, legacy. I have to ask, have you met Yoko Ono, or communicated with her?

I’ve met and interviewed Ono twice, but not since the early 1990s. I did request an interview for There’s A Riot Going On, but didn’t get a response. For the Beatles book, I decided that – as with McCartney – she had been so widely quoted down the years that her changing views were the story, and of much more value to me and the reader than whatever this week’s party line might be. The book is really the story of the ‘process’ of being the Beatles, so today’s recollections would be less valuable than those from earlier years. (I’m not one of those writers who thinks that getting first-hand testimony about the distant past is necessarily a valuable thing. I usually trust contemporary interviews – once you’ve allowed for the mediation of the interviewer – more than modern revisions of the past, though the revisions can be fascinating in themselves, of course.

I thought that for this section of the book, Norman threw off any pretensions to being a biographer, and seemed to function merely as a PR agent. He can still write a delicious sentence, mind you.

It’s one of the reasons why your book needed to be written: Beatles books tend to fizzle out. There’s never been any halfway satisfactory attempt at documenting the breakup, and its aftermath. Rather than ‘oh do we really need another Beatles book?’, the question yours raises is ‘why haven’t there been more books like this?’

Are you looking forward to Mark Lewisohn’s forthcoming epic Beatles biography? Will that be the ‘definitive’ one?

I sincerely hope that Mark Lewisohn’s book will be The One: it should be, given the time and money he’s been able to devote to it (he said jealously). The first volume has the potential to be the most valuable, by far, if he can channel his research into Liverpool, and the England of the 1940s and 1950s, into a merging of biography and social history that brings both the Beatles and the era alive. It’s a stiff task, but I think and hope he can pull it off. My main worry for him is that, by the time the three volumes are published, there won’t be anything like the mass audience that the publishers are expecting for an epic Beatles biography of that length. So I hope he got paid upfront!

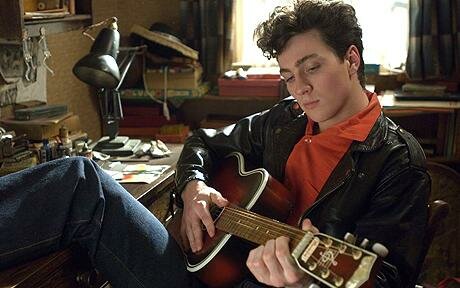

What did you think of Sam Taylor-Wood’s film, ‘Nowhere Boy’? Could you speculate on what McCartney may have made of the contrast between the actors chosen to play Lennon and himself? Presumably he will not have been happy that he was portrayed as a squeaky-voiced little imp while the Lennon role went to a handsome, muscular, cool-looking actor who seemed far older than the teenage Lennon he was meant to be channelling?

I haven’t seen the film, so it wouldn’t be fair for me to comment.

I recommend it. They managed to make a genuinely good film out of a difficult and overworked subject. It’s beautifully filmed, the acting is wonderful, and the writing is very sharp.

I’d like to get your thoughts on today’s music writing. You’ve had a long and illustrious career. How different would it be now for someone such as yourself, starting out as a writer? To what extent has the relationship between the music writer and the music business changed? What’s your view on the impact of web publishing on traditional print media?

It’s tempting to take the Private Fraser line here (from Dad’s Army), and say, “We’re doomed, doomed”. Everything has changed; nothing works the way it used to. As recently as three years ago, I could make a perfectly respectable living out of the music business – writing articles for magazines such as Mojo, compiling reissues for the major labels, writing lengthy reappraisals of artists such as the Kinks for lavish box sets. Now my income from those sources has effectively evaporated, and I’m definitely not the only one. Record companies aren’t reissuing albums and box sets the way that they were, because people don’t buy them, and anyway there are hardly any record shops left. Advertising revenue has fallen steeply, so magazines are closing, or cutting pages and staff, or altering the relationship between journalists and publishers in such a way that it is only possible to write for them by sacrificing your principles. (For more information, try putting a combination of ‘Bauer’, ‘Mojo’, ‘freelance’ and ‘copyright’ into Google.)

So for the last two years I’ve been living off books, which is a very precarious way of making a living – and would, in any case, be virtually impossible for a young music writer. Publishing is undergoing the same cutbacks as every other area of the ‘entertainment industry’.

The internet obviously has a huge amount to do with all of this. I don’t buy anything like as many albums as I used to, because I subscribe to Spotify instead. I still make the effort to buy stuff I really like, but all those casual purchases I would have made in Tower or Virgin have gone, because I live out in the sticks and there is nowhere to buy CDs.

