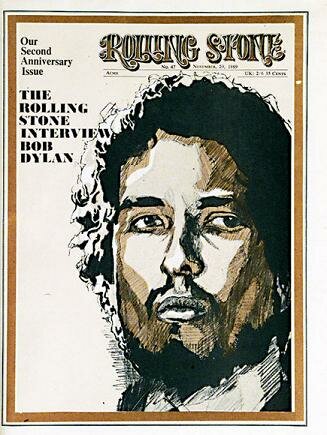

You Had To Ask Me Where It Was At: Bob Dylan & the Media

An exploration of Dylan’s media relations, as refracted through Rolling Stone’s anthology of ‘essential’ Dylan interviews and press conference transcripts.

by John Carvill

Part Three: I Don’t Do Interviews

Is Bob Dylan a poet? It depends on who’s asking, and why. There’s an interesting debate to be had, concerning whether song lyrics (Dylan’s or anyone’s) can be considered as ‘poetry’; but the people who generally focus on whether what Bob Dylan writes can be viewed as poetry are seldom approaching the question from an objective standpoint. More often, they’re working to an agenda. Dylan was so phenomenally remarkable to the media in the early days, he was so unique and so unprecedented, that they had absolutely no frame of reference in which to place him. The nearest thing they could think of to Dylan was a poet, and when they tried that on for size and found it didn’t fit, they made the further error of blaming him for it. In other words, they pinned an inadequate label on him, and then castigated him for not matching up to their reductive categorisation.

The essential point, never mentioned by the press, is that asking whether Dylan’s lyrics work as ‘poetry’, then deciding that they don’t, is based on a false premise. It’s like asking whether a gourmet meal stands up as raw meat. Although Dylan’s lyrics, removed form the musical context, still make for interesting reading and retain some of their power, the fact is they were never designed to be considered in isolation. As Dylan himself points out:

“A lot of times people will take the music out of my lyrics and just read them as lyrics. That’s not really fair because the music and the lyrics I’ve always felt are pretty closely wrapped up. You can’t separate one from the other that simply. A lot of time the meaning is more in the way a line is sung, and not just in the line.”

Which points up a serious problem with this collection. Many of these interviews are circulating in audio format, and there’s a huge qualitative difference between reading an interview and listening to a tape of it. So much of the pleasure to be derived from audio interviews lies in Dylan’s uniquely characterful enunciations, infinitely nuanced inflections, and idiosyncratic speech patterns – how he leans down on one word, or elongaaaaaaates another – so that how he is saying something becomes as, or more, important than what he’s saying, and, as with Dylan’s delivery of lyrics, there are plenty of instances where how he’s saying something is the something he’s saying.

To an extent, this is also true of Dylan’s interviewers themselves; hearing their voices ringing out across the decades gives us a sharper and more resonant sense of those times. When Studs Turkel addresses him with his full name – “How can we describe you, Bob Dylan, rumpled trousers, curly hair…” – it sounds formal and quaint; when Cynthia Gooding does the same – “Why yes. That’s just what I had in mind, Bob Dylan” – it sounds intimate and suffused with emotional warmth. Dylan’s 1962 ‘Folksingers Choice’ interview with Gooding, for WBAI Radio in New York, is well worth reading. But it needs to be heard to appreciate the obvious chemistry between the two. Gooding was a singer herself, and had first met Dylan at a party, in 1959, when he was a very young man. It’s clear that Dylan is affectionate towards her – though it doesn’t stop him from telling outrageous lies about travelling with the carnival and working on the Ferris wheel. But his fondness for the older woman is far outstripped by Gooding’s flirtatious, almost worshipful approach to him. After Dylan plays ‘Smokestack Lightening’, and asks Gooding, “You like that?”, the way she purrs, “Yeah, I sure do”, sounds positively post-coital. Even more so after he plays ‘Hard Travellin’:

CG: Nice, you started off slow but boy you ended up…

BD: Yeah, that’s a thing of mine there.

