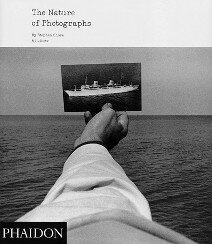

‘The Nature of Photographs: A Primer’

by Stephen Shore. Published by Phaidon Press Ltd; pp146; £14.95 (paperback)

by John Carvill

“Like an organism, photography was born whole. It is in our progressive discovery of it that its history lies.” – John Szarkowski

Discussing the tumultuous changes undergone by the art of photography during the 1970s, the BBC documentary series ‘The Genius of Photography’ recorded how “the biggest change of all came when some photographers began to see the world in a weird, new way: in colour.” That this statement was delivered with a faint twinge of humour wasn’t intended to diminish its essential seriousness. It may seem strange in retrospect, but up until the late Seventies, colour photography had been considered suitable only for amateur snapshots, or as a palette for indulging in crass commercialism; the colour of art photography had always been black and white. When this convention was abandoned, the effect was cataclysmic. As the BBC’s narrator put it: “At the time, colour photography was as shocking as Dylan going electric.”

Wide-ranging yet finely-detailed, ‘The Genius of Photography’ series was remarkable in a number of ways. For one thing, there was the simple fact that it was a six hour television series about photography. Here were two modern, still-evolving, related but very different mediums, one being used to examine the other. That was the big picture. At a more immediate level, one of its biggest draws lay in offering viewers the opportunity of seeing famous photographers at work and in conversation. Here is Stephen Shore, in the episode entitled ‘Paper Movies’, describing the Damascene moment when he first began to question the artistic superiority of black and white over colour photography:

“I had met someone at a party in New York. And we got to talking and he asked what I did, and I said I was a photographer. And he said, ‘Oh, can I see your pictures?’ And I opened a box, and as soon as I opened the box he said, ‘Oh, they’re in black and white.’ And he really… wasn’t exposed to art photography. And that impressed me, that he was expecting, when I opened the box, he was expecting to see a colour photograph. And it shocked him that it was black and white and I thought, ‘What is this? What’s this convention about?’”

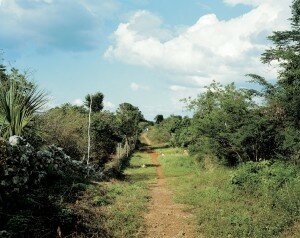

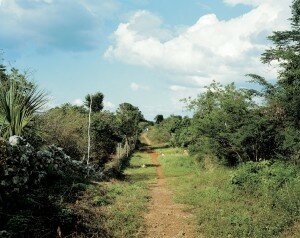

One of the key photographers at the vanguard of the colour revolution, Stephen Shore was also central to the development of the evocatively-named ‘new topographics’ movement, producing images that photographic historian Naomi Rosenblum has defined as presenting “the artifacts and landscapes of contemporary industrial culture without emotional shading.” These revolutions were concurrent, not consecutive; they were also influential on each other. Many practitioners of the ‘new topographics’ worked in black and white, but Shore used colour, which added another dimension to his work. “The color in Stephen Shore’s depictions of city streets and buildings throughout the United States”, wrote Naomi Rosenblum, “lends these banal entities a degree of interest that would otherwise be lacking.”

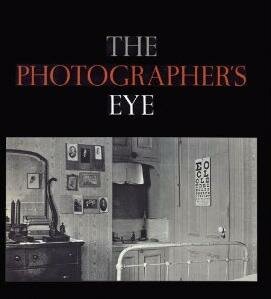

Shore had always been prodigious. In his early teens, he was already taking such impressive photographs that he managed to sell a few of them to Edward Steichen, Director of Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In 1964, Steichen’s successor, John Szarkowski, oversaw a landmark photography exhibition, documented in his book, ‘The Photographer’s Eye’, first published in 1966. When Shore began teaching a photography course at Bard College in 1982, Szarkowski’s hugely influential book became a key text for his classes.

Broadly speaking, ‘The Nature of Photographs’ can be considered a sort of sequel to, or maybe an iteration of, ‘The Photographer’s Eye’. Certainly the two books have much in common, in terms of both format and sensibility. Szarkowski called his book “an investigation of what photographs look like, and of why they look that way”, a consideration of “the history of the medium in terms of photographers’ progressive awareness of characteristics and problems that have seemed inherent in the medium.” Shore’s book explores various “ways of understanding the nature of photographs”, investigating the qualities which “determine how the world in front of the camera is transformed into a photograph.”