There’s something else that isn’t often mentioned in these discussions. It’s a wild generalisation, but ‘young people’ (I suppose I’m thinking of those under 30 at the moment) don’t have the same relationship between music and print media (books or magazines) that we older people did. As an example: my younger daughter is 20, and obsessed with music, but she finds out everything she needs to know online, and she would never think about buying a music magazine (she gave up her NME subscription years ago), let alone a book about music. She reads a lot, but why would she want to read about something she can listen to?

For me, as a teenager in the 70s, reading was my only way of stepping into the magical world of rock/pop/whatever the hell it is. So it still comes naturally to me. But even I find it hard to slog through music magazines these days, as it all seems second-hand. You already know everything they’re going to tell you, either because they’re rehashing the past again, or because you’ve already seen it on a website. (Let’s skip over the appalling decay of rock criticism into ‘100 Greatest Albums of All Time’ list-features.) For the most part, the only music books that sell these days are ‘my-coke-groupie-hell’ memoirs and biogs.

Blogs, web magazines and web forums are the last bastion of the old ethos of rock journalism & criticism. I’ve been blogging myself in recent months about the Beatles, when I can find the time, not because I think it’s going to sell any copies of my book but because I enjoy it, and it offers a home for random thoughts that don’t belong in a book. But I don’t see a way of making any reasonable money out of it. If you do, please let me know.

I plan to keep writing until I drop, and if I can continue to get books published, then that’s what I’ll do. But I don’t believe in my heart that there’s a financial future in it, so at the age of 53, I’m looking for other things to do with my working life, on the assumption that being an author soon won’t count as a career anymore. It’s not the way I’d like things to be, but I have to be realistic.

Many writers and critics say the same thing: the potential income to be derived from music writing has dramatically declined. And there seems no prospect of a reversal of this trend. The online world has brought many benefits, but does it risk destroying the print media? Do we risk this being a one-way process: there may come a point when people realise that they miss the traditional media, but once, say, a national newspaper is gone, it’s gone.

Quite. The internet is a remarkable thing, but when it was invented/developed, nobody realised quite what the ramifications would be for every area of our lives. Without writing 10,000 words on this subject, I can only express it in personal terms. I used to make a perfectly adequate living out of writing rock journalism, and working with record companies on reissue projects. Now my income from those two sources has been reduced to virtually zero – and I’m in the very fortunate position of having years of experience and a degree of reputation under my belt. So I feel for anyone attempting to start out now on the same road.

And I fear for my daily newspaper. I could read The Guardian online for free, but it doesn’t suit the rhythm of my life, and I’d much rather pay for the ‘real thing’. In a decade’s time, though, I may not have the choice: all our mainstream news may come filtered through Rupert Murdoch and his spawn. You don’t need to impose a political dictatorship if you control the mass media. It could all be bread, circuses, and blatant corruption behind our backs. Interesting times . . .

One of the great debating points associated with the whole ‘new media’ phenomenon, is whether the ‘democratic’ nature of the Internet is to be celebrated or feared. Up until, what, around a decade ago, the sort of amateur critics who now write for or run websites, would have had no reasonable expectation of seeing their work published. What’s interesting is the extent to which newspapers are now beginning to implant online media publications within their pages. This often takes the form of quaint little columns of the ‘Online Rumblings’ variety; a much more potent indicator of what’s to come is that many print reviews now contain – indeed, often commence with – an overview of what’s being said online.

I think this last phenomenon, which is inescapable (“but don’t forget to text us and let us know what YOU think”), reflects not only a demolishing of the old barriers, but also a panic-stricken response to the existence of the internet. The modern audience is a lot more vocal and visible than in the days when 10 minutes of BBC-TV’s Points Of View every week felt like a privilege and a novelty. But at what point does the concentration on the opinions of the public at large destroy the justification for having ‘expert’ opinions at all? I might watch (as an example) Nick Robinson on the BBC news because I value his judgement about politics. At what point does Nick Robinson vanish, so that everyone else can have their say?

The same sorts of questions are continually asked about the effect of illegal downloading on CD sales. But the music industry has a lot to answer for, not least in making CDs the dominant media in the first place. Nobody can download a vinyl LP, but if a digital download can give you the same quality, why buy a disc? If a legal download offers no advantage over an illegal one, you can see why many people are tempted to take that route, particularly if they’ve already bought a given album in one or more older formats. Factor in the way in which we’ve all been sold reissues, remasters, box sets, alternate takes, etc., and you can also see why many people don’t regard illegal downloading as ‘stealing’.

