You Had To Ask Me Where It Was At: Bob Dylan & the Media

An exploration of Dylan’s media relations, as refracted through Rolling Stone’s anthology of ‘essential’ Dylan interviews and press conference transcripts.

Part One: Who is Mr Jones?

“Dylan’s such a fucking maniac. Y’know, I’ve not said anything specifically, but I hope I’ve done something here to remind how intense he is, and how much that intensity has only been successfully revealed through abstract expressionism in rock’n'roll. I look at him and I don’t see a guy giving out leaflets, holding a banner. I see a machine gun.”

- Patti Smith

“I and I

In creation where one’s nature neither honors nor forgives.

I and I

One says to the other, no man sees my face and lives.”

- Bob Dylan, ‘I and I’

Bob Dylan has always been a slippery devil. In his erudite, thought-provoking introduction to this chronological collection of interviews, Jonathan Cott provides an insightful exploration of Dylan’s “particulated (some might say self-splitting) nature”, reminding us that Dylan’s ‘chameleonic’ quality was apparent right from the start of his career, when he first began hawking his boho hobo schtick around Greenwich Village. Not only did the picaresque yarns he spun about his personal history keep changing, but Dylan even seemed to be capable of radically altering his physical appearance, like “the Greek sea deity Proteus, who in order to elude his pursuers continually shape-shifted from dragon to lion to fire to flood – uttering prophecies along the way”.

The word ‘sides’ comes up a lot when talking about Bob Dylan. Dylan’s old Woodstock friend Bernard Paturel – to whom Dylan had given a loosely specified job in order to prevent Paturel from having to go and work for IBM – summed up Dylan’s omnifaceted nature better than anyone before or since, with his ineffable aphorism, “There are so many sides to Bob Dylan, he’s round.” Patti Smith recalled how certain people or situations could “bring out that ‘Don’t Look Back’ side of Dylan. Dylan’s got that side still — it’s all stored up — he’s all those people, he’s still that guy, he hasn’t turned beautiful and gentle, he’s a real bastard — but that’s what I think is great, for his art”.

One of the people who could bring out that side of Dylan was fellow folksinger (and former friend) Phil Ochs. Patti Smith recalled the night of the party before Dylan’s Rolling Thunder troupe, which Ochs had pointedly not been invited to join, took to the road: “Bob wouldn’t talk to Phil Ochs. The two of them… it was like there was a noose in the middle of the room and they were circling around, trying to get each other to hang themselves.” Tragically, Ochs actually did eventually hang himself, not long after recording a monologue in which he imagined himself confronting Dylan and telling him, “You used to be a genius, now you’re just dogshit”.

The word ‘sides’ comes up a lot even when talking to Bob Dylan. “I didn’t want to be a political moralist”, Dylan has said, “There were people who just did that. Phil Ochs focused on political things, but there are many sides to us, and I wanted to follow them all. We can feel very generous one day and very selfish the next hour.”

It’s not much of a claim to say, of any artist, that they have a number of sides; in fact it would surely be hard to find a noteworthy artist who could be thought of as one-dimensional. But the word ‘sides’, in such a context, usually means aspects; in Dylan’s case, the word more pertinently connotes ‘sides’ as in warring factions, Dylan’s personality seeming sometimes to be almost entirely composed of contradictions, dualities, and dichotomies. And it’s tempting to speculate that Dylan’s flare-ups with Phil Ochs were intensified by the fact that Ochs himself personified the side of Dylan that a lot of fans wanted Dylan to be all the time: big-hearted and decent and fired up by social conscience and political commitment.

Robert Shelton – still, even after all these years, Dylan’s most credible biographer – recorded how “Dylan’s ambivalence has confounded everyone who has ever been close to him”, and remarked how it sometimes even confused Dylan: “I’m inconsistent, even to myself.” Dylan has ascribed this to his Gemini personality, which “forces me to extremes. I’m never really balanced in the middle.”

Questions of indistinct and conflicted identity permeate Dylan’s art, at a number of levels. In an abstract sense, they manifest themselves in terms of structure – the fragmented, almost cubist approach to narrative, and the sifting of first, second, and third persons in songs such as ‘Tangled Up in Blue’, for instance. But they’re also explicitly addressed in the lyrics. Dylan pointed Shelton to the wording of ‘Where Are You Tonight?’ – “I fought with my twin, that enemy within, ’til both of us fell by the way” – citing this as a nakedly autobiographical depiction of “the mortal battle with his alter ego”, explaining to Shelton that he felt he needed to win his own inner conflicts, in order to be able to take on the world: “If you deal with the enemy within, then no enemy without can stand a chance.”