Similarly, there are plenty of laughs to be had from reading transcripts of the 2001 Rome press conference, but no written account can possibly get across the sheer delight of hearing how Dylan pronounces the word ‘lure’ in the following exchange:

Q: Do you go on the Internet?

D: I’m afraid to go on the Internet. I’m afraid some pervert is gonna lure me somewhere!

Dylan’s argumentative conversations with AJ Weberman (the original Garbologist, and self-appointed ‘Minister of Defence’ for the ‘Dylan Liberation Front’) were condensed into an article for the ‘East Village Other’ in 1971, included here. Dylan’s incredulity at Weberman’s benignly deranged fanaticism is amusing and interesting to read. But the recordings of Dylan’s telephone conversations with Weberman are the kind of thing you can hardly concentrate on listening to because you’re too busy struggling to convince yourself that they can really exist. Although the two tussle over wider issues such as politics, and Dylan’s escalating horror of Weberman’s ‘Dylanology’, it’s the little nitpicking details that are truly priceless. You really need the audio to properly enjoy Dylan insisting that Weberman remove some lines from his written account of an earlier conversation, lest they expose Dylan to Sara’s ire: “My wife will fuckin’ hit me, man!” Better yet, you can revel in the realisation that, when Dylan tells Weberman he’ll have to wait until after the weekend to bring his article round for Dylan to go over it with him, because Dylan is ‘working’ at the weekend, he doesn’t mean he’s going into a recording studio:

AW: Should I bring it round now, or…

BD: No, no, I’m tied up the weekend. How about, like, on Monday or Tuesday?

AW: Ah… see the trouble is that these people are expecting, ah… these people are expecting, ah… expecting something from me Monday. All right…

BD: I’m workin’, man. Like I’m buildin’ some shit, y’know? And I really gotta get it built. Just, you know, some tables and some shelves and some stuff, an’ I gotta get it done, man, I put it way off…

Dylan, the hen-pecked husband, unable to avoid that dreaded DIY session any longer!

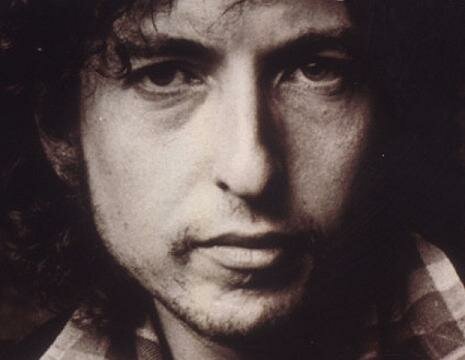

If an audio interview offers an extra dimension, this in itself is eclipsed by the experience of watching one on video. The footage of the KQED press conference, now officially available on DVD, represents an eternally cherishable, many-splendoured cultural artefact. Brow bound with swirling wreaths of cigarette smoke, helmeted in a shaggy tangle of hair, Dylan zestfully inhabits the role of inscrutable stoner Sphinx. Fizzing with nervous energy, he displays an astonishing parade of contradictions: he’s intensely uncomfortable but enjoying himself immensely; evasive but straight-talking; irritable but indulgent; arch but sincere; cool but warm-hearted; acerbic yet sweet. His relentless ‘put-ons’ are shot through with flashes of frivolously honest humour, and his charisma never wavers. That this footage still exists is a cause for rejoicing. Once seen, it renders written transcripts redundant.

Of course, it would be grossly unfair to criticise this collection for not being a multimedia experience; this is after all just meant to be a book. Instead, this anthology lays itself open to the much more damning accusation of inaccuracy, incompleteness, and sloppy editing. The widespread availability of these pieces, in a variety of forms, means that the savvy Dylan fan, or anyone else interested enough to check the original sources, will soon begin to notice some very significant omissions and discrepancies. There are far too many of these to list, but they’re evident right from the book’s very first interview, where we’re given a badly transcribed, cruelly truncated, and questionably edited version of that great period piece, Cynthia Gooding’s ‘Folksingers Choice’ radio interview.

