‘You Never Give Me Your Money: The Battle for the Soul of The Beatles’

by Peter Doggett. Published by The Bodley Head Ltd; 400pp; £18.99

by John Carvill

Do we really need another Beatles book? There must be, what, hundreds of them by now, right? Actually, the tally isn’t that vague, because last year, what the world was waiting for was finally published: a book about Beatles books. The elaborately named W. Fraser Sandercombe’s indispensible compendium, ‘Beatle Books: From Genesis to Revolution’, lists over 1,400 books about the Beatles; and of course, that total is now out of date.

Do we really need another Beatles book? There must be, what, hundreds of them by now, right? Actually, the tally isn’t that vague, because last year, what the world was waiting for was finally published: a book about Beatles books. The elaborately named W. Fraser Sandercombe’s indispensible compendium, ‘Beatle Books: From Genesis to Revolution’, lists over 1,400 books about the Beatles; and of course, that total is now out of date.

Despite this apparent superfluity, however, a more useful question would be: is there anything more to be said about the Beatles? The answer to that one is, unquestionably, yes. For one thing, the vast majority of Beatles books cover the same old ground, sometimes inaccurately, often superficially, and almost always with a total absence of the sort of passion, personality, and verve which so enlivened the Beatles’ music.

Another factor is the tendency of many Beatles biographies to sort of peter out towards the end of the group’s recording career, leaving the messy and summary-defying subject of their breakup relatively undocumented. Bucking this trend, Peter Doggett starts his story at roughly the point most Beatles books begin to tail off. Although the book’s title implies that it focuses solely on the convoluted and contentious business relationships that helped to break the group up, a more accurate (if less poetic) title might be, ‘The Beatles: What Happened Next’.

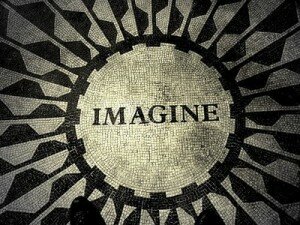

After a brief prologue, in which he employs an almost cinematically vivid style to describe Lennon’s murder at the pudgy hands of Mark David Chapman, Doggett’s savvy, tightly controlled narrative follows the Beatles from their Sgt. Pepper peak as “princes of pop culture”, through the edifice-rupturing death of Brian Epstein, their last days at Abbey Road, the “agonising corrosion of 1969”, chequered solo careers, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductions, the Anthology series, and so on; all the way up to the recent, long-anticipated release of their remastered CDs.

The story is rich in ironies. Although Apple Corps, the Beatles’ overall holding company, had been dreamt up as a way of avoiding tax, it quickly “became a sketch for utopia”, offering what Paul McCartney described as a kind of “Western Communism”. But this very soon warped into a “corporate prison which would sap their vitality and their willingness to survive, and prove to be inescapable long after the utopian fantasies had been forgotten.”

The Beatles issued an open invitation to any artists who wished to have their work released under the Apple banner, and somehow, incredibly, failed to anticipate the inevitable deluge which resulted. While hundreds of unopened demo tapes piled up in a dusty storeroom, urbane Beatles PR guru Derek Taylor presided over a culture which was more cannabanoid than corporate, a freewheeling enterprise whose cogs were oiled with plentiful inebriants.

Doggett quotes Taylor himself: “The weirdness was not controlled at the start. You can’t control weirdness, anyway; weirdness is weirdness.” Visitors to Taylor’s office could not realistically expect to transact anything resembling the conventional notion of ‘business’, but they could always be confident of a ready supply of “the finest dope and whisky”. One publisher remembers a meeting with Taylor:

“The entire room was a haze of cannabis. It was ridiculous – you could hardly breathe. I asked Derek for some new photos of the Beatles, and he wandered around the room in a daze, and eventually gave me some – which turned out to be the same ones I’d given them. But that was what Apple was like.”