Leonard Cohen likes to tell the story of Dylan asking him how long it had taken to write ‘Hallelujah’, Cohen saying it took him “the best part of two years.” In return, Cohen asked Dylan how long ‘I and I’ had taken him to write, to which Bob replied, “Oh, 15 minutes.” The customary pinch of salt notwithstanding, there’s a level of plausibility to the claim precisely because the song seems so compellingly bound up with what we know, or think we know, about Dylan.

These dualities and inner conflicts also crop up repeatedly in Dylan’s interviews, perhaps most intriguingly when Dylan is talking to Jonathan Cott, with whom he has an obvious rapport. Cott’s probing questions often bring out Dylan’s philosophical side, leading to fascinating ruminations on dreams, the subconscious, existentialism, and the nature of the self.

Sometimes Dylan backs off:

Didn’t Dylan think that a song like “Changing of the Guards” wakens in us the images of our subconscious? Certainly, I continued, songs such as that and “No Time to Think” suggested the idea of spirits manifesting their destiny as the dramatis personae of our dreams.

Dylan wasn’t too happy with the drift of the discussion and fell silent. “I guess,” I said, “there’s no point in asking a magician how he does his tricks.”

“Exactly!” Dylan responded cheerfully.

But Cott keeps on asking:

Q. A song like “No Time to Think” sounds like it comes from a very deep dream.

A. Maybe, because we’re all dreaming, and these songs come close to getting inside that dream. It’s all a dream anyway.

Q. As in a dream, lines from one song seem to connect with lines from another For example “I couldn’t tell her what my private thoughts were/But she had some way of finding them out” in “Where Are You Tonight?” and “The captain waits above the celebration/Sending his thoughts to a beloved maid” in “Changing of the Guards.”

A. I’m the first person who’ll put it to you and the last person who’ll explain it to you. Those questions can be answered dozens of different ways, and I’m sure they’re all legitimate. Everybody sees in the mirror what he sees — no two people see the same thing.

Q. In a song such as “Like a Rolling Stone,” and now “Where Are You Tonight?” and “No Time to Think,” you seem to tear away and remove the layers of social identity — burn away the “rinds” of received reality — and bring us back to the zero state.

A: That’s right. “Stripped of all virtue as you crawl through the dirt/You can give but you cannot receive.” Well, I said it.

Q: “I’ve seen you tell people who don’t know you that some other person standing nearby is you.”

A: “Well, sure, if some old fluff ball comes wandering in looking for the real Bob Dylan, I’ll direct him down the line, but I can’t be held responsible for that.”

Of course, the trail for ‘the real Bob Dylan’ went cold decades ago. By the time Dylan was finally brought to a (temporary) halt by the locked rear wheel of his Triumph motorcycle on that lonely Woodstock road, he had left scattered behind him the husks of too many ‘Bob Dylans’ for any biographer to track. In a strikingly insightful article for ‘Cheetah’ magazine in 1967, Ellen Willis wrote that in the aftermath of the crash, the confusion surrounding what might or might not have happened “was typical. Not since Rimbaud said ‘I is another’ has an artist been so obsessed with escaping identity”. That famous Rimbaud quotation is everywhere in Dylan studies. Cott proposes it as Dylan’s ‘modus vivendi’, and it’s no coincidence that when Todd Haynes was composing a one-page synopsis seeking Dylan’s approval for his Dylan biopic-of-sorts, ‘I’m Not There’, which pirouettes around the still-disputed motorbike crash, he began with that most Dylanic of Rimbaud quotations.

Willis pointed out that “Dylan’s refusal to be known is not simply a celebrity’s ploy, but a passion which has shaped his work”, noting that “Dylan as an identifiable persona has been disappearing into his songs, which is what he wants. This terrifies his audiences. They could accept a consistent image – roving minstrel, poet of alienation, spokesman for youth – in lieu of the ‘real’ Bob Dylan. But his progressive self-annihilation cannot be contained in a game of let’s pretend, and it conjures up nightmares of madness, mutilation, death.”