The most egregious blunder is the misbegotten version of the KQED press conference transcript, which starts by omitting Ralph J Gleason’s introduction, and goes downhill from there. Gleason, who arranged and hosted the press conference, introduced Dylan with insouciant panache:

“Mr. Dylan is a poet. He will answer questions about everything from atomic science to, uh, riddles and rhymes. Go!”

Cutting that intro from the transcript may just be a bad judgement call. But it’s merely a prelude to a cascade of literally dozens of omissions, jumblings, misleading paraphrases and even outright inventions. Most shamefully of all, large chunks of the transcript have been cut out and re-inserted, seemingly at random, meaning the order has been totally scrambled. Presumably this has been done by mistake but it bespeaks incompetence spilling over into negligence. Wherever the editors sourced this transcript, could they not have at least checked it against the tape? This sort of sloppiness crops up everywhere, and utterly disqualifies this book from taking its place as a reliable source of Dylan interview transcripts.

A fascinating aspect of all this is that a number of the questionable edits and cuts affect parts of interviews which are directly relevant to media relations. Robert Shelton’s long-gestated Dylan biography, ‘No Direction Home’, has been much criticised over the years, often unfairly. Either way, one of Shelton’s many achievements was to get some unforgettably good conversation out of Dylan: no other author has managed to elicit such a perfect mix of the surreal and the sincere. One of the pieces collected here is actually an excerpt from a chapter of Shelton’s book, describing a conversation Shelton had with Dylan on a plane flying him (and The Band) from Nebraska to Denver, Colorado. This, one of the very best interviews Dylan has ever given, has been needlessly abridged here; ironically, the missing portion contains some sharp observations, from both Dylan and Shelton, on the role of the media. Dylan, Shelton is shrewd enough to note, is “one who has used the press with much artfulness.” Never a fan of journalists or critics, Dylan claims that “even before Dante’s time”, there was a special part of Hell reserved for critics:

“And when you think about it, it is very weird. Obviously, now, you see the ragman walking around a couple of thousand years B.C. and he did not like to be confronted by a bunch of mouths. That’s still where it’s at…”

Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner’s own interview with Dylan, from 1969, has been re-published and anthologised many times, often in a substantially restructured and oddly edited form. Again, some of the sections cut from this book’s version concern Dylan’s media relations, notably the part where he tells Wenner (during the course of an interview) that “I don’t do interviews”, because, “if you give one magazine an interview, then the other magazine wants an interview”, and then, “pretty soon, you’re in the interview business… You’re just giving interviews. Well, as you know, this can really get you down. Doing nothing but giving interviews.”

In fact, a comparison of the various versions of that one particular interview, and what the differences between them say about Wenner’s relationship with Dylan (and indeed, with pop culture in general), would make for an intriguing line of inquiry. For instance, the version presented here puts a curious gloss on an exchange which no doubt caused Wenner some embarrassment at the time, adding to Wenner’s reputation, in some quarters, for being a bit of a dilettantish flake. Wenner, feeling the interview is becoming awkward, suggests that the purpose of the interview process should be to let “the person who’s being interviewed unload his head.” Dylan starts to say, “Well, that’s what I’m doing”, then picks up on the expression ‘unload his head’, saying, “Boy, that’s a good… That’d be a great title for a song. Unload my head. Going down to the store… going down to the corner to unload my head. I’m gonna write that up when I get back.”

Now, it’s not impossible that Dylan genuinely didn’t twig, at that point, that he himself had used that very expression, on the ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ track, ‘For a Buick 6′ – “I need a dump truck, mama, to unload my head” – but if that is the case, it’s markedly uncharacteristic of his canny, suspicious attitude to the press. It seems more likely that he was putting Wenner on, which would be entirely in keeping not just with his usual modus operandi, but also with the rest of the interview. What’s really curious is that, in the original interview, after a few more questions, Wenner tells Dylan that the ‘unload your head’ expression comes from one of Dylan’s own songs, and Dylan asks which album that song was on (even though, elsewhere in the interview, he displays a clear-eyed grasp of which songs are on which albums). In the version printed in this collection, however, the intervening exchanges, between Dylan remarking on the phrase and Wenner informing him it’s Dylan’s own phrase, have been removed. The effect of which, intentional or otherwise, is to make it seem as though Wenner immediately realised that Dylan knew full well where the phrase came from.