Exactly. Those of us who are hard-wired to buy music legitimately are feeling short-changed by the way the industry has exploited us down the years; and those under 25 no longer associate the music they love with the formats that the industry wants them to buy. We could discuss this all day, but here are a few quick thoughts. We lived through years when the music industry tried to tell us that CDs needed to cost £15 or more because they were worth that much money. Then they started licensing their music to national newspapers to give away, effectively for free, while allowing chain stores (HMV and the like) to sell albums like the Who’s greatest hits – which, rationally, ought to have been a valuable asset for decades to come – for a fiver. The message was, increasingly, that music isn’t worth anything. And then they wonder why people no longer want to pay for it. Even I rarely buy CDs anymore, though I do pay a subscription every month to Spotify, because I can’t stand the adverts. I end up sampling a lot of music that I might once have bought so I could hear it; now, once I’ve heard it, I don’t need to own it. It’s a massive shift in my attitude to music. If the former editor of Record Collector no longer feels the need to own music formats, then the industry is (impolitely) fucked.

There’s also a line of thinking that says popular music, as we have known it, has pretty much run its course. This is not so much a reflection on the limitations of the art form itself; instead, it’s the result of a number of technological and sociological changes which have, ironically, been sped along by the influence of pop music itself. The kind of world which produced The Beatles, or even, say, Punk, no longer exists. Any truth in that?

Obviously the world has changed; obviously the internet has increased the speed of that change. And I wouldn’t disagree with your fundamental point. Music was the secret language of youth; then the increasingly vocal language of the youth culture/counter-culture/alternative culture; and now it’s global wallpaper, inescapable and culturally empty. You can’t expect to generate the same fanatical desire and respect for something that’s everywhere as you could when even listening to rock’n’roll or pop was a ‘political’ (in the widest possible sense of the word) statement. That doesn’t make older music ‘better’ than new (though it probably makes it ‘fresher’); but older music certainly occupied a different, and more valued, space in people’s lives.

You make the point that there has been a steep decline in the quality of much music journalism, with magazines taking increasingly populist and sensationalist approaches, as well as regurgitating pointless ‘Best 50 albums which didn’t appear in last month’s list’ lists, etc. Could it be argued that this trend dovetails, to an extent, with the winding down of popular music itself? If pop has said all (or most) or what it has to say, then isn’t it logical that the pop music press dies with it?

Yes, yes, and yes. There will always be popular music; what there may never be again is a specific CULTURE of popular music. It didn’t need to exist before rock’n’roll, and it doesn’t exist today. There are and will be stars, and people will want to know about them – enter Heat magazine and the rest, most of them online. But cultural debate of rock music will soon be confined to the universities, where it can take its place in the Cultural Studies forum alongside academic consideration of the narrative arc of Coronation Street, or the semiotics of Countdown.

Right, but that specific culture is one of the things that made pop music so enjoyable, and so important. The fact that the music came as part and parcel of a wider cultural process was part of its appeal. On the other hand, there’s no point in shiny wrappers which don’t have any sweets inside them. ‘X Factor’, which McCartney has been seen to have been endorsing, is all process, it’s all packaging and commerciality. The consumers of the end product – whether you consider ‘product’ in this context to mean either the novelty records made by briefly notorious performers, or the process by which these performers are corralled, herded, branded and sold – are getting a poor deal. But society as a whole is getting an even worse one.

I agree, of course. But the problem is that you can’t invent an equivalent to that culture of popular music; it has to emerge, out of need or desire. As I explored in , even that idealistic ‘rock culture’ was born out of, and quickly exploited by, commercialism. In a corporate global economy, where we’re dependent on corporate technology to host our ‘counter-culture’, it’s probably harder than ever before to escape culture as ‘product’.

One final point: there is still lots of great music being made today. But I don’t need it, the way that I used to. I don’t care if I hear it or not; I don’t care if I own it or not. There’s only one exception: Rufus Wainwright, who still makes me feel like a fan, rather than an observer. For what it’s worth, I feel the same way about movies – but not about books.

You’re right, there is a lot of great stuff around. But even the best of it still feels like a footnote in an appendix.

Maybe this interview should come with a free pistol, so that those of us over a certain age can retire to our drawing-rooms and do the only rational thing. Or, as my daughter would say, we should just ‘get over it’ and be thankful that we were alive when we were.