Szarkowski identified five key ‘issues’: ‘The Thing Itself’, ‘The Detail’, ‘The Frame’, ‘Time’, and ‘Vantage Point’; Shore explores a number of ‘levels’ on which a photograph can be viewed: ‘The Physical Level’, ‘The Depictive Level’, and ‘The Mental Level’. Szarkowski said his five ‘issues’ should “be regarded as interdependent aspects of a single problem – as section views through the body of photographic tradition.” Shore’s overall approach is similar; the difference, you could say, is just that the sectional views he provides are differently angled. And in a number of cases – as when Shore subdivides the Depictive level into four categories – ‘Flatness’, ‘Frame’, ‘Time’, and ‘Focus’ – those angles begin to intersect.

Shore’s photographs are often described as ‘banal’, but it would be more accurate to say that the basic subject matter of these images consists of mundane scenes, which are rendered interesting through the agency of photographic vision. By the same token, some of the wider points in ‘The Photographer’s Eye’ may initially appear to be fairly self-evident. Consider the following statements:

“As an object, a photograph has its own life in the world. It can be saved in a shoebox or in a museum.”

“The world is three-dimensional; a photographic image is two-dimensional.”

“A photograph is static, but the world flows in time.”

Obvious, right? Yes, but only in the ‘obvious once you’ve said it’ sense. How often, for example, do we actually think of ‘a photograph’ as a physical object? There are also plenty of statements which, though very simply put, are of far-from-obvious import. Shore being Shore, many of these relate to colour: a colour photograph is, for instance, “more transparent because one is stopped less by surface – colour is more like how we see.” In any case, these basic statements are merely the initial links in chains of thought which become increasingly abstract and less obvious as they progress. (Lest these seemingly simplistic points lull you into a false sense of complacency, bear in mind that you’ll soon be parsing stuff like this: “A photograph may have a relatively uninflected structure but have recessive mental space.”)

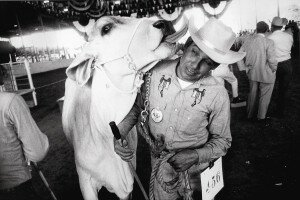

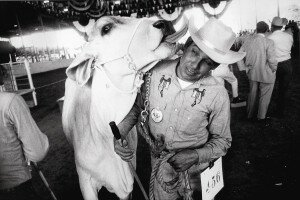

Shore’s highly effective, occasionally humorous use of illustrative examples helps to keep the book from ever seeming over-serious or po-faced. Having established the premise, for instance, that photographs are static whereas the world is in flux, Shore goes on analyse how “a new meaning, a photographic meaning, is delineated” when the flow of time “is interrupted by the photograph”, using a characteristically idiosyncratic Garry Winogrand image to reinforce his theme:

“Amid the flux of all this motion”, Shore writes, “there was one instant, one two hundredth and fiftieth of a second, when seen from a single vantage point and recorded on a static piece of film, the steer’s tongue and the brim of his handler’s Stetson met in perfect symmetry; an instant that, as quickly as it arose, dissolved back into disorder.”

To demonstrate the fact that photographs have “monocular vision – one definite vantage point”, and that “when three-dimensional space is projected monocularly on to a plane, relationships are created that did not exist before the picture was taken”, Shore uses a Lee Friedlander photograph in which the back of a ‘give way’ sign in the foreground, and a cloud formation in the distance, have combined to suggest an ice cream cone:

Although Shore often uses just one image to illustrate a given point, there are many instances where, having outlined a concept, he then lays out a sequence of un-annotated photographs to demonstrate it (or, rather, to investigate it), leaving the reader to ponder how the images relate to what’s been said. After making the point that colour photography has the ability to show “the colours of a culture or an age”, he specifically mentions a particular photograph which, although taken in the late 1980s, has very deliberately used a colour palette which makes it look like it was taken in 1960. There then follows a succession of colour photographs, upon which Shore makes no comment, leaving you to consider how colour has been used in each. The result is the perceptional equivalent of a father slowly taking his hand off the seat of his son’s first bicycle, and letting the child wobble along on his own. The aim is to show, rather than tell. It turns the book into a kind of portable mini-gym for the mind’s eye.

