A Glass of Ginger Ale with Jesus: JD Salinger’s ‘Franny and Zooey’

Part 1: A Brief Appreciation of Salinger’s Writing Career

by Michael Lee Bailey

Tenderness. I think that’s what people return to Salinger’s books for. It’s a pretty rare quality in these times of sensationalism, graphic horror, depictions of sex without love, the enshrinement of greed, and of ideology over civility, rampant naysaying, and triumphal scoffing at non-commercial values…but we all have a tender streak that’s being underserved. Salinger served it well.

His very early stories are simply good glossy magazine fare. The one that sticks in my mind is ‘The Heart of a Broken Story’, published in Esquire in 1941. It parodies the love story format by considering a possible romance between a young man and woman who meet on a bus, while making it clear that it isn’t going to happen. In a quiet way, it makes a point about possibilities in life and plays with

conventions.

Appropriately for the wartime years, he did write some morale-building things about soldiers – for instance, ‘The Hang of It’ and ‘Personal Notes of an Infantryman’ demonstrate heartfelt patriotism and commitment and a reader-friendly surprise twist at the end.

But other stories during that time consider what goes on in soldiers’ minds, and draw a distinction between patriotism and jingoism. ‘Last Day of the Last Furlough’, for instance, builds to a scene where a soldier emphatically tells a friend’s father – a WWI veteran – that his generation will not, and should not, look back with any kind of affection on their military time.

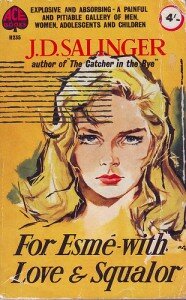

An even more moving story in this category is ‘For Esme, with Love and Squalor’, which focuses not on battlefield deeds – the only such deed mentioned is the shooting of a cat – but on a correspondence between an American soldier and a very young English girl he met on leave – and not even really so much on that correspondence as on how reading her letter relieves him from hellish desolation.

It’s exciting to watch Salinger’s talent developing in these stories, and then in the postwar stories to see him spin his themes out larger and tie them together. Notably, soldiers named Caulfield and Glass appear in the war stories, and characters with those surnames also populate the interconnected and longer tales that appeared in the 50s and 60s.

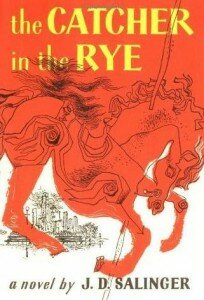

‘The Catcher in the Rye’ (1951) dealt with the tribulations of Holden Caulfield, who was of a generation too young to fight in WWII. His emotional responses to life in postwar society show a turning away from materialism and martial values in favor of the impulses of the heart.

It was a shocker for me to read even in the mid-60s, when the postwar mindset had receded quite a bit. I think it’s fair to say that in America in the 60s, boys tended to read World War II stories, spy stuff, Sherlock Holmes, Johnny Tremaine, ‘West Point Plebe’, biographies of Frank Woolworth and Thomas Edison and Lawrence of Arabia: heavily action-oriented, character-building, and devoid of existential questioning. Encountering Holden Caulfield tended to disarm one, to cut through the Social Darwinism implicit in a lot of “improving” literature. He wasn’t somebody you would emulate in order to hop on the fast track to fame and fortune, but he was much funnier and sadder, and more real, than most of those hero types.

Salinger followed the strongly emotional statement of ‘The Catcher in the Rye’ with a number of stories with a variety of viewpoints, messages and emotional inflections, many of which are loosely but compellingly interrelated by virtue of the fact that they concern members of the Glass family.

The back story is brought out gradually throughout the sequence. Les Glass, the Jewish father, and Bessie, the Irish mother, after a career in vaudeville, have raised seven offspring, all of whom were precocious young radio quiz show stars. The incidents in the stories occur after their quiz show heyday when the siblings are mostly all grown up.

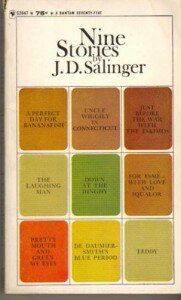

Three Glasses show up in the first collection. ‘Nine Stories’, from 1953, depicts, in ‘A Perfect Day for Bananfish’, the preternaturally (some might say, incredibly, or even intolerably) gifted and tormented eldest son, Seymour, killing himself. ‘Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut’ shows another deceased Glass sibling, Walt, through the eyes of a woman who had loved him (this was made into the movie ‘My Foolish Hear’ which Salinger disliked, but really wasn’t half bad if you ask me. The theme song is great!) ‘Down at the Dinghy’ features Boo Boo Glass, the eldest daughter and perhaps the most likeable of the bunch. The other six stories aren’t overtly Glass-ful, but they are at least Glass-compatible: especially ‘Teddy’, which explores the pitfalls of being young and freakishly gifted.

‘Franny and Zooey’ (1961) focuses on the two youngest Glass siblings, and builds the “family drama” idea up around the pain caused by Seymour’s suicide in his survivors, although it doesn’t stop there but continues on with a picture of family life, philosophical ruminations about art and the meaning of life, several belly laughs, and culminates in a very idiosyncratic Christian inspirational message.

In 1963, Salinger published ‘Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters’ and ‘Seymour: an Introduction’, two longish stories in one volume. In ‘Raise High’, the second-eldest brother, Buddy, appears in uniform on leave from the Army trying to attend the doomed Seymour’s wedding day. In ‘Seymour’, the adult Buddy, having grown (or at least, aged) into a reclusive writing instructor at a girl’s school, reminisces heartily and at rather great length about Seymour.

Finally, in 1965, further delving into the Glass family, Salinger published ‘Hapworth 16, 1924’ in the New Yorker. This long epistolary story met with some critical objections. That isn’t surprising: page after page of a letter from a seven-year-old camper, who we already know is doomed, including literary criticism and a great many precocious, prescient, and sometimes rather precious observations on most any conceivable subject, including the likelihood of his own early demise.

However, it has its fascinations!

Whether because of critical objections, his own reclusive nature, or possibly the fact that he had a decent income for life from his previous work, Salinger never published again. There’s one more story available, but you have to go to the Princeton library, show two picture IDs, and read it there in a special proctored reading room:

‘The Ocean Full of Bowling Balls’

A tale hangs thereby, certainly… not just the story, which I hope to read myself someday, but how it came to be there. Why Princeton, among other questions?

By all accounts he did keep writing and socking the stories away, but it would seem indecorous to dwell on that right now.

Among those of us who are susceptible to his sort of tenderness (and there are a lot of us! ‘Franny and Zooey’ rose to the top of the New York Times bestseller list in 1961) there is at least one who remains, without exaggeration, eternally grateful for what he did see fit to publish.

In part two, Michael will take a closer look at ‘Franny and Zooey’