Haemorrhaging money at a phenomenal rate, Apple also saw its salubrious premises become a sort of way station for a variety of not-quite-desirable passers-through. Anyone who seemed to have ‘the right vibe’ was welcomed like a long lost brother. Now and then, the office would even suffer a full-on invasion of Hells Angels or, worse still, the Hare Krishnas.

Subsidiaries and sub-divisions began sprouting like mushrooms, until there were as many as 33 distinct companies “sheltered under the Apple umbrella”. Always the shrewdest Beatle, Paul McCartney was the first to realise that he was now “part-owner of an organisation that wasn’t organised”, but by that stage, there wasn’t much he could do about it. Not only that, but McCartney himself was not immune to Apple’s prevailing culture of insouciant largesse. Mal Evans, the Beatles’ gentle giant of a road manager, describes a typical Apple board meeting:

“We had a meeting to set up Apple, and we were all sitting round this big table eating sandwiches and drinking. Paul turns round to me and says, ‘What are you doing these days, Mal, while we’re not working?’ ‘Not too much, Paul.’ He says, ‘Well, now you’re president of Apple Records.’ Thank you very much!”

Another painful irony was that the Beatles had envisaged Apple as a way of allowing artists to focus on art, without worrying about business matters; but they soon found that their endless business and legal entanglements prevented them from focusing on being Beatles. During the band’s final months together, as their byzantine legal disputes and escalating interpersonal recriminations began to strangle their creativity, the happy hippy veneer struggled to conceal the much less groovy reality underneath.

There was much unpleasantness. Yoko Ono became the spectre at the Beatles’ feast, omnipresent and universally despised. Whatever your view of Yoko Ono, it’s sobering to reflect on just how much racist abuse she was subjected to, in the middle of the supposedly love-drenched Sixties, by Beatles fans and by the band themselves. At one point, McCartney sent Lennon a typewritten note which read, “You and your Jap tart think you’re hot shit.”

Probably the heaviest irony of all is the incongruity between the Beatles’ late-period peace and love anthems, and the wars of attrition they were waging on each other at the time. In between recording “conciliatory ballads” such as ‘Hey Jude’ and ‘Let it Be’, the Beatles were more likely to be focused on court cases than chord changes. Conversely, in the midst of some of their most rancorous disputes, they occasionally managed to set aside their differences, as when “Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison were able to devote almost twelve hours to recording the most choirboy-perfect harmonies of their entire career, on Lennon’s composition, ‘Because’.”

The group’s numerous legal hassles stretched on for years and years, turning the Beatles into the Jarndyce & Jarndyce of Rock n Roll. There were law suits between Beatles, between the Beatles, Apple and EMI, and, later, between Apple Corp and Apple Computer; but the most impactful legal disputes related to Allen Klein, the tough-talking American manager of the Rolling Stones, who had set his sights on managing the Beatles and, with Epstein dead, finally found them vulnerable enough to succumb to his unctuous advances.

Championed by Lennon – with whom Klein had bonded by cannily playing up his ‘working class’ credentials, as well as the fact that, like Lennon, he had lost his mother at an early age – Klein gradually won over all the Beatles except McCartney, who wanted his soon-to-be father-in-law, Lee Eastman, to manage their business affairs. This schism became a major factor in the demise of the group. Ultimately, Klein ‘got’ the Beatles, but they would not continue being ‘The Beatles’ for much longer. “As Apple aide Tony Bramwell noted, ‘Allen Klein had achieved his ambition of managing the Beatles, but in so doing, he blew them apart.’”

Klein, who Derek Taylor described as having “all the charm of a broken lavatory seat”, is usually depicted as a grotesque, thuggish figure, a cross between Richard Nixon and Al Capone. But Doggett seems unusually equivocal on the matter, de-emphasising Klein’s more negative aspects, and pointing out the deals Klein brokered which benefited the Beatles (and himself) financially. If Klein was really so bad, Doggett asks, why would three quarters of the Beatles trust him? Well, perhaps they weren’t seeing clearly at the time.

