The Phantom Ride: Early Cinema and The Train

by Brian Phelan

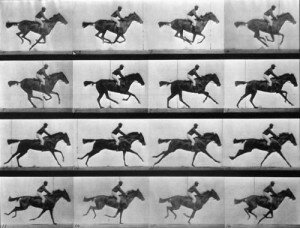

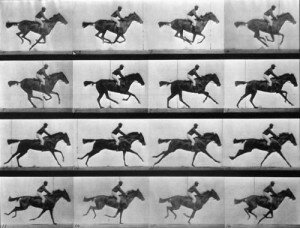

Before there was cinema, there was the train. It might seem fanciful but I’d like to make the claim that train travel not only prepared people for the idea of cinema but may even have been a catalyst for its eventual creation. Invention is such a mystery, after all, something in the air of the times, a whisper of influences waiting to coalesce. Surely the idea that still images could move was born in the mind of someone sitting by a train window watching the world go by, or millions of people sitting by thousands of train windows watching endless fields and suburbs go by. It was in the air. Cinema the idea was already an invention of the imagination long before science and technology caught up. This was the era of camera obscura towers, magic lantern shows and experiments in capturing the secrets of motion by men like Eadweard Muybridge and Jules Maray. Cinema was the culmination of all these processes, all these primitive yearning mechanisms for capturing life.

The wonder of early cinema wasn’t in stories or acting or montage; it was just this: the mystery of suspended time, of captured motion. Just like train travel. Who, after all, hasn’t been lulled into a time-forgetting dream-state by the clickity-clack rhythms of a train, the rolling cinema of carriage windows? The analogy was there from the start. They were kindred spirits, both symbols of progress, both promising journeys to other places, both foreshortening distance and time in ways society had never imagined before.

And so, naturally, it was to the train that the earliest filmmakers were drawn again and again, in homage and unconscious recognition. Between those famous train-centred milestones of early cinema, the Lumiere Bros’ panic-inducing L’Arrivée d’un train à La Ciotat (1896) and Edwin S. Porter’s narrative breakthrough The Great Train Robbery (1903) lies a generally less well-known period of sensation, novelty and gradual evolution, when techniques were discovered that are still with us today. And one of the most popular and profound of these was the phantom ride, an evolutionary step forward for the fledgling medium, one in which it stopped simply recording motion and instead

became motion itself.

In the typically cavalier fashion of the times the effect was achieved by tying a cameraman to the buffer of a moving train and having him crank away as it sped along the track. The means may have been primitive, not to mention dangerous, but the result was a sensation, a ghostly ride through the air, as if the viewer were floating above the track, a disembodied dream eye travelling into the darkness of tunnels and towards the light on the other side.

Audiences couldn’t get enough of these virtual thrill rides which were often, appropriately enough, shown at travelling fairgrounds as part of a programme of similarly short actualities, comedies and trick-films. The earliest known example, Biograph’s The Haverstraw Tunnel (1897), was an instant hit, spawning dozens of imitators including Railway Trip Over The Tay Bridge (1897), View From An Engine Front – Ilfracombe (1898) and View From an Engine Front – Train Leaving Tunnel (1899). The latter was used by one of the most innovative filmmakers of the time, G.A. Smith, to create his influential A Kiss In The Tunnel (1899). It consists of only three shots: train enters tunnel, man kisses woman in the dark compartment, train exits tunnel. It might not sound like much now but this was a major advance in editing and continuity, leading the medium towards more sophisticated story-telling.

Although single-shot phantom rides continued after this, well into the new century, taking in ever more exotic and far-flung places from the front of ships and trams as well as subway trains, it was soon just another technique in an ever-expanding arsenal of possibilities. The success of The Great Train Robbery had marked the end of simple awe and curiosity and the start of cinema as a serious art form with all the potential range of novels and theatre.

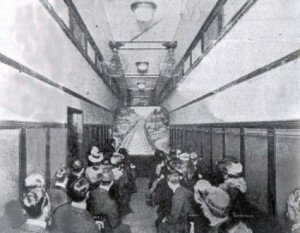

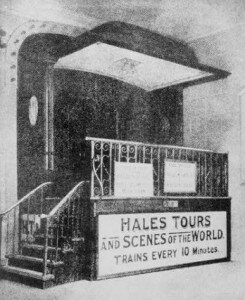

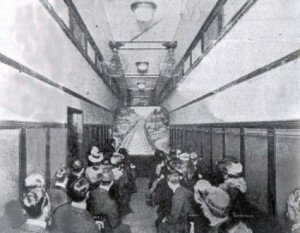

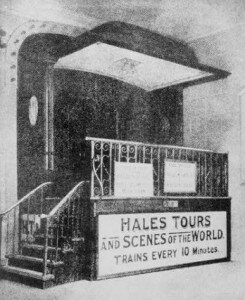

But there was to be one final hurrah for the pure phantom ride form, one which brought the relationship between trains and films to its logical conclusion. In 1905 a Kansas City Fire Chief named George C. Hale created a nickelodeon amusement called Hale’s Tours and Scenes of the World. This ‘illusion ride’ consisted of mock train carriages showing ten-minute films of scenes from around the world. But they weren’t just novelty cinemas. While the passengers watched these phantom ride films, projected onto the end of the carriage to create the illusion of actually travelling through these scenes, like they were looking through a window, the carriage would simulate the motion of a real train, rocking and swaying from side to side while steam and train whistle sound effects played and painted scenery rolled past the windows.

The Hale’s Tour had finally made real what had always been implied; that being in a train and watching a film were essentially the same thing, that illusion and travel worked on the imagination in much the same way, creating intermediary zones away from the real world where people could dream and forget. Not surprisingly, they proved insanely popular. By 1907 there were five hundred all over the United States, and many more around the world in places like Paris, Hong Kong and London, which had no less than four, with others in Manchester, Blackpool, Leeds and Bristol.

Despite this success, the truth was the phantom ride had effectively been shunted onto a siding of cinema history, merely a passing fad, a necessary but primitive first step in the maturity of a great new art form. And watching the surviving examples today it’s easy to dismiss these grainy, ponderously slow artefacts, to wonder how they could ever have had such an electrifying effect on audiences. But speed is relative and what would have given a Victorian a nosebleed barely feels like moving now. In 1962 a British Transport documentary called Let’s Go To Birmingham revived the form to record the journey from London’s Paddington Station to Birmingham’s Snow Hill but with one crucial difference, they speeded it up so the entire journey takes only five minutes. It’s still a blast and is probably a modern viewer’s best chance at understanding what it was like to see the first phantom rides.

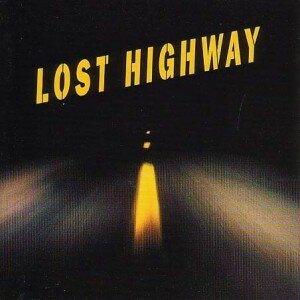

Today the phantom ride has become a standard cinematic device for putting audiences into the heart of the action, little different at times to its thrill ride origins (note its use in the current 3D craze, like the rollercoaster scene in Despicable Me for example). But it’s also been used for the opening title sequences of films like Get Carter (1971), The Warriors (1979) and David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1996), not just as a way to create an immediate sense of momentum and excitement but also to put us in the right frame of mind for the film to come, to lure us into the disembodied dream-state of film itself. One phantom ride, you could say, preparing us for another.