No segment of Dylan’s audience was more terrified of this unidentifiability than the media. Right from the start, the tweed-jacket-sporting, briar-pipe-puffing gentlemen of the press exhibited a twitchy ambivalence about the fact that Dylan’s single most distinguishing characteristic was his disinclination to display a single distinguishing characteristic. They routinely remarked upon the astonishing fact that ‘Mr Dylan’ could not be pigeon-holed, but they often seemed determined to try anyway, throwing labels at him in the hope that they might stick. Dylan, of course, always understood that once they get you neatly packed into a box, the next step is to close the lid.

As Dylan’s early press relations took shape, he unveiled an impressive armoury of standard interview tactics: evasion, equivocation, put-ons, half-truths, and outright lies. His flamboyant displays of verbal pugnacity suggested he could have been a great trial lawyer; even more remarkable, though, was the obvious relish he took in semantic gamesmanship – warping perceived meanings, blurring the line between literal and metaphorical, questioning the meaning of questions, and indulging in bouts of disingenuity and rhetorical sophistry that would be the envy of the slipperiest politician.

He’d often alternate, with dizzying speed, between responding to a specific question with an abstract, and answering a general question with something microcosmically particular. Now and again, he’d wheel out the ultimate weapon: spooling off into Dadaist, free-associative rambles. One of this collection’s cornerstones is the inscrutably hilarious interview Dylan gave to Nat Hentoff for Playboy magazine in 1966:

PLAYBOY: Mistake or not, what made you decide to go the rock-

‘n’-roll route?

DYLAN: Carelessness. I lost my one true love. I started drinking. The first thing I know, I’m in a card game. Then I’m in a crap game. I wake up in a pool hall. Then this big Mexican lady drags me off the table, takes me to Philadelphia. She leaves me alone in her house, and it burns down. I wind up in Phoenix. I get a job as a Chinaman. I start working in a dime store, and move in with a 13- year-old girl. Then this big Mexican lady from Philadelphia comes in and burns the house down. I go down to Dallas. I get a job as a “before” in a Charles Atlas “before and after” ad. I move in with a delivery boy who can cook fantastic chili and hot dogs. Then this 13-year-old girl from Phoenix comes and burns the house down. The delivery boy – he ain’t so mild: He gives her the knife, and the next thing I know I’m in Omaha. It’s so cold there, by this time I’m robbing my own bicycles and frying my own fish. I stumble onto some luck and get a job as a carburetor out at the hot-rod races every Thursday night. I move in with a high school teacher who also does a little plumbing on the side, who ain’t much to look at, but who’s built a special kind of refrigerator that can turn newspaper into lettuce. Everything’s going good until that delivery boy shows up and tries to knife me. Needless to say, he burned the house down, and I hit the road. The first guy that picked me up asked me if I wanted to be a star. What could I say?

PLAYBOY: And that’s how you became a rock-’n'-roll singer?

DYLAN: No, that’s how I got tuberculosis.

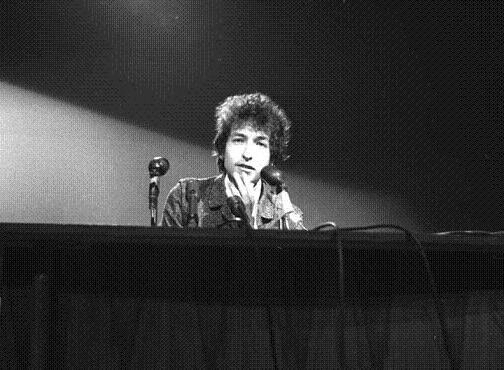

It might be tempting to nominate the Playboy interview for the coveted title of ‘quintessential 1960s Dylan press encounter’; but that honour surely should go to the transcript of the televised KQED San Francisco press conference from 1965. Dylan was in San Francisco to play a short (but spectacular) series of concerts, and had agreed to fly in a day early in order to appear at the press conference which Rolling Stone co-founder Ralph J Gleason had arranged for KQED-TV to broadcast live. Only six months or so after his infamous schism-generating electric performance at Newport, the 24 year old Dylan was beginning to take his final steps away from any semblance of a naturalistic interview persona. Dylan and the media, at that stage, were probably just about equally bemused by each other; throughout the conference, he and the assembled press circle each other like incompatible yet equally haughty families whose children have recently announced their shock engagement.