Brian Epstein had had his faults, but he was honest, well-intentioned, and regarded the Beatles as family. He had relieved them of all manner of commercial considerations, and acted as an essential ‘buffer’ between John and Paul. Essentially, Epstein had insulated them from reality. After his death, the Beatles resembled “closeted princes faced with a high-street vending machine”. They could often be simultaneously innocent and cunning. Harrison and Lennon seem to have been particularly naïve about money (not something usually said about the pecuniarily sensitive Harrison). Prone to “imagining that they operated in some magical dimension where their actions had no consequences”, they were able to “maintain their friendship with Klein and simultaneously work for his overthrow – a talent for duplicity that might have brought them success in Caesar’s Rome.” Even when they were engaged in a series of legal battles with Klein, they used him as a sort of human cash-point, tapping him for a loan any time they needed a chunk of ready cash – often so they could ‘lend’ it to an impoverished friend. At one point, Harrison and Lennon, between them, owed Klein nearly $500,000 in cash. Lennon’s mismanagement of his own money meant that when he and Yoko came to purchase their apartment in New York’s Dakota building, he had to raise funds by selling his Ascot mansion, Tittenhurst Park, to Ringo.

Over the years, Klein and the Beatles fired volleys of law suits at each other in much the same way that rival Chicago gangsters used to exchange bursts of gunfire. There were sufficient numbers of legal actions, on both sides of the Atlantic, to keep five law firms in full-time work. At one stage, the Beatles received a much-needed influx of cash, due to the spectacular success of the so-called ‘Red’ and ‘Blue’ compilation albums. These collections had been conceived, and compiled, by Allen Klein, yet their success provided the funds for the Beatles to continue pursuing him through the courts.

Doggett does an admirable job of making a detailed description of business and legal intricacies seem reasonably interesting, but after a while it can get a bit wearying in its relentlessness. If reading about this threatens to be a slog, we can only imagine what it must have been like to live through. The situation was so bad at one stage, says Doggett , that “none of the four Beatles could go out in public without the risk of being served with a writ.”

Often, it was the little niggling details which caused the most damage. At a crucial juncture in Klein’s battle to gain control of the Beatles, with McCartney still lobbying hard for the job to go to Lee Eastman, the more gentlemanly Eastman sent his son, John Eastman, along to a meeting, calculating that the Beatles might respond better to someone younger and less stuffy. Naturally, Lennon took this as an unforgivable act of haughty disdain on Eastman’s part. And Lennon’s famous refusal to “be fucked around by men in suits sitting on their fat arses in the City”, led directly to the collapse of negotiations which might have prevented the Beatles’ song-writing catalogue passing out of their ownership, a situation that persists to this day.

Finally, almost a decade after Epstein’s death had paved the way for Klein to enter the Beatles’ lives, their long-simmering feud came to a head. Lennon, Harrison, and Klein were due to attend a High Court hearing in London in January 1977. McCartney wasn’t involved, because he had refused to sign the management contracts under dispute, and Ringo had escaped because he was spending that year in tax exile. Harrison and Lennon dreaded the court appearance. “It’s going to be awful if it does come to court,” said Harrison, “a fiasco and a nightmare, because it’s going to be open to the public and the press.” Lennon, by that stage having moved to New York, was reluctant to return to Britain under such unedifying circumstances. He had always imagined any homecoming to be “a scene of triumph mixed with sweet nostalgia.” With neither man having the stomach for it, they called upon the services of “an unlikely saviour: Yoko Ono.”

After a weekend’s negotiations between Ono and Klein at the Plaza hotel in New York, an agreement was reached whereby Klein would relinquish all claim to any involvement with the Beatles, with all outstanding grievances now being considered settled, for a one-off payment, to Klein, of just over $5 million. With characteristic flamboyance, Klein issued a statement in which he praised “the tireless efforts and Kissinger-like negotiating brilliance of Yoko Ono.” Klein’s five million came “from the collective Apple pot earned by the four Beatles up to September 1974”. If this did not sit well with Paul McCartney – since he had done everything possible to avoid getting involved with Klein in the first place – neither did the subsequent revelation that Lennon and Ono had based their decisions on when and how to negotiate, on Tarot card readings.

