Oomska’s ‘Future of Photography’ Series continues…

We presented our interviewees with a set list of questions, and left the matter of in what format and at what length they should answer entirely up to them. Here are Nick Turpin’s responses.

1. How and when did you first become interested in photography? What was the trigger which led you to take a serious interest? How different would that trigger be now, with all the changes – technological and otherwise – in photography during the intervening years?

My father introduced me to photography when I was a teenager, still at school, he built a darkroom for me in our second toilet at home. I went on to specialise in photography on my foundation course for a year then moved to London to do a BA in Photography, Film and Video at The University of Westminster. In my second year I shot two black and white stories, one about children with Leukaemia living around the Nuclear Reprocessing Plant at Sellafield in Cumbria and one about the closure of the coal mine in the village of Aberfan in South Wales where a generation of children was lost in a landslide in 1966. I showed this work to the Picture Editor of the Independent Newspaper and ended up quitting my course to be a press photographer, I was 20 and had been taking pictures for just three and half years.

So my entry into professional photography was extremely rapid, I didn’t even really have time to think about what I wanted to do with the medium until much later. In a way I was working as a photographer daily for a number of years before I really discovered and came to understand it’s unique quality and power. It was when I eventually understood what photography could do that I left the Independent Newspaper in order to pursue it, that was seven years later.

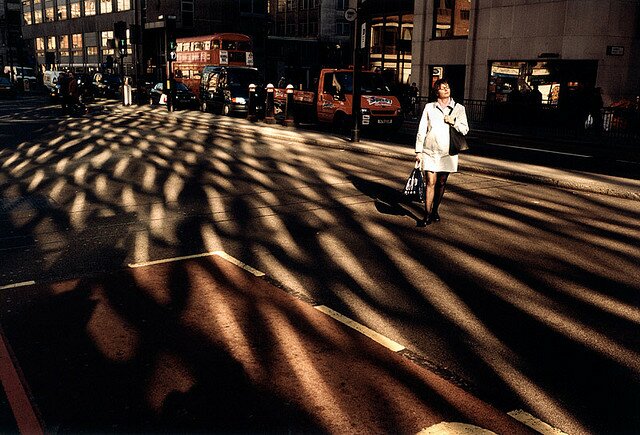

‘Fallen Man, Paris, France 1967′ by Joel Meyerowitz is a photograph that I saw first in the college library and then later in the Street Photography book ‘Bystander’, this picture was enormously significant for me because it was the most extraordinary frozen moment of life and showed me how ‘revelatory’ the process of photographing could be. How could you even begin to set out to take a photograph like that? It was so exciting, I knew that was the kind of picture I wanted to make and I knew if I did, I would be working right in the sweet spot of the medium, utilising exactly what the camera does best.

Many lament the passing of film and criticise the digital camera but for me this is nostalgic nonsense, the digital camera is an enormous bonus for Street Photographers like myself who can pursue elusive moments endlessly with little real cost. I shoot a lot and I like to work that way, it allows for wonderful accidents and unique ‘untakeable’ photographs.

2. Photography is often described as a mixture of art and science. It’s also a medium. How has digital technology altered the way these elements combine to produce what we think of as ‘photography’? Has technology altered that balance?

Sure, Photography is a blend of the artistic and the technical, that’s always been the case and remains so, I don’t think digital cameras have really changed anything apart from removing the complexities of the chemical darkroom.

The prolific use of Photoshop has certainly changed the scene and created an environment where one doubts the veracity of every image one sees but in a way I see that as a wonderful thing for us Street Photographers, it sets us apart from most other genres because you can’t push a button or apply a filter to achieve what we achieve with the camera, you can’t Photoshop a remarkable unimagined moment… it makes what we do increasingly special, that’s why I consider good Street Photographers to be among the best photographers, full stop.

3. Prior to the introduction of digital, how much did the equipment you used change over the years? How has digital changed the way you use equipment? How would today’s technology, if you could have used it earlier, have changed your relationship with photography?

You are asking the wrong photographer when it comes to equipment, my work doesn’t rely on that very much, OK I use an expensive Leica M9 but I could just as easily take my pictures on a phone and in fact I have done so all around the world for Samsung. My tools are my patience, instinct, experience and sense of observation, the camera is crucial to record the scene but seeing the scene is what Street Photography is really about.

4. How would photography’s great pioneers have embraced and utilised today’s technology? Might Ansel Adams be using software to stitch together panoramas of Yosemite? Would Garry Winogrand be using an iPhone? Would Eadweard Muybridge be experimenting with HDR?

I think the great photographers would have grasped today’s technology in the same way that they grasped the technology of their day, I’m quite certain Garry Winogrand would have loved the digital Leica but only in as far as it would have ‘enabled’ him to achieve his goals. This is why I am keen to use the technology available to me to make pictures that are different to Cartier Bresson’s images with the first film Leica. The large sensors of today’s digital cameras allow me to make much bigger, more crowded and busy Street Photographs because of the detail they can hold and render, it’s something I very much enjoy using.

5. In some ways, digital seems to have ‘won out’ over film. Digital photography is everywhere, while companies such as Nikon and Fuji are discontinuing some of their films and film cameras. Is this process irreversible? Should we care?

Digital cameras are only on one path and that is to supersede the qualities of film in every aspect, we may not be there quite yet but it’s coming. Some people enjoyed the craft of film, contact sheets and printing but for me the only concern is the image that captures the moment and film is certainly not central to that goal.

6. Are there some qualities or aspects of film photography which digital will never be able to replicate or replace? If so, will these aspects of photography die with film?