I’ll be sure to preface the article with some sort of disclaimer.

There’s a great book to be written about the nature of these changes, and where they may take us. In fact there are almost certainly a number of books already published on the subject. It’d be interesting to find out how many are written by members of the old, traditional print media, and how many by aficionados of new media publishing. Probably they’re mostly by academics.

And only read by other academics and their students, in a world that will struggle to survive the current austerity measures. Learning for the purpose of expanding the mind and imagination now seems to be totally discredited; what happens when all of the students with Media Studies degrees realise that they can’t get jobs in the media? Rhetorical question!

Could it be that new media may not take over, it could fizzle out? Look at how ‘dance music’ dominated pop music in the 1990s, but now it’s all back to groups with guitars and lyrics. Or the ‘movie brats’ of the late 60s and 1970s, the Scorseses and Coppolas, film students and media enthusiasts who ‘took over’; for a while but who eventually blew it, and control reverted to big studios etc. What’s known as ‘Independent’ film flourished again in the 1990s, with Miramax etc. but again the cycle came round. Miramax is now owned by Disney and the big studio blockbuster is more entrenched than ever.

Yes, at my most paranoid I keep waiting for a government (or a corporation, the real face of 1984) to announce that the internet will be closed down, or abolished, or controlled under strict Department of Interior Security regulations. This is going to be a particularly tough genie to squeeze back into a bottle, however.

Ok, lets get back to the Beatles! I knew there were long-festering tensions between George and Paul, but I didn’t realise the extent of them until I read your book. George was often complaining of Paul treating him like his “little brother” and it seems Paul never registered this as he actually referred to George, on the day of George’s death, as being like his “little brother”. I expect the Harrison family winced a little at that. Why do you think Paul couldn’t adjust his behaviour and attitude towards George?

I’d never made that “little brother” connection – I think that’s very interesting. I’m sure Paul didn’t mean it in a belittling way; after what happened in the wake of John Lennon’s death, he was being very careful in what he said. And heartfelt too, I’m sure.

As an observer/outsider, my take on McCartney’s relationship with Harrison was that Paul couldn’t understand what it was that kept upsetting George so much; and the more he tried to do things differently, the more George resented it. It’s very difficult in life to escape unconscious patterns of behaviour, even if you know (rationally, consciously) that they don’t work for you or those around you. I don’t think George could stop feeling hurt by Paul; I don’t think Paul could stop treating George like a junior partner. They almost needed to rethink their neural connections, which is the work of therapy or something equally profound. Saying to yourself, “I must take George more seriously” isn’t going to do it. (Which is why, as a complete distraction, the NHS concentration on CBT as a ‘cure’ for mental/psychological problems is completely inadequate, as it only scrapes the surface of the problem. But I digress!)

Underneath it all, I believe that Paul sincerely loved George; and at some level George loved Paul as well. But they had a hard time expressing it.

The recent, long-awaited Beatles ‘Remasters’, and the associated Rock Band game, got a lot of publicity. What did we learn from these regarding the relationships between Apple/EMI and Paul/Ringo/Yoko/Olivia?

Although I was very critical in You Never Give Me Your Money about most of the Beatles’ corporate activities since the Anthology, they (two Beatles, two widows, lots of lawyers) have obviously been much more restrained in their handling of the Beatles’ heritage than they could have been. The four main parties seem to have an instinctive distrust of all new ideas, and a reluctance to agree with each other too easily, which has the positive benefit of making sure that new ‘product’ only appears after lengthy debate, and the negative result of turning every Beatles project into a saga. But they have found a way of working together which has involved enormous (and admirable) sacrifice on the part of Paul McCartney, who has had to allow Yoko and Olivia to out-vote him on many ideas, even though he was a Beatle and they weren’t.

The relationship with EMI is much more uncertain. Both Apple/Beatles and EMI were obviously very anxious, as a team, to get the remastered CDs into the shops as quickly and lucratively as possible. But those two adverbs rarely go together in the Beatles’ world. There is a long history (chronicled in my book) of legal and financial disputes between the two sides which has inevitably made them both very suspicious. And the world keeps changing, throwing up new challenges that didn’t exist when contractual settlements were agreed. The most prominent problem in recent years has been the non-appearance of the Beatles’ music on iTunes. Both Apple/Beatles and EMI stand to make millions from legal digital downloads of the Beatles’ music. But both sides are so desperate not to give away percentage points of the profits to the other that they have chosen to argue, and both lose money, than reach a settlement and both get rich(er). The Beatles can afford to wait; EMI can’t, and my guess is that eventually they will have to give way, and agree to what Apple/Beatles want. But by then much of the potential market will have been lost to illegal downloads. The moral of the story: lawyers always make money.