Shore’s levels – Physical, Depictive, Mental – often interact and combine to cumulative effect. “Each level of a photograph is determined by attributes of the previous level”, each “provides the foundation the next level builds upon.” While the mental level “is separate from the depictive level, it is honed by formal decisions on that level”. Thus, in Thomas Annan’s quietly sinister photograph of a Saltmarket close, the photographer has focused on “the black void at the end of this impossibly narrow ally”, drawing “our mental focus through the confined space of the image. Focus is a bridge between the mental and depictive levels: focus of the lens, focus of the eye, focus of attention, focus of the mind.”

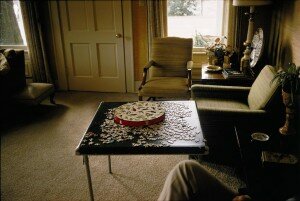

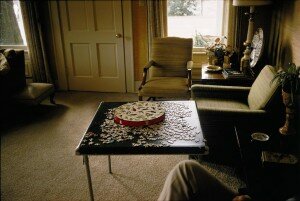

One of the book’s most fascinating deliberations is based around an image that isn’t actually a photograph: to illustrate the fact that the frame of a photograph “can be active or passive”, Shore discusses a Japanese woodblock print, in which stray parts of extraneous figures are visible at the corners of the frame. His passion for his subject is powerfully felt in his enthusiastic recognition that “it really is amazing that the artist chose to add” a “leg jutting into the image from the lower right” corner, when, this being a constructed image, rather than a photograph, it was not the case that the leg was just ‘there’ and could not be excluded. It is the very fact that the artist has deliberately included the seemingly superfluous leg that makes Shore’s point: the leg “doesn’t relate to the unfolding drama of the picture”, but it “does imply that this drama is part of a larger world.” We are reminded of this later in the book, when we see the knee (and some knuckles) of a seated person protruding into the bottom of an otherwise unpopulated William Eggleston photograph.

A casual flick through this book might give the impression that it doesn’t have a lot to say – there doesn’t seem to be much text. Again, this would be deceptive. It’s true that the word-count is relatively low; but Shore’s finely honed prose is epigrammatically concise. Contrasting the different types of compositional decisions required of painters and photographers, he writes: “The artist starts with a blank page and must fill it. The photographer starts with the clutter of the world and must simplify it.” Shore brings a master photographer’s decluttering skills to bear on his text, making his points with concision and verve. Throughout the book, the style is laconic and occasionally poetic; the tone is contemplative going on philosophical. The photographic image, says Shore, “turns a piece of paper into a seductive illusion or a moment of truth and beauty.”

Towards the end of the book, Shore offers this meditative proclamation on the subject of ‘mental modelling’:

“Earlier I suggested that you become aware of the space between you and the page in this book. That caused an alteration of your mental model. You can add to this awareness by being mindful, right now, of yourself sitting in your chair, its back pressing against your spine. To this you can add an awareness of the sounds in your room. And all the while, as your awareness is shifting and your mental model is metamorphosing, you are reading this book, seeing these words – these words, which are only ink on paper, the ink depicting a series of funny little symbols whose meaning is conveyed on the mental level. And all the while, as your framework of understanding shifts, you continue to read and to contemplate the nature of photographs.”

In a snippet of an interview from the ‘Genius of Photography’ series, Shore recalled the genesis of his ‘banal’ images of the everyday American landscape:

“What I wanted to do was to keep a visual diary of the trip and started photographing every person I met, the beds I slept in, the toilets I used, art on walls, every meal I ate, store windows, residential buildings, commercial buildings, main streets and then anything else that came my way and that became the framework for that series. I drove in rental cars and I don’t think that they had tape decks at that point so it was just ‘Top 40′ radio or whatever the local radio station was, religious stations, country and western stations. Sometimes, to entertain myself, I would recite Shakespeare and, after a couple of days, I entered a very different psychological state.”

‘The Nature of Photographs’ is a work with the potential to radically alter the reader’s psychological state. It’s of great significance that the book’s very first sentence is a question. It is designed to make think. If it doesn’t provide you with at least some food for thought, then you must be on hunger strike. Do yourself, and your understanding of the nature of photographs, a favour: buy it.