Many TV viewers were no doubt taken aback by Dylan’s behaviour when it was broadcast, but what seems most striking in retrospect is how the reporters behaved towards Dylan, treating him like a talking dog, or an alien recently beamed down to earth. In retrospect, this seems utterly bizarre, unless you read the transcript as documenting a set of modulating cultural forces. Like someone standing on the headland of the Skagen penninsula in Denmark, watching the crashing together of waves from two opposing seas, attendees of the press conference could witness countervailing historical currents swirling around on the surface of time. This wasn’t a simple case of ‘Dylan meets the Press’ – this was the end of an era.

It’s hard to select a favourite quotation from the KQED transcript, but in terms of its most representative moment, you’d be hard-pressed to pick anything better that this:

Q: “Mr Dylan, I know you dislike labels and probably rightfully so, but for those of us well over thirty, could you label yourself and perhaps tell us what your role is?”

A: “Well, I’d sort of label myself as ‘well under thirty’. And my role is to just, y’know, to just stay here as long as I can.”

This sort of exchange, as well as providing everybody present with a good laugh, became emblematic of the rapidly widening generational gap between those who were determined to prolong an earlier era, and those who were in the process of burying it. Dylan was writing the soundtrack to these historical changes, live, as they were happening; and that soundtrack was, in turn, coiling around on history and altering its course, accelerating its forward momentum, away from anything that mainstream American society could embrace, tolerate, or even recognise.

The nonconformist outlook reflected in Dylan’s early lyrics, coupled with his relentlessly irreverent demeanour, delivered a colossal thunderbolt of culture-shock to a mainstream media, and an American society, still heavily mired in the straight-laced, rigidly conservative mindset of the 1950′s. The stultifying inertia of the 50s was perfectly captured by novelist Thomas Pynchon – one of the very few countercultural figures with an even more prickly and pessimistic attitude to the press than Dylan – in the introduction to his short story collection ‘Slow Learner’:

“One year of those times was much like another. One of the most pernicious effects of the 50′s was to convince the people growing up during them that it would last forever. Until John Kennedy, then perceived as a congressional upstart with a strange haircut, began to get some attention, there was a lot of aimlessness going around.”

Depending on which side of that socio-cultural divide you were standing, Dylan could seem either dangerous or endangered, threatening or fragile, something like the James Dean and Marlon Brando figures he had idolised and identified with in his Minnesota youth. Pynchon and Dylan’s mutual friend Richard Farina – writer, singer, and husband to Joan Baez’s alluring younger sister Mimi – summed up this sense of vulnerability in an article for ‘Mademoiselle’ magazine in 1964, when he depicted a Berkeley concert audience anxiously awaiting Dylan’s arrival:

“They seemed, occasionally, to believe he might not actually come, that some malevolent force or organization would get in the way.” Not content with burning the candle at both ends, Dylan was “using a blowtorch on the middle,” and might not be around too much longer. “Catch him now, was the idea. Tomorrow he might be mangled on a motorcycle.”

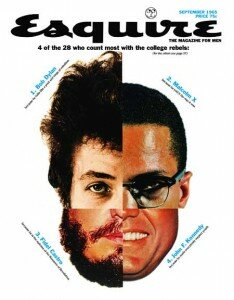

At the KQED press conference, Dylan is asked what he thinks about Phil Ochs’s statement in a recent ‘Broadside’ magazine article, that “you have twisted so many people’s wigs that he feels it becomes increasingly dangerous for you to perform in public,” and Farina quotes Robert Shelton as warning that Dylan is “a moving target, and he’ll fascinate the people who try to shoot him down.” In the wake of the Kennedy assassination, which ramped up the paranoia levels of anyone already susceptible, Pynchon and Dylan included, Esquire magazine’s 1965 magazine cover – featuring an image of a hybrid human head, constructed using a quarter each of the faces of JFK, Malcolm X, Fidel Castro, and Bob Dylan. Cheekily suggesting the crosshairs of a sniper rifle, the image only served to reinforce the idea that someone might literally shoot Dylan.

