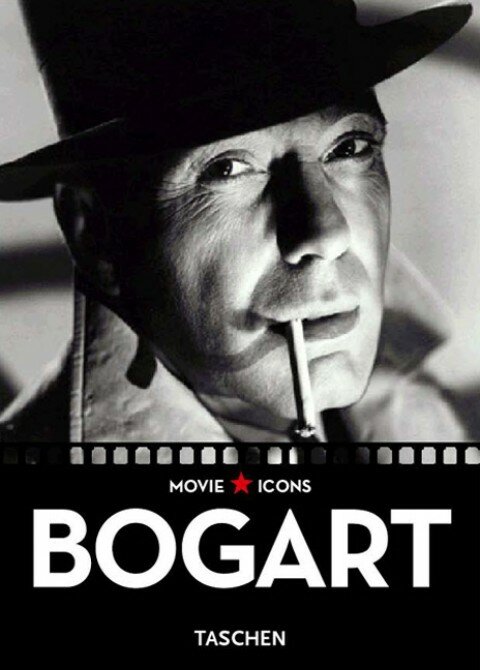

Taschen’s ‘Movie Icons’ series offers a chance to ponder the particularities of iconic movie stills.

“She gave great still. She is funnier in stills, sexier, more mysterious, and protected against being. And still pictures may yet triumph over movies in the history of media. For stills are more available to the imagination.”

- David Thomson on Marilyn Monroe

In the olden days of the Hollywood dream factory, when movie stars were doggedly elusive and – not coincidentally – infinitely more interesting, the big Studios rigorously controlled access to their stars, radically adjusting their accessibility levels according to context: on one side, no press people got any kind of unmediated access to the likes of Bogart or Gable – the Studios controlled and choreographed all such encounters; at the same time, stars were made to make themselves available for publicity duties at the behest of the moguls who called the shots. Studio publicity departments were adroit at image-massaging machinations. If a male star, say, was the subject of rumours which threatened to undermine his perceived heterosexuality, then a suitable starlet would be lined up to publicly accompany him to a première or party, acting as a twinkly-eyed beard. It was the age of the ‘publicity still’. Elaborate tableaux were constructed into which the compliant actors were expected to step at the last moment, to have their photographs taken surrounded by suitably image-reinforcing paraphernalia. The resultant shots were at once utterly disconnected from the actors’ presence in their films, yet also somehow of a piece with their existence as ‘stars’.

Today, we’re more used to seeing ‘stills’ from movies used as publicity, usually the same one or two for a given film, repeated endlessly across all media outlets, often accompanied by a notice which isn’t much more than a half-hearted rewrite of the blurb the studio has issued to press junket attendees. We don’t much see the traditional-style publicity stills any more. Instead, we’re accustomed to being ‘invited’ into stars’ beautiful homes via lavish but culturally vacuous magazine spreads. They used to say that a picture is worth a thousand words; that assessment was arrived at in a more innocent time, long before we all got used to having our minds boggled by reports that the rights to candid photos of Brad and Angelina’s offspring were worth X million dollars to celebrity magazines. That sort of thing makes the golden days of Hollywood seem even more distant than they are; as Bob Dylan once put it: “Seems like a long time ago, long before the stars were torn down…”