Out of the frying pan, into the fire: in 1978, not long after the Beatles’ “seemingly endless” struggle to shake themselves free of Allen Klein had finally succeeded, “Apple managing director Neil Aspinall learned that a young computer company in California were using the Apple name and a fruity logo.” The resultant legal dispute lasted even longer than the battle with Klein, eventually being resolved in an out –of-court settlement in 2007:

“Apple Corps agreed to cede ownership of all the Apple trademarks to Apple Computer, who in return would license the relevant names back to the Beatles’ company. Forty years after it was founded and launched as an alternative to the capitalist system, Apple Corps now only existed by permission of a corporation – which, it could be argued, had kept closer to the Beatles’ original philosophy than the group had done themselves.”

Quite how it could be argued that Apple Computer adheres (or even aspires) to some sort of hippy idealism, Doggett does not explain. Another oddity is his speculation that Paul McCartney must have witnessed Beatles biographer Philip Norman declaring, on US breakfast TV, that “John Lennon was the Beatles” – otherwise, McCartney’s loathing for Norman’s book, ‘Shout! The True Story of the Beatles’, is “unfathomable”. This despite the fact that ‘Shout!’ is so unmistakably biased in favour of Lennon. Stranger still is Doggett’s defence of McCartney’s attempts to have his and Lennon’s song-writing credits changed from ‘Lennon/McCartney’ to ‘McCartney/Lennon’.

Most striking of all, however, is Doggett’s treatment of Alexis Mardas, the Greek electronics ‘expert’ known to all as ‘Magic Alex’. If Doggett is ambivalent on Allen Klein, he seems to be mounting a concerted campaign to rehabilitate the rather tattered reputation of Magic Alex. Doggett accurately states that Alex is “often dismissed” as “a ‘television repairman’ of no technical ability”, but also claims that Alex was “recognised as a scientific prodigy as a teenager”, and seems to feel that he has been unfairly maligned. Alex’s technical skills were put to the test when he was contracted to build a ‘state of the art’ recording studio for the Beatles, in the basement of Apple’s Savile Row headquarters. The result was declared unworkable by George Martin and his EMI engineers. George Harrison called it “the biggest disaster of all time”. Alex’s studio had to be ripped out, and replaced with equipment from EMI. According to Doggett, however, Alex now claims that the studio which was so mocked at the time was only a prototype, and that it had been transferred from Alex’s workshop to Savile Row before it was ready. What’s odd is that Doggett appears to be giving equal weight to the versions of this story presented by George Martin and Magic Alex, saying that “Whatever the truth, portable recording equipment had to be ordered and installed”. But Alex’s account of the matter is based on the assertion that “someone from Apple or EMI broke into his Apple Electronics workshop and transported his work-in-progress to the Savile Row basement”. How could any credence possibly be given to such a claim?

On the other hand, the fact that matters such as these continue to be disputed and debated, points up another reason why books like this are still needed: the exact details of why the Beatles split have yet to be conclusively established. Klein was a big factor, as was Yoko Ono’s irreversible penetration of the Beatles’ inner circle; but if there was a ‘battle for the soul of the Beatles’, then that battle was fought between the four Beatles themselves. Despite their talent, acclaim, and success, each man suffered mightily from his own set of seemingly ineradicable insecurities. This led to a highly complex dynamic within what Doggett calls the group’s “delicate internal framework”, leading to its collapse when exposed, after Epstein’s death, to external pressures.

Many bands go on for far longer than they should, sputtering to a halt and leaving a trail of increasingly lacklustre albums in their wake. When the Beatles split, they still had plenty of creative fuel left in their tank, and there’s no doubt that, had they continued, the world would now have dozens more Beatles songs to revel in. Looking back on the final days, Paul McCartney reflected that, whatever the downsides, at least the Beatles had stayed true to their intention to “always leave them laughing”.