In any case, plenty of media figures were certainly out to metaphorically gun Dylan down. If press profiles of the 1960′s tended to alternate between two reductively extreme views of Dylan – he was either a prophet or a phoney – then Newsweek’s vicious 1963 ‘expose’ was definitely in the latter category. Newsweek gloatingly revealed that Dylan wasn’t the orphaned boxcar-rider he’d made out, but was, in shocking fact, a nice middle-class Midwestern Jewish boy named Zimmerman. Ridiculing Dylan’s lyrics as “simple words that pounce upon the obvious,” the article also implied that Dylan had not even written those simple words, gleefully repeating long-discredited rumours that he had purchased the lyrics to ‘Blowin in the Wind’ from a college classmate. On first reading the Newsweek article, Dylan reportedly exclaimed, “Man, they’re out to kill me!”

Dylan made his incendiary anger about this sort of thing explicit in a number of ways, from the reference to “the dirt of gossip” in ‘Restless Farewell’, to the dismissal of the media in ’11 outlined Epitaphs’: “your questions’re ridiculous, an’ most of your magizines’re also ridiculous”. And the side of Dylan Patti Smith was referring to – caustic, rebarbative, and snide – was on full display in a scene which became, for many, the defining image of the Dylan interview experience: the harangue he unleashes on hapless Time Magazine reporter Horace Judson in DA Pennebaker’s cinema verite masterpiece, ‘Don’t Look back’. Like the heads on spikes once displayed on the Gate House of London Bridge as a warning to other criminals, Dylan’s casual, even gratuitous evisceration of the ‘Time’ magazine stringer casts a baleful shadow over all subsequent press encounters.

It’s often seen as simply an ill-tempered rant, Dylan barely managing to keep a grip on himself as he informs the astonished hack that truth is “…a plain picture of, let’s say, a tramp vomiting, man, into the sewer”, and you can almost see the hair on Judson’s head being blown back by the gale force of Dylan’s vituperative outburst. But looked at dispassionately, behind the surreal vitriol there’s more than a grain of truth to what Dylan says, and who can argue with his assessment of the tenuous relationship between ‘Time’ magazine and the truth:

“If I want to find out anything I’m not going to read ‘Time’ magazine. I’m not gonna read ‘Newsweek’. I’m not gonna read any of these magazines, I mean, ’cause they just got too much to lose by printing the truth, you know that.”

That “you know that” is crucial. Pre-eminent Dylan critic Michael Gray has suggested, quite reasonably, that Dylan’s reaction to Judson is “in context, restrained,” and praised Dylan’s “earnest honesty”, asserting that Dylan’s treatment of Judson went “beyond dismissal and became a reaching out to the person inside the journalist: became Dylan trying to teach them something true.” Which would amount to a remarkable act of spiritual generosity on Dylan’s part, given that ‘Time’ had once described him as “a dime-store philosopher, a drugstore cowboy, a men’s room conversationalist”, and “the newest hero of an art which has made a fetish out of authenticity”. As if authenticity ought to be something for artists to shy away from.

If Dylan very quickly developed a skittish, mistrustful attitude to the media, albeit one tempered by the inevitable Dylan ambivalence, the press were even more suspicious and conflicted about him. It was painfully ironic that, in so spectacularly failing to understand him, the press often exhibited a bipolar attitude to Dylan, which in a sense mirrored Dylan’s own propensity for flipping from one extreme to another. The media seemed torrn between being awed by Dylan and condescending towards him; they mocked the idea that Dylan might have anything worthwhile to say, yet they expected him, even in casual conversation, to spontaneously Oraculate; and they were often convinced that there must be even more to Dylan than met their uncomprehending eye, some ‘philosophy’ or ‘meaning’ over and above what was presented to them on the surface. They didn’t know what to make of him, basically, and panic set in.

Thomas Pynchon recalled a similar sense of panic, suffered by those caught on the wrong side of the cultural ‘transition point’ which marked the arrival of Elvis Presley, who, prior to Dylan, had seemed the most alien and inexplicable figure ever to have coalesced out of the cultural ether: “‘What’s his message?’ they’d interrogate anxiously, ‘What does he want?’” The idea that Dylan must have some sort of ‘message’ was one on which the press seemed ineluctably fixated during the 1960s, and it’s significant that Dylan lays such disdainful emphasis on the ‘M’ word when he tells Horace Judson, “there’s no great ‘message’”.