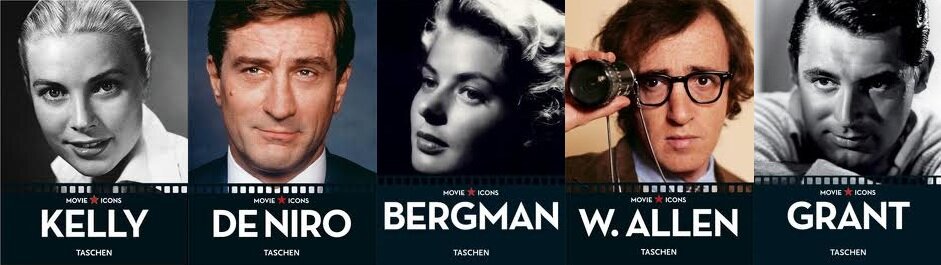

Each entry in Taschen’s ‘Movie Icons’ photo book series – introduced in 2006 and now running to 22 titles – focuses on a given big-name star, employing a mixture of publicity shots and movie stills to pictorially depict that actor’s progress through both their career and our fascination with them, or at least with their image and its cultural associations. There’s an enormous amount that could be said about this fascination, and even more on the piquant yet amorphous nature of the dynamic between movies and photographs. Photography and cinema have long had a complex, reciprocal yet internecinal relationship; and movie stills – which are, finally, photographs of movies – are thus an endlessly fascinating phenomenon. There is something inherently contradictory about still images of films: after all, the name of the medium in whose firmanent these stars hang is ‘moving pictures’. Films consist of a series of still images, of course, but they are shone onto the silver screen in such quick succession that the illusion of movement – even when we are consciously aware thit it is an illusion – never threatens to shatter. The images on the screen may waver, flicker, or fade; but the dream never dissolves.

On the other hand, the act of watching a film is a transitory experience. Whether we are having our senses scrambled by a jump-cut action sequence, or being seduced by the silken glamour of a black and white screen goddess languidly exhaling a funnel of cigarette smoke, the moment is always passing. Looking at a still photo of the same scene – one frame frozen out of the 24 per second torrent – what we see is both exactly the same and dramtically different. Back in the 1930s, philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin used the term ‘optical unconscious’ to describe photography’s ability to reveal what the human eye would not otherwise see, comparing photography’s effect on how we see, to the impact of psychoanalysis on what we know of our unconscious mind. Photography (as practised by pioneers such as Edweard Muybridge) opened up otherwise fleeting moments of reality to our inspection; in a sense cinema reverses this process by setting the moments in motion again. By then re-freezing that flow, and arbitrarily picking out just one still image out of the tens of thousands that make up the average feature film, are we then encountering or even creating a moment of ‘movie reality’?

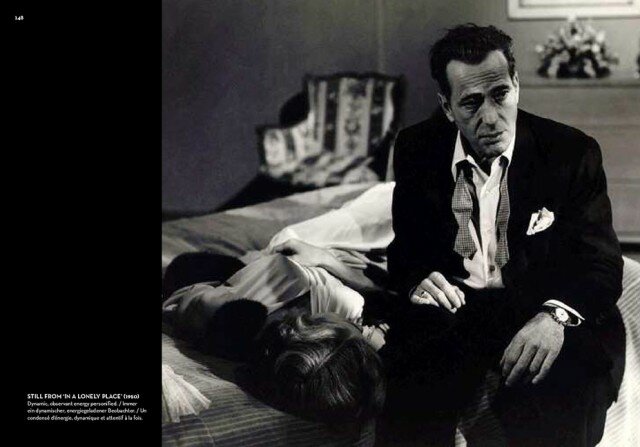

Sometimes, looking at these images, it even feels as though we are almost intruding. We have no compunction about sitting in the darkened cinema, gazing at leisure upon the features of another human being (albeit one who’s carefully made up – in both senses – costumed and coiffed, and presented – in most cases – in as flattering and sympathetic a light as possible), their face blown up to the size of a house. But they keep moving, and we have to keep following them; often, our gaze seeks to linger long after the image has gone. In these books, the still image lies naked on the page, open to prolonged, unvarying perusal. The stars are brought down to earth and pinned to the page like butterffiles. Depending on your point of view, this can be said to provide merely a harmless pleasure, or a creepy kind of accelerated voyeurism. It’s probably both.

Pondering all this, you could easily lose yourself to ontological and philosophical ruminations. Or, flicking through the pages of Taschen’s books, you could just revel in the perennial allure of movie star imagery, that always-available, never-fading glamour and glitz. And, particularly with the truly giant stars of yesteryear, we are confronted with the realisation that we do, at some level, really love these people – the Humphreys and Marilyns, the Gables and Grants.

