What’s Wrong With This Picture: ‘Annie Hall’ and the endless quest for the perfect Home Cinema experience.

You don’t have to be a died-in-the-wool Luddite to recognise that technology can be a two-edged sword. In fact, if you were seeking to plot a course through the last millennium or so of technological innovation, marking only those special milestones that are unanimously, uncontroversially recognised as wholly positive developments, you would end up with quite a short list, one which would probably look something like this: printing press; telescope; refrigerator; Concorde; the Draught Guinness ‘floating’ widget; rear parking sensors.

In the home cinema universe, the ‘Big Bang’ moment came with the introduction of the Video Cassette Recorder (VCR) in the late 1970s. The next big leap forward occurred when the DVD, which had gradually superseded the clunky, unglamorous VHS cassette, was combined with the widescreen TV. That vast expanse of flat, matt, glare-free screen, coupled with the crystalline clarity of DVD, allowed us to enjoy our favourite films all over again, with a richness of detail that can seem almost hallucinatory. As The Sopranos’ Paulie Walnuts poetically put it, having recently seen ‘On The Waterfront’ on a widescreen: “Karl Malden’s nose hairs looked like fuckin’ BX cables.”

But there’s always a down side. For every pro, there’s a corresponding con. Or, to put it another way, for every revelatory glimpse of Karl Malden’s nasal hair, there’s an infuriatingly unintuitive, bafflingly circuitous DVD menu system, seemingly designed by MC Escher during a bad LSD experience. (To add insult to injury, many DVDs force you to endure an excruciatingly loud jingle or dialogue snippet every time you return – however inadvertently – to the man menu screen.)

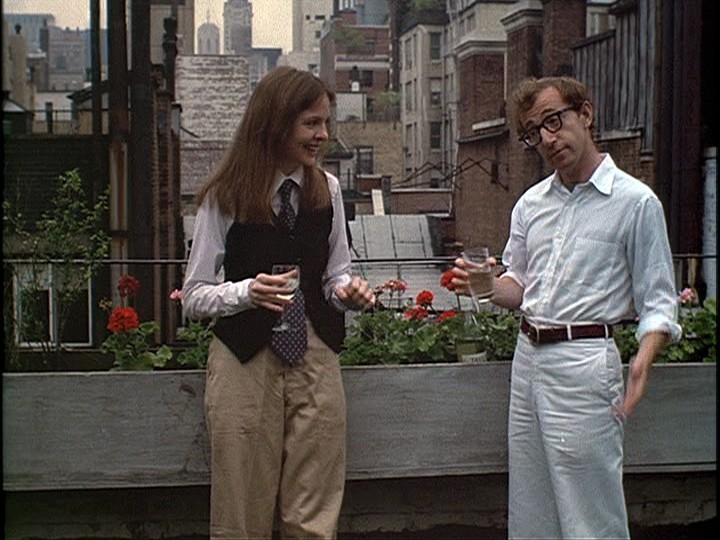

Probably the most troublesome aspect of the modern viewing experience is the vexatious matter of ‘aspect ratio’. Consider the format history of Woody Allen’s Oscar-hogging masterpiece, ‘Annie Hall’. That film was shot in a 4:3 aspect ratio, ‘matted’ to the more ‘widescreen’ 1.85:1 ratio for cinemas, and is now available on DVD in 16:9. Leaving aside the fact that 1.85:1 and 16:9 are roughly equivalent but not identical, it’s natural to regard the widescreen DVD as adhering to the ‘definitive’ format for the film. But after its cinema run ended in 1977, and prior to its release on DVD in 2000, ‘Annie Hall’ would generally have been seen only in 4:3 – via TV broadcasts and on VHS. Which means that millions of people have had key scenes from ‘Annie Hall’ indelibly imprinted upon their psyches in a 4:3 aspect ratio. So which ratio is ‘right’? When Woody sneezes that big cloud of premium quality California cocaine across the room in ‘Annie Hall’, does your mind’s eye recall that scene in ‘wide’ or ‘square’ format?

And even if you do have a firm idea of what the ideal aspect ratio for a given film is, it’s not always easy to watch it that way. Depending on the format your film was originally shot in, how your DVD version is formatted, how your DVD player is set up, and what screen format setting you select on your TV, you can often find yourself not so much spoilt for choice as overwhelmed by permutations. Adjustable aspect ratio settings mean we must constantly contend with issues such as stretching, smart zooming, errant subtitles, HDMI mode toggling, ‘letterboxing’ (horizontal black bars above and below a widescreen film image), ‘pillarboxing’ (vertical black bars either side of an older, ‘square’ formatted film image), and even the dreaded ‘windowboxing’ (both letterboxing and pillarboxing at same time). It’s all too easy to arrive at a situation whereby, no matter what sequence of available setting combinations you try, you just cannot seem to get the picture on the screen to look quite right.

Then there’s the question of DVD versioning. The ‘Region 2’ DVD of ‘Annie Hall’ offers only the 16:9 version, whereas the ‘Region 1’ disc also includes the 4:3. Both discs present a problem when it comes to the classic balcony scene, where the newly acquainted Alvy and Annie’s dialogue is hilariously contextualised by means of subtitles which reveal the characters’ inner thoughts – “Christ, I sound like FM Radio. Relax!”, etc. On the ‘Region 2’ disc, the nice, clean sans-serif font used in the original film has been replaced by rather ungainly, italicised digital text; the ‘Region 1’ version’s subtitles are rendered in a distractingly large, phenomenally ugly font, and come complete with preposterously unnecessary “[Thinking]” annotations.

Woody Allen himself is famously hands-off when it comes to curating his back catalogue. Which is ironic, given that Woody’s ’Annie Hall’ character, Alvy Singer, is depicted as being so finicky about cinemagoing that he refuses to enter a theatre two minutes after a Bergman film has started, even though as Annie (Diane Keaton) points out, “We’ll only miss the titles, they’re in Swedish.”

All these technical and artistic niggles are enough to make you pine for earlier, simpler times. In the Olden Days (circa 1995), you simply inserted a VHS cassette, waited five or six minutes for it to rewind, picture-searched (laboriously yet reliably) past a few ads, then pressed play. Maybe you gave the tracking a tweak occasionally, but that was it: your film would then play on your TV in exactly the same way every copy of that VHS would play on pretty much any other TV on Earth.

Of course, nobody is forcing us to buy into all these new technologies. Well, nobody but ourselves. Some of us can’t help it, even though – as Alvy warns us – setting up the perfect home cinema environment won’t help you escape the fact that “gradually you get old and die.” It would be fascinating to get that great media analyst (and ‘Annie Hall’ cameo player) Marshall McLuhan to comment on all this – if only we happened to have him right here today. If the medium is the message, what are today’s multimedia technologies trying to say? Probably something along the lines of “Oh God, I’ve eaten too much”, but also “I’d like some more. Feed me!”

Maybe the best way to sum up this predicament (and pass the time while we await the Blu-ray version of ‘Annie Hall’) would be to adapt the old joke about the man whose brother thinks he’s a chicken, but who doesn’t turn him in because, “I need the eggs”. At least half of the time, we realise that a new technology will likely offer as many problems as solutions; but we keep putting ourselves through it because, well, we need the eggs.

- by John Carvill

Editor’s Note: Parts of this article appeared, in a different form, in The Guardian, April 2011