Apparently there will now be vinyl versions of the remastered box sets. After that, what releases do we have to look forward to? The White Album demos, perhaps, or the Let It Be film?

Though the rumours were denied, I think there is definitely some truth to the suspicion that Paul and Ringo aren’t keen to see a super, deluxe edition of the Let It Be film in the shops, because it damages the Beatles’ legend (or myth, if you prefer). It was noticeable (and probably a coincidence) that when my book was published last year, documenting all the disputes in the Lennon/McCartney relationship between 1968 and 1980, Paul McCartney gave a succession of interviews in which he kept insisting that the two men were always close friends, and that they had completely repaired their relationship by the time John died. Likewise, the official Apple documentary that accompanied the Remasters last year effectively obscured the fact that the group had broken up, let alone fallen out with each other and ended up in the law courts.

So why would the Beatles want to reissue a film that, even in its sanitised state, hints at how poor inter-group relations were in 1969? And how could they add more material to a DVD release without tarnishing the all-for-one image even further? In corporate terms, it makes no sense to damage the brand like that. Personally, I’d love to see all the out-takes, no matter how grisly. But I can understand their point of view, of course I can.

The White Album demos are a different matter entirely. They would make for a fabulous album, in both historical and musical terms. But my gut feeling is that it will never happen, because the potential profits wouldn’t be big enough for the corporation (Apple/Beatles) to be bothered with. It would be a release for the fans, rather than the masses, and Apple haven’t shown much sign in recent years of thinking that the fans are any more important than the general public.

That said, EMI are about to announce reissues of much of the non-Beatles Apple catalogue, which can only be for the benefit of fans, so what do I know?!

Speaking of Lennon, I see the Lennon solo albums are being remastered again. Is this purely a financial project or will it have any worth?

It’s a financial project, clearly. The only worthwhile addition to the Lennon catalogue would be a series of extended reissues – a three-CD set of Plastic Ono Band, for example, tracing each song from original demo through out-takes to the finished master. Anything else is merely a commercial venture – especially if it turns out to be all the albums we already own, stuffed in a box with a handful of bonus tracks. People simply won’t buy that kind of product anymore.

The consensus seems to be that the Beatles remasters came off quite well. OK, there was some compression and tweaking on the stereo remasters, but the mono discs at least retained some semblance of purity. And of course, they must have pulled in quite a bit of cash for EMI. Now the world awaits the vinyl versions of the remasters. Do you have any thoughts on the digital versus vinyl debate, in terms of sound quality and listening experience?

Not really. I bought a couple of the stereo CD remasters to play in the car, and I did briefly compare them to the originals, and thought they sounded impressive. I didn’t need them, though, as I rarely play the Beatles’ records – they’re ingrained in my memory forever, and don’t need topping up. What I really wanted, as a fan, was the mono set, but not at that price. And I won’t be buying the vinyl, as I don’t really listen to vinyl anymore – because I’m usually in this room when I listen to music, and the vinyl deck is in the next room. It’s as simple and stupid as that!

Your book’s opening scenes, depicting Lennon’s murder and its immediate aftermath, are highly evocative and deeply affecting. But there is also some humour in there. We can’t help marvelling today at a world where, even in a rock star’s mansion, “the phone” is kept under the stairs, and that in fact neither George Harrison nor Paul McCartney were initially reachable by phone. The olden days, eh?

And it’s quite telling, at the same time. Harrison chose to hide the phone under the stairs to keep the outside world at bay; and McCartney likewise disconnected his every night, to preserve his family’s privacy. It’s hard to imagine either of them tweeting their every thought or action to a voracious public. Demanding that form of access to people’s lives – whether they’re friends or idols – strikes me as a kind of cannibalism.

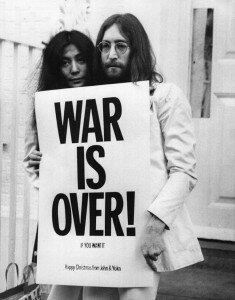

Lennon was (and still is, posthumously) often mocked for his political stances. Do you think he had a sort of bipolar relationship with his political commitment, one day passionately involved, the next day more interested in what he was having for breakfast?