I think tonally, film still has the edge over digital but digital wins hands down when it comes to rendering detail, if you are shooting beauty or maybe some kinds of landscape you may want to continue on film but I think the nostalgia for film will decline with future generations.

7. Will the ‘camera’, as we (still) think of it, even remain as a distinct device? Or will ‘camera’ become just one of a plethora of multimedia features people expect to find on any number of hybrid consumer appliances?

I am sure that cameras will continue their integration into many other devices, that is the converging direction many areas are taking, phones, music, radio, TV etc. are all becoming miniature and mobile. I don’t think we should be too concerned by these developments, ideas and their execution will still remain at the heart of the best photography whatever the recording device ends up looking like.

8. A few years back, Magnum photographer Eliott Erwitt was quoted as saying: “Digital manipulation kills photography. It’s enemy number one.” He also disdained digital in general, for its ability to produce “an image without effort”. To what extent would you agree or disagree with these sentiments?

I think the arrival of Photoshop and its ubiquitous use has led to a situation where we cannot rely on the veracity of a photographic image and for documentary photographers who ‘record’ that is a problem and I think that is what Elliot Erwitt was referring to. I am only upset by manipulation when it is hidden and unannounced, to present a manipulated or comped image as a genuine record of a scene or happening is the worst photographic crime in my book and I know that organisations like The World Press Photo awards feel the same way by the way they have treated offenders in the past.

In terms of digital photography allowing you to make ‘an image without effort’ I don’t agree with that, to replace the film with a sensor does not make any difference to the effort required to make a good photograph, maybe the fact that you have 1,000 images to play with on a memory card compared to the 36 on a roll of film can create a different way of shooting where each frame is expended with less consideration, but I think that is a matter for the photographer and his own sense of self control. I personally find the advantages of working on the street with a digital camera far outweigh the disadvantages, least of all the fantastic print quality achievable at the end of the process.

Digital has certainly freed up my street photography in many ways.

9. We’re all thoroughly weary of the ‘fix it in Photoshop’ approach. But defenders of digital post-processing often say, “Well, it only does what you used to do in the darkroom.” Is this a valid argument?

Photoshop is capable of going far beyond what we used to do in the darkroom and many images we see today I would consider to be photo illustrations rather than photographs, the image is drawn by hand not by light.

There has been a trend in recent years to comp images of the street, photographers like Peter Funch, Pelle Cass and Schinster make images composited in Photoshop but, although time consuming, I consider these images easy to make compared to the process of creating a genuinely extraordinary moment from the street, they are as much a tribute to the engineers at Adobe as they are to the skills of the photographer. Where is the challenge, the relevance or the meaning in these images? I actually feel the same way about staged narrative photography, it amuses me that photographers consider it a great artistic endeavour to create a picture that looks like a moment of reality but is actually made with models and stylists and lights… it was interesting when Jeff Wall did it for the first time but quite boring to see it repeated for a decade by a series of Art Photography graduates.

10. For how much longer will the general conception of ‘photography’ refer exclusively to static, two-dimensional images? Imminently, 3D is looming, and ‘convergence’ – meaning not just the ability of modern DSLR’s to capture high-definition video, but the compulsion to make use of that functionality – is a current buzzword. Does this trend – photographers becoming film-makers, and vice versa – ignore the important divisions between static and moving images?

I think the camera has a fantastic trick, it can freeze a fleeting busy passing moment from a three dimensional world and record it forever in a two dimensional form that we can hold and inspect in all its detailed frozen glory for as long as we like, it has a poignance and poetry that moving image is totally incapable of. Having said that, the medium of moving image lends itself to storytelling and narrative communication in a way that eclipses that of stills. It is very much a matter of choosing the right tool for the right job. Having DSLR’s that allow us to create either stills or moving image is a fabulous opportunity and one that I have certainly grasped with both hands. My very first film in-sight was shown at Tate Modern this year and is available to stream and download online, that is very exciting but it doesn’t detract from my ultimate fascination with the power of the still image.

I am very sceptical about 3D, maybe when we don’t have to wear daft glasses it could be adopted seriously.

11. Cinema historian David Thomson, in his ‘Biographical Dictionary of Film’, wrote the following, regarding Marilyn Monroe: “She gave great still. She is funnier in stills, sexier, more mysterious, and protected against being. And still pictures may yet triumph over movies in the history of media. For stills are more available to the imagination.” How much more of a contentious statement does that seem today?

Still photographs by their nature will always be hugely ambiguous, they maintain a strong relationship with the real scene or happening they were created from but always leave a lot to be interpreted by the viewer and his/her copious cultural baggage. I’m not sure that situation has changed much since David Thomson talked about stills of Marilyn, I imagine the selection of individual frames from the many taken at a shoot with Marilyn would lead to only the ‘sexiest, more mysterious’ ones being seen, the ones of her blowing her nose were presumably edited out. In comparison the under-edited stream of images that is moving image is always likely to be more ‘warts and all’ and lend itself less to becoming iconified.

Nick Turpin was born in London, UK in 1969. He studied ‘Art and Design’ at the University of Gloucestershire then ‘Photography, Film and Video’ at the University of Westminster until 1990 when he left to work as a staff photographer with The Independent Newspaper leaving in 1997 to pursue a second career in Advertising and Design photography. In 2000 Nick was the founder of the international street photographers group in-public and in 2010 he established Nick Turpin Publishing. Nick has also taught and lectured on contemporary street photography at Museums, Universities and on TV.

[...] >> Go to Part 9 – Nick Turpin Q&A [...]