Each entry in the Icons series throws up its own particular joys and surprises. Again and again, the reader cannot help but be brought up short by the frisson resultant from seeing an unfamiliar still from a famous scene, such as Robert DeNiro, in ‘The Godfather: Part II’, outstretched arm brandishing a cloth-wrapped gun, the muzzle-flare from which has set the cloth ablaze. You’ve seen these scenes so many times, but stopping to look at them as frozen moments can have an uncanny effect, somewhat akin to suddenly being presented with a full-colour 8×10″ glossy of something you only dreamed about.

More prosaicly, these books also serve as a reminder of just how many films these actors – ancient or modern – have made. Cary Grant, for instance, has a filmography which runs to 75 features; Woody Allen, meanwhile, has now directed an incredible 47 films. How many of those could you name? This speaks to the fact that, even for the biggest stars, the number of films for which they typically are remembered, can actually be quite small, when compared to the total volume of their output. It’s possible to be quite a committed Bogart fan, for instance, without having seen even half of his films. In the case of someone like Robert DeNiro, as you work your way through towards the back of the book, paging through the latter stages of a career, you encounter an increasing incidence of (sometimes understandably) overlooked, forgotten works. There’s a sadness to this, as there is to movie stardom in general. We think of stars as being pampered and over-paid; but in fact its they who have the rough end of the bargain: yes, the money’s usually good, but what earthly riches could we ever conceivably bestow upon them that would compensate for the gift to the world they’ve made of themselves? And just think how few big-league golden age actors you can name who had long, healthy, emotionally stable lives.

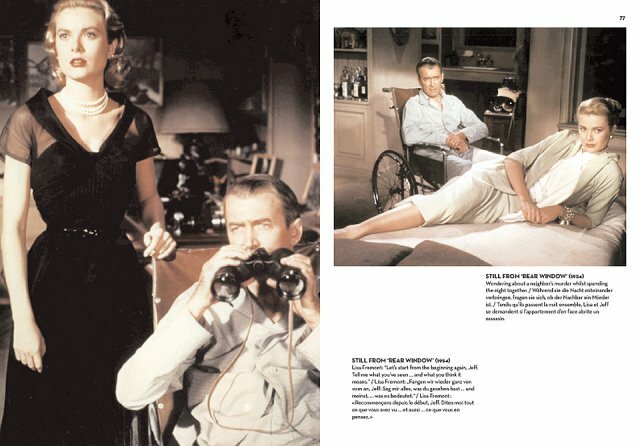

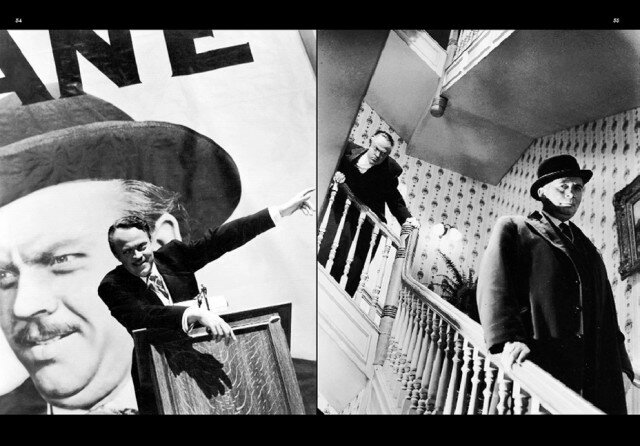

Taschen have hit upon a clever solution to the multilingual issue – each photo being captioned in a number of languages, which also applies to the generally excellent mini-essays that begin each volume. The designers make ingenious use of page layouts, often utilising facing pages to display images which are thematically and graphically consonant, as with the twin shots of Marilyn Monroe in costume and performing, or – most effectively – Orson Welles giving his triumphant electioneering speech in ‘Citizen Kane’, counterpointed with with a shot of him in disgrace, shouting down the stairs after a departing Boss Jim Gettys.

Taschen’s ‘Movie Icons’ combine high production standards with elegant design and convenient proportions. They feel good in you hand, and represent great value for money. Unreservedly recommended.

- by John Carvill

You don’t have an Icon book on Paul Newman? All your books are wonders to behold, thanks, Dave