Definitely not bipolar. I think he was 100% committed when he was committed: after all, few public figures have chosen to make themselves appear so vulnerable, and often ridiculous, for their chosen causes. But he was also (like most of us) self-obsessed – hence his conviction that it was a form of art to document his life between 1969 and 1972, public and private. Of all the four Beatles, he is the only one who I can imagine tweeting for peace, or revolution, or whatever.

I have a great deal of respect for Lennon’s political convictions, if not always for the methods whereby he pursued them. But he contributed to the mockery by his own subsequent disavowal of his beliefs and actions.

One of the most disturbing claims made about Lennon’s political involvements is that he supported the IRA. In your book, you say he “maintained contact” with them even after most UK radicals, who had been instinctively sympathetic to the Republican movement in general, had backed away in horror at the bombings and civilian deaths. Just how naive was Lennon on this subject? Do you think he ever donated any money to the IRA?

I think Yoko Ono is right when she says that she and Lennon never contributed money directly to the IRA. But he did definitely give money to the republican movement in Ireland, both as donations, and via his earnings from the song ‘Luck Of The Irish’, which were given to the fundraising group Noraid. Check out Noraid on Google, and you’ll see that there has been an ongoing debate since the early 1970s about the precise nature of that organisation, and what its money has been used to buy. My gut feeling is that Lennon donated out of sympathy and political outrage, and didn’t care too much about what happened next. But he was, after all, 3,000 miles removed from what was happening in Ireland, and in Britain, in 1972, so I’m sure there was a certain amount of naivety involved.

If Lennon had lived, do you think a Beatles reunion of some sort would have been inevitable? What do you think that would have been like?

“If Lennon had lived” – I remember many years ago being asked what I thought would have happened if he hadn’t been killed, and saying: “He would have died”. I wasn’t just being glib; my instinct is that he wasn’t in great physical or mental shape in 1980, and so the possibility of an accident of some sort was always just around the corner.

If, however, he had lived and prospered, and was still alive today, then I think it would indeed have been inevitable that he and McCartney, at the very least, would have agreed to perform together at Live Aid or something similar. It would have been very emotional, we’d all have had enormous lumps in our throats, but it wouldn’t have changed the world beyond that particular fundraising event. I certainly don’t think that it would have been possible for the four Beatles to work together long enough to make an album, or stage a concert tour. And although I wanted those things to happen, I’m glad in retrospect that they didn’t, because the Beatles could never have recreated the musical and social impact that they made on the 1960s.

It’s striking that there is still some doubt over the exact details of why, when, and at whose instigation the Beatles split up. At one point you suggest that McCartney may have “capsized the Beatles in a fit of pique” over a letter from Harrison and Lennon.

The split was like a divorce; and although some divorces happen because of a single incident, most of them are a slow process of decay. And that’s what happened with the Beatles. None of them set out to reach the positions they found themselves in by the end of 1970; but a long series of events, some of them incredibly trivial, contributed to that decay. Because Paul McCartney was generally the one being placed under most psychological pressure by his colleagues, he was the one whose decisions had the biggest impact on the split. But that doesn’t make him responsible: they all were.

The incident you’re referring to was interpreted by Paul as a calculated slap in the face by two of his best friends, and he reacted by sending out the press release that accompanied the McCartney album, and thereby triggering the worldwide ‘Beatles split’ stories. But at any stage one or more of the Beatles could have made a concerted effort to prevent this decay from worsening, and none of them did. Ultimately, and to varying degrees, I think they all wanted it to be over, whether they realised it consciously or not.

I was interested to read that Paul McCartney had been surreptitiously purchasing shares in Northern Songs, without Lennon’s knowledge. To what extent do you think that was a factor in the breakdown of the Lennon McCartney relationship?

In practical terms, not at all; in terms of trust, it meant a lot. It demonstrated to Lennon that McCartney was no longer effectively under his control as a member of the Beatles, and was capable of acting independently in his own selfish interests – exactly as Lennon had been doing for the previous year.

At one stage, George Harrison had an affair with Ringo’s wife Maureen, which led to the collapse of Ringo’s marriage. How do you think George and Ringo managed to maintain a relationship afterwards, and how do George’s actions fit with his spiritual lifestyle?

Both the Harrison and Starkey marriages were under impossible strain at this point, and it’s entirely likely that both men might have been straying themselves, so I think this affair merely accelerated the decline of the two relationships. I agree that it’s amazing George and Ringo remained (or became, once again) close friends; just as it’s equally amazing the Harrison/Clapton relationship survived after Pattie Boyd left one man for the other. (I don’t think Lennon and McCartney would still have been talking if Yoko Ono or Linda Eastman had had an affair with the other man!) But all three men clearly decided that male friendship, and musical bonds, were more important than jealousy, or maybe more important than their marriages at the time.

