by Steve Mainprize

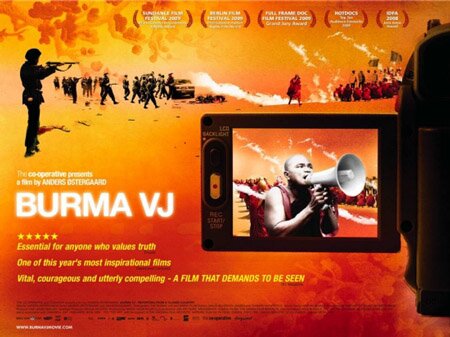

On 7th November 2010, elections are due to be held in Burma, the second-largest country in South-East Asia. These are the first elections to be held in the country since 1990, so it seems a good time to finally catch up with ‘Burma VJ’, Anders Østergaard’s Oscar-nominated documentary.

A bit of background: since 1962, the Burmese military has been in control of the country following a coup d’état led by General Ne Win. Between 1962 and 1988, Burma declined spectacularly and became one of the poorest countries in the world, thanks to a combination of economic isolation, Soviet-style central planning policies and official government policy based on superstitious belief.

1988 saw widespread pro-democracy protests throughout the country. Eventually, the army was deployed to subdue the protesters; an estimated 3,000 people were killed.

The 1990 elections were comfortably won by the National League for Democracy, but the military junta refused to accept the result and retained power. The NLD’s leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, who was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts to restore democracy to the country, was placed under house arrest (where she remains today).

In 2007, the government suddenly withdrew fuel subsidies, leading to sporadic protests which were quickly put down by the authorities. Then the country’s Buddhist monks began to protest, which the government found harder (culturally) to deal with. The monks were soon joined on the streets by ordinary Burmese people. Although the outcome of the 1988 uprising was not forgotten, the people were encouraged by the monks’ success, and joined the protests. It’s these 2007 events that are covered by ‘Burma VJ’.

‘VJ’ stands for “video journalist”. The film focuses on a guerilla video journalist referred to only as “Joshua”, a member of the Democratic Voice of Burma: the DVB is an underground media organisation whose objective is to expose the reality of life under the Burmese military regime. Their footage is smuggled out of the country, and has found its way onto CNN, the BBC and many other media outlets, particularly during the 2007 protests. It’s also beamed back into Burma on pirate TV stations. The DVB’s audience is not only the outside world, but – as a counterpoint to the regime’s propaganda – the Burmese people themselves.

The film is pieced together from footage surreptitiously (and often illegally) shot by the DVB’s reporters. We’re told in the film’s opening caption that “some elements of the film have been re-constructed in close co-operation with the actual persons involved, just as some names, places and other recognizable facts have been altered for security reasons in order to protect individuals”, but the degree to which reconstruction has been used is not revealed; we are not always sure whether what we’re watching is real.

Sometimes you (think that you) can tell a scene has been reconstructed because of the quality of the footage, or the way the shot is framed. Other times, for instance in the scenes that document thousands of people marching through the streets of Rangoon, there’s no way it could be a reconstruction. There’s a scene in which the country’s Buddhist monks are joined by ever-increasing numbers of citizens. People are hanging out of the windows of city buildings and lining the rooftops to cheer on the marchers. A man walks towards the camera and points up, shouting “Film them! Film them all!” It’s very emotional: uplifting, and tragic if you know how it’s all going to end, and there’s no way it’s faked.

Where the spectre of reconstruction is a problem is in the scenes in which the veracity is not so clear-cut. In one scene, a protester is snatched by plain-clothes security forces. The security forces attempt to throw her into the back of a truck, while protesters fight to rescue her. Is it real? The fighting seems diffident, but then again, real street scraps can be like that. The dialogue seems stilted, but we’re getting it in translation via subtitles, so who knows?

Why it’s a problem isn’t really to do with whether or not we believe what we’re being told is the truth. What’s going on in Burma isn’t seriously up for debate; the brutal events of ‘Burma VJ’ are corroborated and condemned by media organisations from the Guardian to Fox News. Even if there were a debate, we’re used to documentary makers taking a stand – it’s the legacy of Michael Moore, of ‘Bowling For Columbine’, ‘Fahrenheit 9/11’, and of others.

In any case, it seems only reasonable to obfuscate some of the details surrounding “Joshua”, his colleagues in the DVB, and their subjects, for the sake of their personal security. It’s also reasonable for the sake of story. If a particular scene would make the narrative work more elegantly, but no footage exists, I see no real problem with shooting a reconstruction of that scene. An example would be the framing sequences in which “Joshua”, in hiding in Thailand, uses his cell-phone and computer to liaise with his DVB colleagues back home in Burma. There would have been no reason for “Joshua”, ostensibly alone, to film these scenes, but they work to provide context and move the narrative on.

The problem is that it’s frequently distracting trying to discern what’s real and what’s not. It gives the viewer something else to think about, when he or she should be considering the wider and more important issue of the plight of the Burmese people. Use of a caption to indicate which scenes were real and which were not would surely have been simple, so you do find yourself asking why they didn’t do that.

Such distractions apart, ‘Burma VJ’ is a convincing and emotional film, and an important one. There’s no happy ending to this film, and it’s a draining experience, particularly if you know where it’s leading. I’ve seen it twice, and watching the second time, I was most affected by the contrast between the peacefulness of the demonstrations and the brutal resolution to come. The protests may be amongst the largest you will ever see – a seemingly never-ending sea of people – but also, as befits a protest led by Buddhists, the least angry and the most reasonable. “We demand a dialogue!” and “Reconciliation now!” are the slogans most often heard. This merely makes the downbeat ending more tragic. The violent quelling of the protests is a matter of historical record, so what follows are not spoilers as such: the film ends with monks subdued by the army with extreme prejudice, and members of the DVB scattered or imprisoned.

The final scene takes place a year later, in the wake of Cyclone Nargis. It consists of more guerilla video footage, this time of interviews of cyclone survivors, victims of not only natural forces but of their own government’s indifference. The government’s isolationist policies prevented international aid from arriving and an estimated 140,000 people ultimately died.

Go and watch ‘Burma VJ’ at Channel 4′s web site, and consider your own good fortune.

[...] in 2007 when Buddhist monks led protests against the military. It just so happens I also read a review on oomska of the film Burma VJ today too, this film covers those protests. So I thought to mark this occasion [...]