Twenty years of schoolin’ – Dylan & Scorsese, Together Again

Who could fail to be mesmerised by the footage of Bob Dylan – legs bent, voice ragged but still powerfully expressive, silvery grey birds-nest hair blazing atop a hatless head – performing an eerily beautiful ‘Blind Willie McTell’ in “tribute to” Martin Scorsese, at the Critics’ Choice Music Awards the other night?

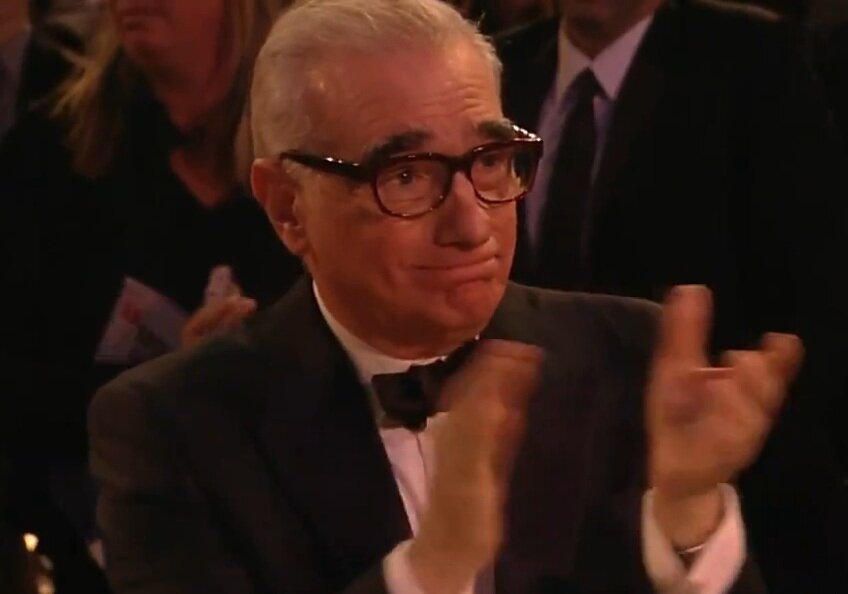

Forget for a moment the fact that Dylan gave the performance his all, or that the arrangement was (relative to what’s generally the norm these days) short and stripped back, or that the harmonica breaks were controlled and eloquent rather than blustery and fierce. No, what stood out was how apt the choice of song was for both of these great artists, whether Dylan was truly “paying tribute” or not (and Scorsese’s bemused half-grimace at the word ‘tribute’ implied he wasn’t quite accepting the term himself, perhaps subconsciously deferring to the song’s original dedicatee).

No matter, because both these great artists – acquaintances and kindreds over the years via many intertwining musical, cinematic, and cultural channels – have soared high and plunged low in critical (not to mention commercial) favour, more than once. They’ve been down, been kicked, been re-embraced and reappraised, and been seen to accept it all with a wry smile and a knowing nod.

Long before Martin Scorsese tied his tightest connection with Dylan, via 2005′s ‘No Direction Home’ documentary, he’d carried Bob’s words through their mutual old stamping ground of Greenwich Village, Dylan’s urban hipster hymn ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ donating a lyric – “Twenty years of schoolin’ and they put you on the day shift” – as the totemic epigram inscribed at the head of the shooting script for ‘Mean Streets’.

It’s impossible to know what goes through Dylan’s head when he’s on stage, whether he’s grinding through another workaday setlist on that frequently misconstrued treadmill, the ‘Never-ending Tour’ – a grave misnomer, since we know, and he knows, that it will – or blessing a celebrity audience with his award-ratifying presence. But it’s surely not too fanciful to speculate that he may well have had in mind here the fact that he and Scorsese have so much in common, not least in having both latterly been enshrined as national, or maybe planetary treasures.

Was the standing ovation that followed Leonardo DiCaprio’s post-performance shout-out of “Give it up for Bob Dylan everyone!” a tribute to Bob, or to Marty? Either way, the words Dylan sang could not have been more apposite, for both of these singular artists, each – in his own way – a blues man:

“Well, I heard that hoot owl singing

As they were taking down the tents

The stars above the barren trees

Were his only audience

Them charcoal gypsy maidens

Can strut their feathers well

But nobody can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell”

- by John Carvill

By paying tribute to Scorcese Dylan pays tribute to himself, the subject of Scorcese’s work, the work most relevant to Dylan himself – just as in Lenny Bruce he is singing about himself. As for the song Blind Willie, Dylan may not have been singing about himself in 1983 when he didn’t release it, but I might have been singing about himself the other night.

Scorcese and Dylan are wonderful

There’s a bird’s nest in Bob’s hair. Trouble in Mind:

Here comes Satan, prince of the power of the air

He’s gonna make you a law unto yourself, gonna build a bird’s nest in your hair

He’s gonna deaden your conscience ’til you worship the work of your own hands

You’ll be serving strangers in a strange, forsaken land

Dead Man, Dead Man:

Satan got you by the heel, there’s a bird’s nest in your hair

Do you have any faith at all? Do you have any love to share?