Whatever the truth of the matter (and it would probably be a conspiracy theory too far to suspect Wenner of doctoring the transcript to make himself look less foolish), the interview, like this whole collection, struggles to transcend the stigma of the ‘Rolling Stone’ brand. If Dylan’s personality is riven with contradictions, and his attitude to the media characterised by ambivalence, few publications (or publishers) are worthier recipients of mixed feelings than Wenner and Rolling Stone.

Wenner began facing accusations of ‘selling out’ at least as early as the 1970s, long before the magazine became dominated by fawning puff pieces on bikini-clad celebrities, its pages bloated with endless glossy adverts for fancy cars and unnecessarily expensive liquors. Yet Rolling Stone was once a valid and even important part of the culture it was reporting on. This is, after all, the magazine which published classic, edgy material such as Hunter S Thompson’s ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’. Whatever the magazine has become, we should remember that at one time it was, as Michael Gray has put it, “(counter-) culturally relevant”. Leafing through a copy today, though, can be a dispiriting experience: its vibe feels smug, anodyne, and complacent.

For many readers, the Rolling Stone label, not to mention the ‘Wenner Books’ imprint which decorates the book’s spine, will stick in the throat a little bit. Sceptics of the magazine’s good intentions will have their worst preconceptions confirmed here: what is the point of reprinting a collection of previously published material, if you are going to treat that material so negligently as to compel the truly interested reader to return to the original sources?

The contemporaneous reader of an original 1960s Dylan interview would have been getting his dose of Dylan at a couple of removes: he’d be reading a newspaper or magazine account of an interview with someone who was in turn very deliberately presenting the interviewer with an already mediated version of himself. In this collection, the questionable handling of the original material adds yet another unwelcome layer of media obfuscation.

If there’s an obvious analogy between the difficulties faced by a compiler of a collection of Dylan’s music, and the editor of an interview anthology, then there’s also a parallel between the inadequacy of reading versus hearing a Dylan interview or lyric. Worst of all, there’s a correlation between how this collection has handled its versions of Dylan interviews, and the way in which Dylan’s music has often been questionably mixed and even cut. The classic example being early CD versions of ‘Blonde on Blonde’, which had some songs shortened – either by fading the endings out or even by cutting parts of harmonica solos, etc. – in order to force the album into a 72 minute running time.

The flaws of this particular collection aside, was there even any need for an anthology of Dylan interviews? The answer is a very definite yes; given the huge range of classic Dylan interviews, and factoring in all the additional post-millennial material, a new collection was very welcome. Like the famous horse photographs of Eadweard Muybridge, which used stop-motion technology to uncontestably prove that all four of a horse’s hooves did in fact leave the ground while it was on the trot, a chronological anthology of Dylan interviews resembles a series of snapshots which, viewed in sequence, offer a fascinating overview of everything that changed, and all that stayed the same, as Dylan’s relationship with the media (and with himself) evolved across the decades.

Sadly, one of the things that hasn’t changed is the general unreliability of media reports. The net result of all the edits, cuts, and omissions is that Rolling Stone’s ‘Essential Dylan Interviews’ falls far short of that ambitious title. Although this is not the first collection of Dylan interviews to be published, the editors of this book would not have had to work too hard to have made this one the best. If they’d widened their scope a bit, and taken care over the accuracy of what they printed, this could have been a truly essential purchase, not just for Dylan fans, but for anyone interested in the wider fields of pop culture and media relations.