Even at the time of Lennon’s murder in 1980, the group were still “caught in a claustrophobic web of financial obligations”, and – at least in terms of their continuing business dealings – Yoko Ono effectively became a member of the group whose break-up she is often accused of causing. Ono’s “elevation to ersatz Beatle status presented a baffling conundrum to Lennon’s former colleagues”. As the years have gone by, Yoko’s power has increased significantly, to the extent that Paul McCartney worries what may happen to his legacy if the “seemingly indestructible” Yoko outlives him and goes on, “guiding the Beatles deep into the 21st Century.”

This is an elegantly constructed, well-written and – yes – necessary book. Doggett is clearly a Beatles fan (and confirms this in an afterword), yet he doesn’t take sides, and there are large swathes of the narrative in which nothing positive is said about the flawed individuals who came together to form the perfect pop group. The story of the four men who brought such pleasure to many millions is often tinged with deep sadness.

Dhani Harrison said, “people never got over the Beatles”, which is true. But then neither did the Beatles. Although no individual Beatle’s post-Beatles career was entirely without merit, nothing any of them did could ever hope to measure up to what they achieved together. While the world continued to wait for the Beatles reunion that would surely come one day, the individual members of the band did their best to establish themselves as separate artistic entities, people for whom ‘The Beatles’ was just one of things they did, long ago.

John Lennon was the Beatle who displayed the most tenacious determination to out-run his own shadow, trying to convince us (and himself) that he didn’t ‘believe in Beatles’ any more. His infamous 1970 Rolling Stone interview with Jann Wenner was, says Doggett, his “last great piece of concept art”. It “delivered the death knell for the whole fantasy that would become known as the Sixties.”

“Being a Beatle nearly cost me my life”, Lennon wrote, in a diary entry which was published by Yoko, after his death. If he’d said that while he was still alive, it would have sounded melodramatic. But of course, it now seems eerily prophetic.

“The dream’s over”, Lennon told Jann Wenner, “and I have personally got to get down to so-called reality.” Instead, so-called reality caught up with John Lennon – and, by extension, with the Beatles – outside the Dakota building in New York, in December 1980. Doggett reserves some of his most finely balanced prose for the description of this, the moment when the dream really did end:

“As he neared the cubicle where the night guard was sitting, a voice called from the shadows: ‘Mr Lennon?’ Then there was only a barrage of noise that echoed through his head. He stumbled forward a few paces, out of the instinct to survive, and fell to the ground. A torrent of blood, fragments of bone and fleshy tissues surged in his chest and was propelled out of his mouth, and oozed from the wounds torn in his torso and neck. His face was grotesquely squashed against the floor. There was a gurgle, which might have been a word lost in the ebb of his life force, and slowly his body rolled onto its side, having served its final purpose. Then the scene reels away, as if in horror, to a world from which John Lennon would always be absent.”

it is a wonderful article, i like it, thank you very much!

Great review but both yourself and Doggett are old-school believers in ‘rock journalism’ tropes which will die when you do, because the transfer to current generations is highly unlikely to succeed (no matter how hard the music mags try to pretend they have influence upon youth now).

I’m talking about transparent baggage like ‘nothing any of them did could ever hope to measure up to what they achieved together.’

Yes and I’ll never forget my first job. It was me at my peak.

F that shirt.

Doggett’s book is and was so welcome in that it took a fairly anti-judgemental at some factualities (sic) that take place after all the luvvie biographers like Philip ‘Daily Twunt’ Normal have done their best to pretend that Apple died in humiliation for all time in 1970 for not being a proper investment.

His treatment of McCartney is neither condescending or approving which helps to get us into a ‘real’ narrative where John is not The Beatles because his mummy’s dead.

It’s a start but only a start.

As Doggett laments, someone like me getting in on the game at this late stage of literacy is doubtful but if and when I do, I can DO this.

[...] ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’ was the first book ever reviewed here on oomska. You can read our thoughts on it here: ‘You Never Give Me Your Money: The Battle for the Soul of The Beatles’ [...]