The contrary nature of George Harrison’s spirituality deserves a book that will probably never be written, because it would need his widow Olivia to spill all her marital beans – and why should she? All of his friends said how sincere he was about his spiritual beliefs; yet many of them also reported that he was bitter about the Beatles and his financial misfortunes, and there have also been plenty of stories about his personal conduct that don’t exactly scream “I’m spiritually righteous”. I guess he was only human after all.

It’s shocking to find Paul McCartney, in the midst of the Peace and Love era, leaving a note for John and Yoko saying ‘You and your Jap tart think you’re hot shit’. How did you learn about this and why do you think Paul would have behaved so terribly ?

The story comes from Paul’s girlfriend at the time, Francie Schwarz, who was (like John and Yoko) living with him at that point. She says that Paul said it was a joke; but it betrays a desperate bitterness and hurt about the transfer of Lennon’s friendship from him to Yoko. Lennon and McCartney had the kind of relationship where they could say anything to each other; I’m sure Lennon had been equally blunt and insulting to McCartney down the years. But on this occasion Paul didn’t seem to realise that there was one subject that John was not prepared to joke about: his relationship with Yoko. Before anyone asks, do I think that McCartney was a racist? No, I don’t. But, as Cynthia Lennon once told me, all four Beatles were Liverpool chauvinist pigs in the 1960s.

How do you think Paul and Yoko get along these days ? Is it a case of they are forced to deal with each other, forever tied together as the two remaining halves of the Lennon McCartney partnership, or is there any genuine affection and/or respect there?

Speaking strictly as an outsider, I reckon it’s a purely business relationship which conceals a certain amount of respect, but which doesn’t spill over into genuine friendship. Both of them have, for the most part, decided that it’s better to pay lip service to each other in John’s memory (with occasional lapses on both sides), but I can’t imagine that they would seek out each other’s company unless they had to.

You’re clearly trying for at least a partial rehabilitation of Magic Alex. You think he has been unfairly treated by the media over the years?

I do, yes, because the portrayal of him has been 100% negative, and that’s rarely a fair evaluation of anybody. I was cynical before I met him, and very wary when I did finally meet him, but I spent enough time with him to appreciate him as a rounded human being, rather than the virtual con-artist portrayed in so many books about the Beatles. And I did find his version of what happened with the recording studio at Apple very convincing.

Could it really be the case that George Martin, or Abbey Road engineers, sabotaged Alex’s studio?

I’ve never said that George Martin or any other individual ‘sabotaged’ Alex’s studio. But Alex pointed out to me that it was very much in the interest of the EMI-based staffs who were working with the Beatles in the late 60s for his prospective studio NOT to work, because it would take their prime asset away from Abbey Road. So there was no incentive for EMI personnel to make the Mardas equipment operate properly. In any case, it’s Alex’s contention that the equipment that was taken from his Apple Electronics lab and briefly installed in the basement at 3 Savile Row was never intended to be a working studio – it was merely a prototype meant to illustrate the possibilities of what could be achieved with multi-track recording.

When you interviewed Alex, did you ask him about the events which led to the Beatles falling out with the Maharishi?

I did, and he was adamant that he did not set out to turn John Lennon against the Maharishi, as most accounts claim. He said that John made up his own mind about what was going on, and that’s why he decided to leave.

You’re even quite kind to Allen Klein. Certainly he did make money for the Beatles, but they spent a lot of it getting rid of him. It’s yet another irony that Lennon’s uncompromising demand that Klein manage their affairs was a major contributing factor in splitting the group up, yet Lennon ended up falling out with Klein himself, and writing ‘Steel and Glass’ as an attack on him. What do you think the “tough little scorpion” thought of that track?

I wonder, in fact, if John ever did fall out with Klein on a personal basis. There’s no actual evidence of that. He was still hymning Klein’s praises in interviews in late summer 1972; and I’ve also seen very friendly correspondence from Lennon to Klein in the summer of 1973, at a point when the two sides were firing lawsuits at each other, and yet John is still signing his messages “love” or “lots of love”. That doesn’t suggest hatred. And don’t forget that it was Klein who told Lennon in 1975 that his Rock’n’Roll album was about to be ‘pirated’, in effect, by Morris Levy – several months after ‘Steel And Glass’ was released. Maybe Klein didn’t think that ‘Steel And Glass’ was about him; maybe, in fact, Lennon had already TOLD him that it wasn’t about him. Or maybe it was, and Klein treated it as friendly badinage, rather than vicious insult.