The lines between Dylan the artist, and Dylan the interviewee, began to blur. To claim that Dylan revolutionised the ‘art’ of the celebrity interview in the same way as he tore apart the conventions of popular song craft, might be too simplistic a view to bear much analysis; but there’s no denying that Dylan turned his press encounters into acts of surreal performance art. This cut both ways: once Dylan began to be engulfed in fame and music industry machinations, Dylan the interviewee began to influence Dylan the artist, a process which reached its apotheosis when Dylan began including, in his songs, commentaries on fame and the other ostensibly unwelcome accoutrements of his success.

His mockery of the media and their quixotic quests for hidden meanings culminated in ‘Ballad of a Thin Man’, in which Dylan distilled the essence of his every negative media experience into one of his most exquisite character sketches, the perennially baffled figure of ‘Mr Jones’, whose name would forever stand as a metonym for journalistic cluelessness.

As if to prove Dylan’s point for him, every now and then a reporter would actually ask him right out, “Who is Mr Jones?” But for all Dylan’s legendary froideur towards pressmen and their inanities, he never has had the heart to give them the obvious, brutally truthful answer: “Ask not for whom ‘Mr Jones’ was written, my journalist friend; he was written for thee.”

>> Go to Part Two: Poets Drown in Lakes

WOW John this is the best article I have read about Bob & the press,when I started to read it I thought “here we go again” but I was extremely wrong ,havn’t got more to say at the moment as I must read it again & let it sink in ! well done , great stuff !!

Yeah, this was interesting as hell..the comments about the Judson interview will stick with me the most. Thanks much!

[...] I’d like to draw your attention to a fine, thoughtful article by John Carvill that has just appeared online. ‘You Had To Ask Me Where It Was At: Dylan & the Media’ (Part 1) is here on Oomska. [...]

“prior to Dylan, [Elvis] seemed the most alien and inexplicable figure ever to have coalesced out of the cultural ether”. Possibly, although Dylan’s interviews need also to be seen in the context of the Beatles’ interviews on their 1964 US visit, which set the bar for evasion, wit and wordplay. The atmosphere at those Beatles interviews may seem relaxed and cheerful, but it would be a mistake to forget that the press, which tended to reflect a mainstream perspective, saw something deeply alien in them. They may not have had the political edge that concerned some commentators about Dylan, but from a cultural point of view they posed at least as much of a threat. From where we sit now, it may seem absurd and inexplicable, but in a culture that prized conformism more than almost anything, some people felt nothing short of rage at the fact that the Beatles’ hair came an inch or so over their ears.

Thanks very much to everyone for the comments.

It was particularly gratifying to get a nod from none other than Michael Gray himself.

@wee tommy: You’re absolutely right about the Beatles and their relationship with the press in the United States, and their revolutionary impact. I touched on that very subject in a write-up of Ian MacDonald’s great Beatles book ‘Revolution in the Head’, for popmatters, last year:

http://www.popmatters.com/pm/feature/115775-revolution-in-my-head-the-beatles-records-and-the-sixties-by-ian-mac/

To be fair, though, by the time the Beatles started making an impact on the US media, Bob Dylan had already ‘coalesced out of the cultural ether’, so even if you view the Beatles as more alien-seeming (to the mainstream), Bob beat them to it, I’d say!

Cheers

John Carvill

Excellent article, well done.

It’d be nice to see something in-depth about Dylan’s impact on the Beatles. Much has been made about his “turning them on” and also about the Beach Boys’ “Pet Sounds” influencing Sgt Pepper. I’ve always heard echoes of “Highway 61 Revisited” in Sgt Pepper.

Great idea, Joe. Go ahead!

Would particularly like to read something on Highway 61′s influence on Sgt. Pepper.

Right on Joe….I would love to read an article like that too

[...] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Craig Danuloff. Craig Danuloff said: Spectacular article(s) on Dylan & The Press – http://clck.it/bb2u4D – "There’s enough of everything. You name it, there’s enough of it." [...]

[...] Part I, Part II and Part III + tags: dylan / music Gloom → [...]

[...] << Back to Part One: Who is Mr Jones? Share this:FacebookEmailStumbleUponDigg This entry was posted in Music and tagged Bob Dylan, John Carvill, Rolling Stone. [...]