And it’s worth restating: Jonathan Cott’s introduction is fascinating, insightful, and eclectic; in fact, it’s more worthy of re-reading than some of the interviews included here. Cott’s bona fides as a Dylan fan and scholar are not in question; his interviews with Dylan for Rolling Stone are some of the best ever conducted, and everything Cott himself writes about Dylan seems absolutely spot on: describing Dylan’s voice on ‘Time Out Of Mind’, for instance, as a “haunting timbral admixture of sandpaper and sherry”. Cott, incidentally, was an attendee of the KQED press conference (you can see him on the video). Most likely, Cott was not directly responsible for sourcing the versions of the interviews included in this book; whoever did that job for him has really let him down. It raises serious questions about how this sort of material will be presented to future generations.

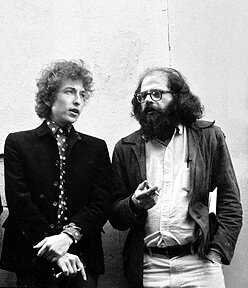

One day, when Dylan is gone, and the merry ontological dance he and the media led each other on has finally come to a permanent stop, Dylan’s legacy will doubtless take its proper place as an asset of the cultural heritage industry. Eventually, there’ll probably be a whole department of the Smithsonian devoted to him. The latest technology will be used to offer visitors an immersive glimpse into Dylan’s various phases and public images. Maybe there’ll even be an exhibit which recreates that classic 1965 KQED press conference, and, if you arrive early enough, you’ll manage to grab yourself a really plum seat – right next to the three-dimensional hologram of Alan Ginsberg, say. That should put you in prime position to revel in the irony of Ginsberg’s exchange with Dylan:

Ginsberg: “Have you found that the text of the interviews with you which have been published are accurate to the actual conversations?”

Dylan: “No.”

These interviews should have been the Dead Sea Scrolls of Dylan studies; instead, they’re more like the Turin Shroud. Some of the included interviews are indeed essential, yet many essential interviews are missing. Worse, the versions of the interviews which are included, are incomplete and unreliable.

If you’re not really interested in Dylan’s interviews, then you won’t ever need a book like this. If you really are interested, then this is not the book you need. On the other hand, if you’re interested in what Dylan’s collected interviews tell us about the process by which the media bring such interviews into being, and then present them to the public, then you will probably need this book plus the originally printed versions, to make your own comparisons.

Finally, some mention must be made of the fact that the best collections of reasonably accurate reproductions of Dylan interviews are the unofficial, bootleg anthologies which, though also available in print form, circulate freely around the internet as text files, PDFs, etc. (One such anthology runs to 1,390 pages – nearly three quarters of a million words – and it finishes with an appendix which lists 50 known interviews not included in its pages.)

Like many great Dylan songs, a given interview can exist in a number of forms, and it may not always be easy to determine which is the definitive version. This suggests yet another parallel with Dylan’s music: for every entry in the record company’s official ‘Bootleg Series’, there are any number of unofficial bootleg alternatives available, offering the Dylan fan the option of deciding for himself which is his definitive version.

In a sense, this is a fitting state of affairs, since it’s never been easy to measure the distance between the public and private Dylan(s). Discussing Dylan’s seeming ability, in his early Greenwich Village days, to alter his appearance from day to day, Jonathan Cott recalls “the advice once given by the Greek elegiac poet Theognis: ‘Present a different aspect of yourself to each of your friends… Follow the example of the octopus with its many coils which assumes the appearance of the stone to which it is going to cling. Attach yourself to one on one day and, another day, change color. Cleverness is more valuable than inflexibility.’”

Dylan’s shifting sense of identity, says Cott, brings to mind “the Buddhist notion that the ego isn’t an entity but rather a process in time.” For most people, ‘Bob Dylan’ is a kind of ‘process in time’: a mutable blend of voices, songs, images, and cultural signifiers, refracted through their own personal tastes and worldview. Each Dylan fan’s conception of Bob Dylan is their own unique version, and they wouldn’t want it any other way. If what you’re looking for, however, is ‘the real Bob Dylan’, then there are worse places you could trawl for clues than his vast corpus of published interviews. You might not arrive at any very definite answers, but you are guaranteed to have an interesting journey. As Bob Dylan himself would say: “Good luck. I hope you make it.”

<< Back to Part Two: Poets Drown in Lakes