As with Magic Alex, I was very keen to show that there was more than one side to the accepted story. Klein clearly had his own interests at heart during his involvement with the Beatles, but so would anyone in that situation – and there were many occasions on which he put together deals that proved to be very advantageous to the Beatles, together and separately. So he was not 100% the villain he’s usually assumed to have been.

I’d heard of Mal Evans providing sound effects on Beatles records – “playing the anvil” on Maxwell’s Silver Hammer, etc. But your book contains the first mention I’ve read of claims that it was “an open secret” in Beatles circles that Evans had actually “contributed some lines to the Sgt. Pepper album”. Can this really be the case?

Mal certainly told everyone who knew him that he had offered some lyrics to a couple of songs on that record – off the top of my head, I think it was the title track and ‘Fixing A Hole’. And at the time he died, he was hoping for a financial gesture of some sort from Paul, I think, to recognise the fact, although I’m sure that he would not have received a songwriting credit. Were his contributions more significant than those that Derek Taylor made to ‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’? Perhaps not. In strict legal terms, Taylor and Evans might have had a case for claiming a small proportion of the proceeds of those songs. But Taylor, at least, realised that there was a vast difference between tossing a couple of lyrical images in Lennon’s direction, and claiming to be a songwriter.

I assume you agree with those who argue we should preserve Ringo’s house in Madryn Street, currently scheduled for demolition? What do you think the demolition of Beatles landmarks says about our country’s attitude to its own cultural heritage? Speaking of which, did you happen to see the BBC documentary about the National Trust’s restoration of John Lennon’s house?

I didn’t see the documentary, but I have visited John Lennon’s house – or Aunt Mimi’s, to be 100% accurate – and I found it a much more moving experience than I would have expected. I’m less sure about the case for preserving Ringo’s house, more than anyone else’s, because it wasn’t in itself a significant landmark in the Beatles’ story. Otherwise we’d be preserving every house where any of them had ever spent the night. I’m as nostalgic about our collective heritage as anyone, but you can’t preserve everything from the past indefinitely, or else it chokes the future.

Have you been up to Penny Lane in recent years? The ‘shelter in the middle of a roundabout’, in Smithdown Place, was some sort of cafe or bistro for many years, but that’s closed down now and the building is derelict. It seems incredible that such a landmark would be in disuse. I suppose if it were in the United States it would be a theme park by now.

This is difficult, isn’t it? My first emotional response is outrage; then I think, “Why should Liverpool have to exist as a permanent museum for the Beatles? Can’t it be allowed to grow?” I have similar feelings about the basement opposite Ealing Broadway station where the Rolling Stones played many of their earliest gigs, in what was then the Ealing Jazz Club. Part of me wants it to be a shrine – complete, I suppose, with T-shirt shop and café – and part of me thinks that it’s enough that somebody still remembers where the venue used to be.

Finally a few standard quick-fire quiz questions….

Your favourite Beatles album?

The White Album, probably, though I will always have a soft spot for the first albums I heard, which were With The Beatles and A Hard Day’s Night, both in 1970.

Favourite Beatles film?

Let It Be, with another emotional tip of the hat to A Hard Day’s Night, for setting me on the road to Beatlemania.

Best Beatles book you’ve read?

Derek Taylor’s As Time Goes By or Fifty Years Adrift.

And, of course, everyone who’s read your book will want to know what you’re working on next.

A book on David Bowie and the culture of the 1970s – in effect, the book that Ian MacDonald had been commissioned to write when he sadly took his own life, which would effectively have been the successor to Revolution In The Head. It’s for the same editor who worked with Ian, but it won’t be imitation MacDonald, as I’m sure our respective takes on Bowie would have been quite different.

It’s been great chatting with you, Peter. Many thanks for taking the time. I hope we can speak again in future, certainly I’ll be first in line for a copy of the Bowie book.

Anybody who has read all the way down here, and hasn’t yet secured themselves a copy of ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’, really ought to correct that oversight forthwith:

‘You Never Give Me Your Money’ was the first book ever reviewed here on oomska. You can read our thoughts on it here:

‘You Never Give Me Your Money: The Battle for the Soul of The Beatles’

This interview was conducted, via email, over a period of several months. As is the case with all oomska interviews, the interviewee was shown a copy of the article prior to publication.